linguists

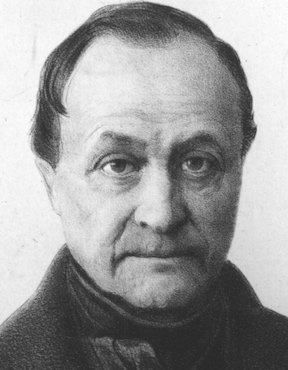

Auguste Comte

On this date in 1798, Auguste Comte, the founder of positivism and generally considered the father of sociology, was born in Montpellier, France. A mathematical prodigy, he rejected belief in God by age 14. He gave a series of lectures on positive philosophy in 1826, which were eventually published. Positivism is defined as a theory stating that certain (“positive”) knowledge is based on natural phenomena and their properties and relations. Thus, information derived from sensory experience, interpreted through reason and logic, is the source of much knowledge.

He married Caroline Massin in 1825. “The Course of Positive Philosophy” (“Cours de Philosophie Positive”) was a series of texts he wrote between 1830 and 1842. The works were translated into English by Harriet Martineau and abridged to form The Positive Philosophy of Auguste Comte, published in 1853. He was a close friend of John Stuart Mill.

In the 1840s he developed Religion de l’Humanité (Religion of Humanity) for positivists to fulfill the cohesive function once held by traditional worship. His ideas contributed to the rise of ethical culture societies and secular humanism. He died of stomach cancer in Paris at age 59. (D. 1857)

“Daily experience shows that the ordinary morality of religious men is not, at present, in spite of our intellectual anarchy, superior to that of the average of those who have quitted the churches. The chief practical tendency of religious conviction is … to inspire an instinctive and insurmountable hatred against all who have emancipated themselves, without any useful emulation having arisen from the conflict.”

— "The Positive Philosophy of Auguste Comte" (1853)

Clémence Royer

On this date in 1830, Clémence-Auguste Royer (née Augustine-Clémence Audouard) was born in Nantes, France. Her parents were Catholic royalists and didn’t marry until seven years after her birth. Her early education was in a convent school. Royer became a republican following the Revolution of 1848 and started to question other commonly held views. She obtained a teaching certificate and taught at girls schools in Wales, where she mastered English, and in France.

She read widely on science in these school libraries. In 1855, as a result of her inquiries, she rejected Catholicism thoroughly and devoted herself to science. She began to offer lectures on science and logic for women in Lausanne, Switzerland, in 1858.

Royer translated Charles Darwin’s Origin of Species into French in 1863. She controversially added a 60-page preface which used Darwin’s mechanism for evolution as part of an anti-religious argument, which Darwin did not make. By this time the book was in its third English edition and contained several strong references to a creator. Royer had been an evolutionist before reading Darwin, having been strongly influenced by the writings of Jean Baptiste LaMarck.

French scientists, especially atheists and anthropologists, were strongly influenced by evolution and natural selection as framed by Royer, who also discussed the implications of evolutionary theory for human beings and society in her introduction. It would be almost 10 years before Darwin himself grappled with these issues in The Descent of Man. Royer continued as Darwin’s official French translator until the third French edition of Origin was published in 1870.

Royer, despite not being a research scientist, remained a popular interpreter of science as well as a philosopher of science. As a woman, she was denied access to many learned societies, as well as university teaching positions. It has been argued by Jennifer Michael Hecht and others that Royer opened doors to women within the freethinking movement. In 1866 she had a son, René, by her lover and life partner, Pascal Duprat, a married man, which sharpened her concern about the major legal obstacles then present to unwed mothers and their children.

She published many books and articles and considered the pinnacle to be Natura rerum, her theory of nature. In 1900 she was named a Chevalier of the Legion of Honor for her contributions as “a woman of letters and a scientific writer.” Royer died in 1902 at age 71. Her son died of liver failure six months later in Indochina. (D. 1902)

“Yes, I believe in revelation, but a permanent revelation of man to himself and by himself, a rational revelation that is nothing but the result of the progress of science and of the contemporary conscience, a revelation that is always only partial and relative and that is effectuated by the acquisition of new truths and even more by the elimination of ancient errors.”

