anthropologists

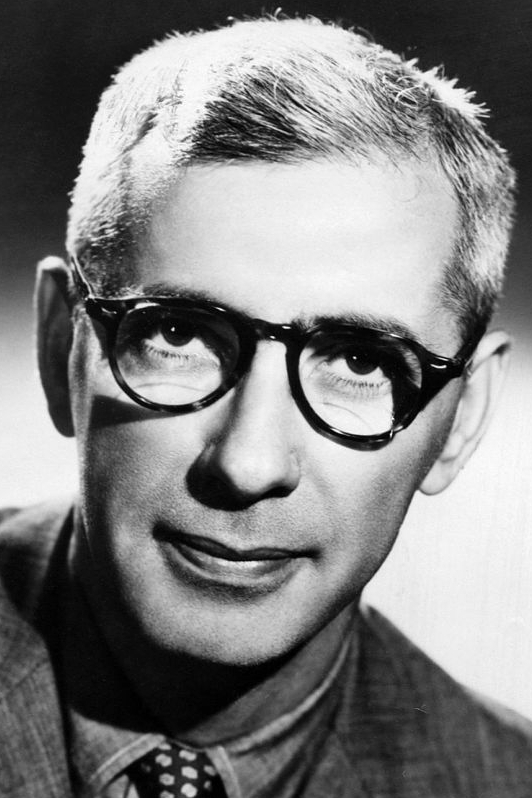

Ashley Montagu

On this date in 1905, Ashley Montagu (born Israel Ehrenberg) was born in East London. He adopted his new last name in homage of Lady Mary Montagu, a freethinking feminist from the 18th century. Montagu graduated from the University College- London and received a Ph.D. in anthropology from Columbia University in 1937. He broke ground as an anthropologist in writing about race. His book Man’s Most Dangerous Myth: The Fallacy of Race (1942) was his most influential work on that score.

Some of his 60 other books included Coming Into Being of the Australian Aborigines (1937), Race and Kindred Delusions (1939) and The Natural Superiority of Women (1953). Montagu applied his work as a social biologist in writing on diverse topics, including gun control, peace, evolution, marriage, children, emotions and even a biography, The Elephant Man, about the Victorian John Merrick, which was made into a movie in 1980. His numerous articles, popular and scientific, included “Nothing Can Be Said in Favor of Smoking” (1942). The American Humanist Association named the humanitarian “Humanist of the Year” in 1995.

A statement often attributed to him (primary source unknown): “The Good Book — one of the most remarkable euphemisms ever coined.” (D. 1999)

PHOTO: Montagu at age 53 in 1958.

“The scientist believes in proof without certainty, the bigot in certainty without proof. Let us never forget that tyranny most often springs from a fanatical faith in the absoluteness of one’s beliefs.”

— Montagu, "Science and Creationism" (1984)

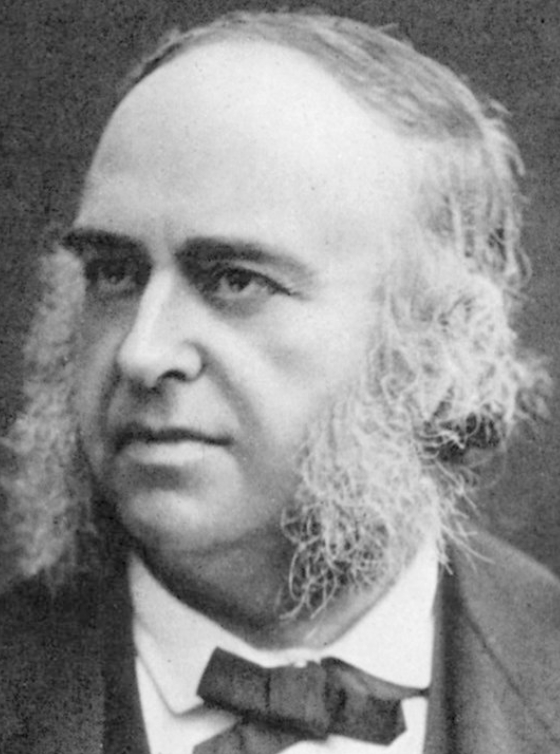

Paul Broca

On this date in 1824, Pierre Paul Broca was born in Sainte-Foy-la-Grande, France. He began attending medical school when he was only 17, graduated at 20 and later earned degrees in mathematics, literature and physics. Broca went on to become a professor of surgical pathology at the University of Paris and was an accomplished anatomist who advanced understanding of speech production in the brain. His most important achievement was discovering Broca’s area, a region of the brain responsible for speech production.

His work was also influential in cancer pathology and treatment of brain aneurysms. Broca founded the Anthropological Society of Paris in 1859, and his findings in anthropology often contradicted biblical teachings. Broca himself died, ironically, of a brain aneurysm. His brain was preserved after his death, becoming the inspiration for Carl Sagan’s 1974 book Broca’s Brain.