— Royer, preface to Darwin's "L'origine des espèces," cited in Jennifer Michael Hecht's "The End of the Soul" (2003)

Daniel Everett

On this date in 1951, linguist Daniel Everett was born in Holtville, Calif., to a working-class family. A voracious reader, Everett became interested in linguistics after viewing “My Fair Lady” as a high schooler. He met Keren Graham, the daughter of Christian missionaries, in high school and, at 17, became a born-again Christian. A year later, he and Keren married. After graduating from the Moody Bible Institute of Chicago in 1975, they both enrolled in an international evangelical organization, the Summer Institute of Linguistics (S.I.L.), with the mission of “spreading the Word of God” by translating the bible into the languages of preliterate societies.

Everett was chosen to work with the Piraha, a small tribe of about 350 people in the jungles of Brazil. S.I.L. had sent prior missionaries to this tribe before, but due to the complexity of the Piraha language, none had succeeded in mastering it. Among other challenges, it is a language that is as likely to be hummed or whistled, as it is to be spoken. Keren, Everett and their three young children were sent to the Piraha village at the mouth of Maici River. The Piraha have resisted all efforts from outside influences, steadfastly maintaining their own culture.

Everett’s conclusion that the Piraha language lacks grammatical recursion (sentences embedded within sentences, a concept promoted by foremost linguist Noam Chomsky and considered a cornerstone of language) has created controversy in the field of modern linguistics. Everett discovered the Piraha have no creation myths; they don’t draw pictures or make up stories about the ancient past. They believe in spirits, with which they may have a direct encounter, but “there’s no great god who created all the spirits,” Everett noted. (Science News, Dec. 2005).

Everett eventually lost his faith and became an atheist. It took 19 years before he told his wife and, when he did, their marriage ended and two of his three children disassociated themselves from him.

Everett served as chair of linguistics, languages and cultures at Illinois State University at Normal. His book, Don’t Sleep, There Are Snakes: A Life in the Amazon, was published by Random House in 2008: “The Pirahas have shown me that there is dignity and deep satisfaction in facing life and death without the comforts of heaven or the fear of hell, and of sailing towards the great abyss with a smile. And they have shown me that for years I held many of my beliefs without warrant. I have learned these things from the Pirahas, and I will be grateful to them for as long as I live.”

“I went from being a Christian missionary to an atheist.”

— Everett interview, New Scientist (Jan. 18, 2008)

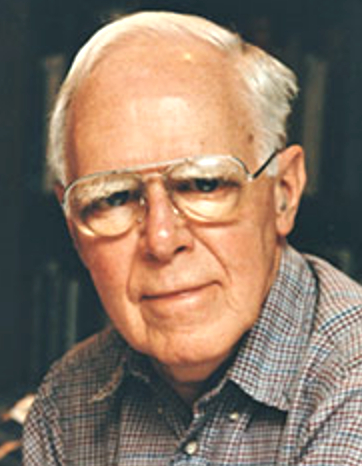

Martin Gardner

On this date in 1914, Martin Gardner was born in Tulsa, Okla. He graduated Phi Beta Kappa from the University of Chicago in 1936. After Navy service during WWII, he worked as a reporter for the Tulsa Tribune. His “Mathematical Games” column for Scientific American, originally called “Soma Cube,” ran from 1956-86 and popularized recreational mathematics in the U.S.

Among the more than 100 books and booklets Gardner published are Fads and Fallacies in the Name of Science, On the Wild Side, his collected Skeptical Inquirer columns, The New Age, Notes of a Fringe Watcher (1991) and The Healing Revelation of Mary Baker Eddy (1993), which exposed her plagiarism. Gardner called his 1999 work The Whys of a Philosophical Scrivener the book he liked best, calling it “a detailed account of everything I believe.”

He called himself a “philosophical theist,” rejecting all supernaturalism and established religion but embracing the idea of a personal god and an afterlife. (Spectrum magazine, Oct. 17, 2008.) He also called himself a “fideist,” which describes the position that faith supersedes reason, i.e., when someone chooses to believe in a god or gods because it’s comforting, not because there’s evidence. It’s a proposition that is many centuries old among philosophers.

In a December 1995 Scientific American article, Gardner said, “I grew up believing that the Bible was a revelation straight from God. … It lasted about halfway through my years at the University of Chicago.” He retired in 1979 and moved with his wife Charlotte to Hendersonville, N.C., but continued to write math articles and revise some of his older books. After Charlotte died in 2000 he moved to Norman, Okla., where his son James was an education professor. He died there at age 95. (D. 2010)

“[B]ad science contributes to the steady dumbing down of our nation. Crude beliefs get transmitted to political leaders and the result is considerable damage to society. We see this happening now in the rapid rise of the religious right and how it has taken over large segments of the Republican Party. I think fundamentalist and Pentecostalist Pat Robertson is a far greater menace to America than, say, Jesse Helms who will soon be gone and forgotten.”

— Gardner interview, Skeptical Inquirer (March/April 1998)

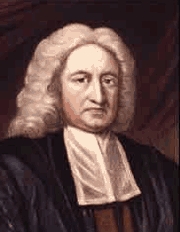

Edmund Halley

On this date in 1656, astronomer Edmund Halley was born in England. His father was a wealthy London soapmaker. The Royal Society published a scientific paper by Halley when he was only 19. He cut short his college career to travel to St. Helena, the southernmost point of the British Empire, where he catalogued 341 stars, discovered a star cluster and made the first complete observation of a transit of Mercury.

King Charles II conferred a degree from Oxford upon Halley without requiring an exam. At 22 he became one of the youngest members admitted to the Royal Society. He had worked with Royal Astronomer John Flamsteed at Oxford and Greenwich. Flamsteed became Halley’s enemy and blocked his appointment to Oxford on account of Halley’s rationalist views in 1691. He married Mary Tooke in 1682 and they had three children.

Halley urged Newton to write his Principia Mathematica and published it for him. Halley remains famous for being the first to predict the return of the comet named for him, appearing every 75-76 years. After several posts, Halley finally secured a professorship at Oxford in 1703. When Flamsteed died, Halley became King George I’s astronomer in 1720. He was known during his day as “the infidel mathematician.” The Royal Society censured him for suggesting in 1694 that the story of Noah’s flood might be an account of a cometary impact.

While not all his theories proved correct, Halley made many important discoveries, innovations and inventions, such as the diving bell. He died at age 85. (D. 1741)

“That he was an infidel in religious matters seems as generally allowed as it appears unaccountable.”

— "Chalmers' Biographical Dictionary," cited by Joseph McCabe in "A Dictionary of Modern Rationalists" (1920)

Claude Lévi-Strauss

On this date in 1908, anthropologist and ethnologist Claude Lévi-Strauss was born to French Jewish parents living in Brussels. Lévi-Strauss was instrumental in the development of structuralism and structural anthropology, incorporating the structural linguistics of Ferdinand de Saussure into anthropological theory. He was dismissed from a teaching position in 1940 due to the Vichy racial laws in Nazi-occupied France. These same anti-Semitic laws would subsequently strip him of his French citizenship and force him to move to New York City to find work teaching at the New School for Social Research.

Lévi-Strauss’ time in New York, perhaps especially because he was working alongside other intellectuals in exile, proved massively influential on his work. Upon publication of Tristes Tropiques (1955) — part memoir, part travelogue, part philosophical treatise — he was recognized as one of the world’s foremost intellectuals.