According to The End of the Soul by Jennifer Michael Hecht (2003), Broca thought that the more educated humans were, the less religious they would become. Broca also firmly supported natural selection: “Far from blushing in shame for my species because of its genealogy and parentage, I will be proud of all that evolution has accomplished.” (D. 1880)

“[Religion is] nothing more than a type of submission to authority.”

— Broca, "Bulletins de la Société d’anthropologie de Paris"

Eugenie Scott

On this date in 1945, anthropologist and educator Eugenie Carol Scott was born in La Crosse, Wis., to Virginia (neé Derr) and Allen Scott. She was raised in Christian Science by her mother and grandmother but later, influenced by her sister, joined a Congregational church.

She earned a B.S. and an M.S. from the University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee and a Ph.D. in biological anthropology from the University of Missouri in 1974. Her dissertation title was “Dental Evolution in Pre-Columbian Coastal Peru.”

Scott then joined the University of Kentucky in Lexington as a physical anthropologist. A citizens group proposed in 1980 that Lexington’s schools should teach creationism. She took a group of students to a debate in Missouri between her mentor James Gavan and “young Earth” creationist Duane Gish. Her group was “greatly dismayed,” she recalled later. “The scientist talked science, and the creationist connected to the audience and told good jokes and was really personable. And presented a lot of really bad science.” (New York Times, Sept. 2, 2013)

The scientific community saw the need to push back and in 1983 formed the National Center for Science Education (NCSE) with the goal of “defending the teaching of evolution in public schools.” Scott assumed the helm as its first national director in 1987. Based in Oakland, Calif., she served in that position for the next 27 years.

She had married Robert Black in 1965. After divorce, she married Thomas Sager in 1971. Their daughter, Carrie Ellen Sager, is an attorney specializing in state-church separation, employed as of this writing in 2022 as a staff attorney for HomeBase, The Center for Common Concerns, in El Cerrito, Calif.

“Scott describes herself as atheist but does not discount the importance of spirituality,” said a San Francisco Chronicle news story. (Feb. 7, 2003) “Science is a limited way of knowing, looking at just the natural world and natural causes. There are a lot of ways human beings understand the universe — through literature, theology, aesthetics, art or music.”

If she called herself an atheist to the Chronicle writer, it was out of character because Scott typically said she was a pragmatic humanist, at least in regards to her NCSE work. In another article, she joked that sometimes she thinks her first name is “Atheist” because she’s called “Atheist Eugenie Scott” so much. Evolutionary biologist Jerry Coyne has criticized her and NCSE for their “accommodationist” stance on religion, calling it “offensive and unnecessary — a form of misguided pragmatism.” (Discover magazine, May 27, 2009)

“You need to make it very clear you are not a humanist organization, you’re not an atheist organization, you’re not a religious organization, you are religiously neutral,” she remembers Fred Edwords of the American Humanist Association telling her. “You stand for science and science education.” (Interview with Canadian sociologist Tom Kaden, May 14, 2012)

The anti-evolutionists next invented a pseudoscience called “intelligent design” to invade schools. Scott served as a pro bono consultant in the landmark Kitzmiller v. Dover trial, in which federal Judge John Jones ruled in 2005 that it was a form of creationism and hence unconstitutional.

David Berlinski, author of “The Devil’s Delusion: Atheism and Its Scientific Pretensions,” wrote: “Eugenie Scott is a small squirrel-like creature who is often sent out to defend Darwin. Whenever doubts are raised, she withdraws a naturalistic nut from her cache and flaunts it proudly.” (Discovery Institute, March 17, 2006) Scott countered by calling herself “Darwin’s golden retriever,” playing on the description of biologist T.H.H. Huxley as “Darwin’s bulldog” for his spirited advocacy.

NCSE then waged battles in Florida, Texas and elsewhere against efforts allowing teachers to “teach the controversy” about evolution so students could “analyze and evaluate” the theories. (Scientific American, June 1, 2009) In Cobb County, Georgia, a school board ordered insertion of disclaimers in science textbooks that said “evolution is a theory, not a fact” and should be “critically considered.”

Scott was the recipient in 2012 of its Richard Dawkins Award by the Atheist Alliance of America, given to “individuals it judges to have raised the public consciousness of atheism.”

“My personal view is I’m not religious. I don’t accept the Christian view of things.”

— Interview with York University sociologist Tom Kaden for his research project on how people view the relationship between religion and science. (May 14, 2012)

Claude Lévi-Strauss

On this date in 1908, anthropologist and ethnologist Claude Lévi-Strauss was born to French Jewish parents living in Brussels. Lévi-Strauss was instrumental in the development of structuralism and structural anthropology, incorporating the structural linguistics of Ferdinand de Saussure into anthropological theory. He was dismissed from a teaching position in 1940 due to the Vichy racial laws in Nazi-occupied France. These same anti-Semitic laws would subsequently strip him of his French citizenship and force him to move to New York City to find work teaching at the New School for Social Research.