He chaired the department of social anthropology at the Collège de France from 1959-82 and was elected to the Académie Française in 1973. He received nearly every major honor given to French intellectuals, including the Grand Cross of the National Order of the Legion of Honour. He is frequently referred to as the “father of modern anthropology.” His most influential and adventurous work, La Pensée Sauvage (The Savage Mind, 1962) documented an important debate with Jean-Paul Sartre over the nature of human agency, history and social change. In the book, Lévi-Strauss’ structuralism is presented as an alternative to Sartre’s existentialist philosophy.

He married Dina Dreyfus in 1932, Rose Marie Ullmo in 1946 and Monique Roman in 1954 and had sons, Laurent and Matthieu, with Ullmo and Roman. He died in Paris a few weeks short of his 101st birthday. (D. 2009)

PHOTO: Lévi-Strauss in 2005. UNESCO/Michel Ravassard photo.

“Personally, I’ve never been confronted with the question of God.”

— Lévi-Strauss, describing himself as an atheist, Time magazine (1966)

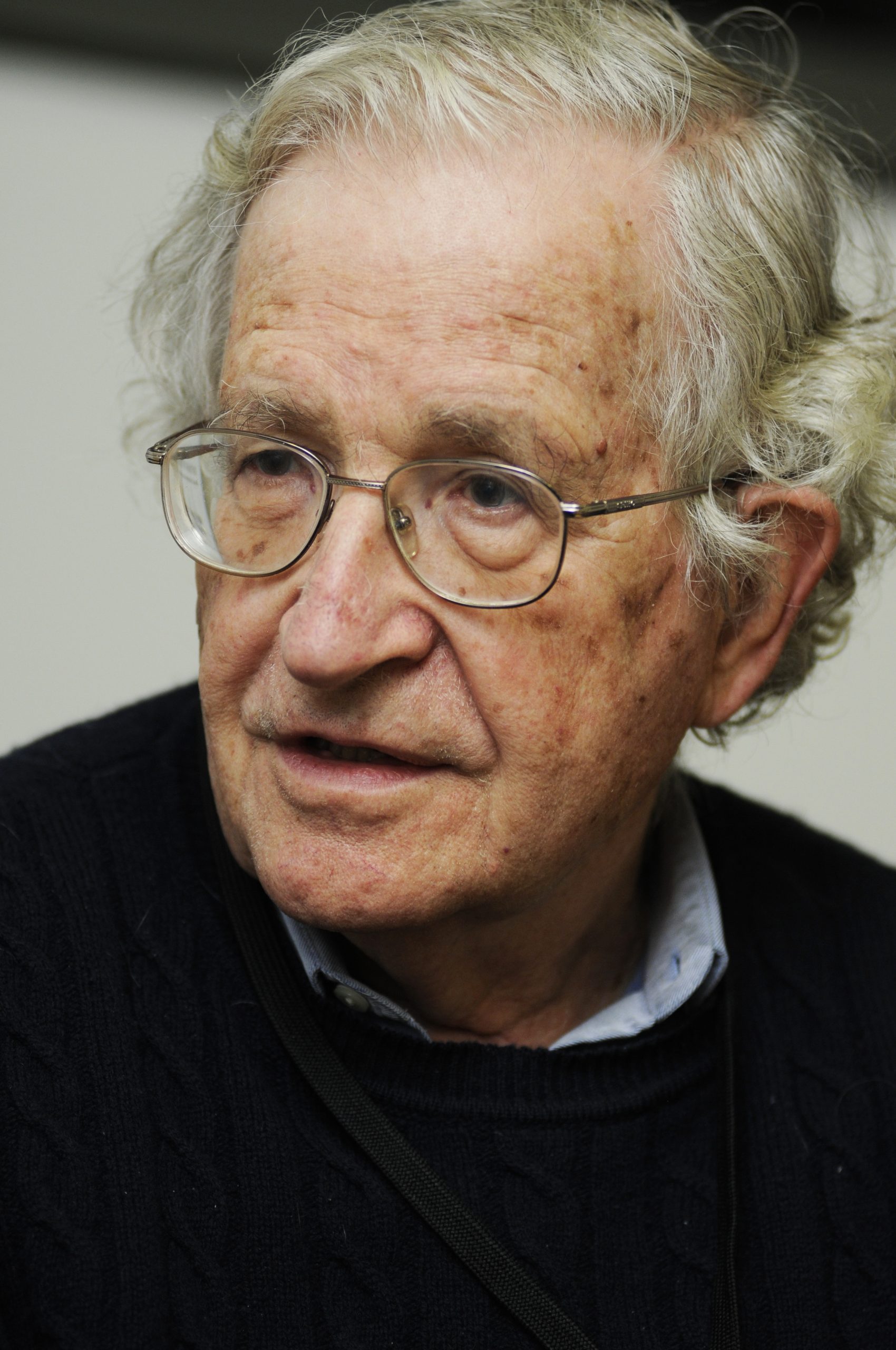

Noam Chomsky

On this date in 1928, Avram Noam Chomsky, the son of a Ukrainian immigrant Hebrew scholar, was born in Philadelphia. Although Chomsky would revolutionize the world of linguistics, politics has been close to his heart since childhood and has brought him even greater renown (and controversy). From an early age, Chomsky attended a day school that based its curriculum on the theories of John Dewey. As a teen he frequented New York City bookstores and places where Jewish intellectual men gathered. He received his B.A. (1949), M.A. (1951) and Ph.D. (1955) from the University of Pennsylvania.

He grew disenchanted as a Penn student with the structure of formal education and considered moving to a kibbutz in Palestine to promote Arab-Jewish cooperation. Then his interest in linguistics grew under the mentorship of Zellig Harris, founder of the first department of linguistics in the country, who convinced him to major in that field. Chomsky was Harris’ student from the undergraduate level, starting in 1946, through the doctoral level.

He married Carol Doris Schatz in 1949, a linguist he had known since childhood. In 1951 he was inducted into the Society of Fellows on a four-year term at Harvard University. Chomsky joined the faculty at MIT in 1955, working there in different research and academic positions for the next 60 years.

In 1957 he wrote Syntactic Structures, which revolutionized the field of linguistics and put Chomsky on the academic map. Prior to that book, most social scientists believed language and other human behaviors were learned through observation instead of being generated through more complex and innate processes.

In the 1960s Chomsky became one of the earliest and most outspoken critics of the Vietnam War. In 1967 he spent the night in jail for his involvement in the organization of a Vietnam War protest march at the Pentagon. His 1969 book, American Power and the New Mandarins, landed him on President Richard Nixon’s “enemies” list. In 1971, in Cambridge, England, Chomsky gave the Bertrand Russell Memorial Lectures, which were published as Problems of Freedom and Knowledge (1971). He has had numerous books, lectures, interviews and articles published, many of which are critical of U.S.-led atrocities in Vietnam, South and Central America, Laos and Cambodia.

His controversial book Counter-Revolutionary Violence: Bloodbaths in Fact and Propaganda (1973), co-authored with Edward S. Herman, was censored and ordered to be destroyed by its publisher, Warren Communications, because the book accused the U.S. of violence against native peoples. He continued to write monumental works on linguistics and politics, including Rules and Representations (1980), The Political Economy of Human Rights (1979), Terrorizing the Neighborhood: American Foreign Policy in the Post-Cold War Era (1991) and Manufacturing Consent: The Political Economy of the Mass Media (1988), co-authored with Herman.

More recently he published Occupy (2012), a short history of the Occupy movement, Failed States: The Abuse of Power and the Assault on Democracy (2006), Gaza in Crisis (2010) and Requiem for the American Dream (2017). After his wife died in 2008, he married Valeria Wasserman in 2014. He has three children.

“I am a child of the Enlightenment. I think irrational belief is a dangerous phenomenon, and I try to consciously avoid irrational belief.”

— Chomsky, interview with David Barsamian in "Chronicles of Dissent" (1992)