Lévi-Strauss’ time in New York, perhaps especially because he was working alongside other intellectuals in exile, proved massively influential on his work. Upon publication of Tristes Tropiques (1955) — part memoir, part travelogue, part philosophical treatise — he was recognized as one of the world’s foremost intellectuals.

He chaired the department of social anthropology at the Collège de France from 1959-82 and was elected to the Académie Française in 1973. He received nearly every major honor given to French intellectuals, including the Grand Cross of the National Order of the Legion of Honour. He is frequently referred to as the “father of modern anthropology.” His most influential and adventurous work, La Pensée Sauvage (The Savage Mind, 1962) documented an important debate with Jean-Paul Sartre over the nature of human agency, history and social change. In the book, Lévi-Strauss’ structuralism is presented as an alternative to Sartre’s existentialist philosophy.

He married Dina Dreyfus in 1932, Rose Marie Ullmo in 1946 and Monique Roman in 1954 and had sons, Laurent and Matthieu, with Ullmo and Roman. He died in Paris a few weeks short of his 101st birthday. (D. 2009)

PHOTO: Lévi-Strauss in 2005. UNESCO/Michel Ravassard photo.

“Personally, I’ve never been confronted with the question of God.”

— Lévi-Strauss, describing himself as an atheist, Time magazine (1966)

Richard Leakey

On this date in 1944, Richard Erskine Frere Leakey was born in Nairobi, Kenya, to the famous archaeologists Louis and Mary Leakey. As a child, Leakey accompanied his family on archaeological expeditions and discovered his first fossil when he was 5. After dropping out of high school when he was 16, Leakey entertained various careers such as leading safaris, but ultimately chose to follow in his parents’ footsteps, becoming an accomplished paleoanthropologist.

His achievements included finding the full skeleton of a 1.6 million-year-old Homo erectus known as “Turkana Boy” and co-discovering in 1972 the “Black Skull” (also known as “1470”), the earliest australopithecine fossil discovered to date. He also wrote numerous books, including Origins, co-written with Roger Lewin (1977), The Making of Mankind (1981), Origins Reconsidered (with Lewin, 1992), The Sixth Extinction (with Lewin, 1995) and Wildlife Wars: My Fight to Save Africa’s Natural Treasures (with Virginia Morell, 2001).

Caned in school as a child for missing chapel, he vowed to never become Christian. “I didn’t ever have religion,” Leakey said during an interview with the Academy of Achievement on June 21, 2017. Since his uncle was the Anglican archbishop of East Africa, Leakey’s professed atheism didn’t sit well with some of his family, friends and teachers.

In the early 1960s he started a trapping and skeleton supply business with Kamoya Kimeu, soon expanding it into photographic safaris. He made his first forays into paleoanthropology and met archaeologist Margaret Cropper. In 1965 they married but divorced in 1969 after having a daughter, Anna. He married zoologist Meave Epps in 1970 and they had two daughters: Louise, also a paleoanthropologist, and Samira.

He worked with his father at the Centre for Prehistory and Palaeontology but differences led Leakey in a different direction. With others he started working to “Kenyanise” the National Museum. Over the next decade he took part in expeditions that made a number of stunning archaeological discoveries. In 1990 he was appointed the first chairman of the Kenya Wildlife Service and spearheaded efforts to stop elephant poaching. A plane he was piloting crashed in 1993 and both his legs had to be amputated. He told President Daniel Arap Moi, a religious man, not to pray for him. (Interview in The Humanist, June 29, 2012)

Leakey left Kenya in 2002 to teach anthropology at Stony Brook University in New York and chair the Turkana Basin Institute. He was appointed in 2007 as interim chairman of Transparency International’s Kenya branch and was elected a Fellow of the Royal Society. In 2013 he received the Isaac Asimov Science Award from the American Humanist Association. President Uhuru Kenyatta appointed Leakey chairman of the board of the Kenya Wildlife Service in 2015.

In a 2010 interview with Richard Dawkins for the 2008 documentary “The Genius of Charles Darwin,” Leakey said, “Surely, [evolution] should be the pride and joy of African leaders. But the faith brigade, whether they’re evangelical Christians, whether they’re conservative Catholics, whether they’re Islamic fundamentalists, are quite worried about this concept and are trying desperately to persuade ongoing future generations to have nothing to do with it.”

He died in Kenya of undisclosed causes 14 days after his 77th birthday. (D. 2022)

PHOTO: Leakey in 1986. Rob Bogaerts/Anefo photo. CC 4.0

“I myself do not believe in a god who has or had a human form and to whom I owe my existence. I believe it is man who created God in his image and not the other way round.”

— Leakey, "One Life: An Autobiography" (1983)