September 26

George Gershwin

On this date in 1898, composer George Gershwin (né Jacob Bruskin Gershowitz) was born in Brooklyn, N.Y. Of the three boys in the family, only his older brother Ira, later George’s lyricist, had a bar mitzvah. According to biographer Rodney Greenberg, “This religious milestone apparently meant little to Ira himself. The fact that Rose and Morris never imposed it upon George and Arthur means that, by the time they became teenagers, the family had left their East European Jewish origins behind and were living a secular existence in New York’s cosmopolitan melting pot.”

Gershwin’s named sources of “inspiration” were not gods or prophets but two other nonbelieving songwriters: Irving Berlin and Jerome Kern, according to biographer Edward Jablonski in Gershwin: A Biography. Self-taught on the piano, Gershwin started writing songs as a teen, quickly advancing from Tin Pan Alley to Broadway musicals. Considered by many to be America’s greatest composer, he wrote memorable standard after standard, including “Lady, be Good!” “Strike Up the Band,” “Funny Face,” “The Man I Love,” “Embraceable You,” “Somebody Loves Me” and “They Can’t Take That Away from Me.” His more serious work included “Rhapsody in Blue” (1924), “Piano Concerto in F” (1925), “Porgy and Bess “(1934), and “Three Preludes” (1926).

At the height of his career at age 38 in 1937, he died during surgery to remove a brain tumor. He had never married and at the time of his death lived in a house owned by lyricist Yip Harburg. (D. 1937)

It Ain’t Necessarily So

It ain’t necessarily so, (repeat)

De t’ings dat yo’ li’ble

To read in de Bible,

It ain’t necessarily so.Li’l David was small, but oh my! (repeat)

He fought big Goliath

Who lay down an’ dieth!

Li’l David was small, but oh my!Oh, Jonah, he lived in de whale, (repeat)

Fo’ he made his home in

Dat fish’s abdomen.

Oh, Jonah, he lived in de whale.Li’l Moses was found in a stream, (repeat)

He floated on water

Till Ole Pharaoh’s daughter

She fished him, she says, from that stream.It ain’t necessarily so, (repeat)

Dey tell all you chillun

De debble’s a villun,

But ’tain’t necessarily so.To get into Hebben don’ snap for a sebben!

Live clean! Don’ have no fault.

Oh, I takes dat gospel

Whenever it’s poss’ble,

But wid a grain of salt.Methus’lah lived nine hundred years, (repeat)

But who calls dat livin’

When no gal’ll give in

To no man what’s nine hundred years?I’m preachin’ dis sermon to show,

It ain’t nessa, ain’t nessa,

ain’t nessa, ain’t nessa,

Ain’t necessarily so.— Music by George Gershwin, lyrics by Ira Gershwin (1935)

Charles Bradlaugh

On this date in 1833, England’s best-known proponent of atheism, reformer Charles Bradlaugh, was born in London. He left school at age 11 to earn his living. When he announced his freethought views, he was forced to leave his family home and found support among other freethinkers, including the children of oft-jailed publisher Richard Carlile. Bradlaugh worked as a coal merchant. After joining the army, he worked as a solicitor’s clerk, learned the law and became an attorney.

He wrote and lectured about freethought under the pseudonym “Iconoclast.” Bradlaugh briefly became editor of the freethinking bi-weekly periodical The Investigator in 1858. By the time he became co-editor of the National Reformer in 1860, he was a famed social reformer and orator, known in England and abroad. In 1866 he founded the National Secular Society. Bradlaugh had two daughters and one son with his wife, whose serious drinking problem broke up the family in 1870.

Bradlaugh’s challenge in 1868-69 of the Security Laws, inhibiting distribution of controversial periodicals, brought their repeal. He also championed land reform. In 1876, he and colleague Annie Besant were prosecuted for “obscenity” for republishing a birth control booklet, The Fruits of Philosophy, by American doctor Charles Knowlton. After a long trial, the pair were convicted and faced jail and fines but were freed on a technicality. Bradlaugh was urged to run for Parliament in 1868, placing fifth. He ran several times before winning in 1880 but was refused seating because he would not take the religious oath.

Bradlaugh was reelected four times before finally prevailing in his fight to be seated in 1886, but the legal fight had drained him financially. Bradlaugh persuaded Parliament to pass a bill permitting the right to affirm in 1888. Bradlaugh lectured three times in the U.S. in the 1870s and was warmly received in India during his 1889 visit. His only surviving child, Hypatia Bradlaugh Bonner, took up the freethought/reform cudgels, also defending her father’s reputation from numerous “death-bed conversion” fables. D. 1891.

“I maintain that thoughtful Atheism affords greater possibility for human happiness than any system yet based on, or possible to be founded on, Theism, and that the lives of true Atheists must be more virtuous — because more human — than those of the believers in Deity, the humanity of the devout believer often finding itself neutralized by a faith with which that humanity is necessarily in constant collision.”

— Bradlaugh, "A Plea for Atheism" (1929)

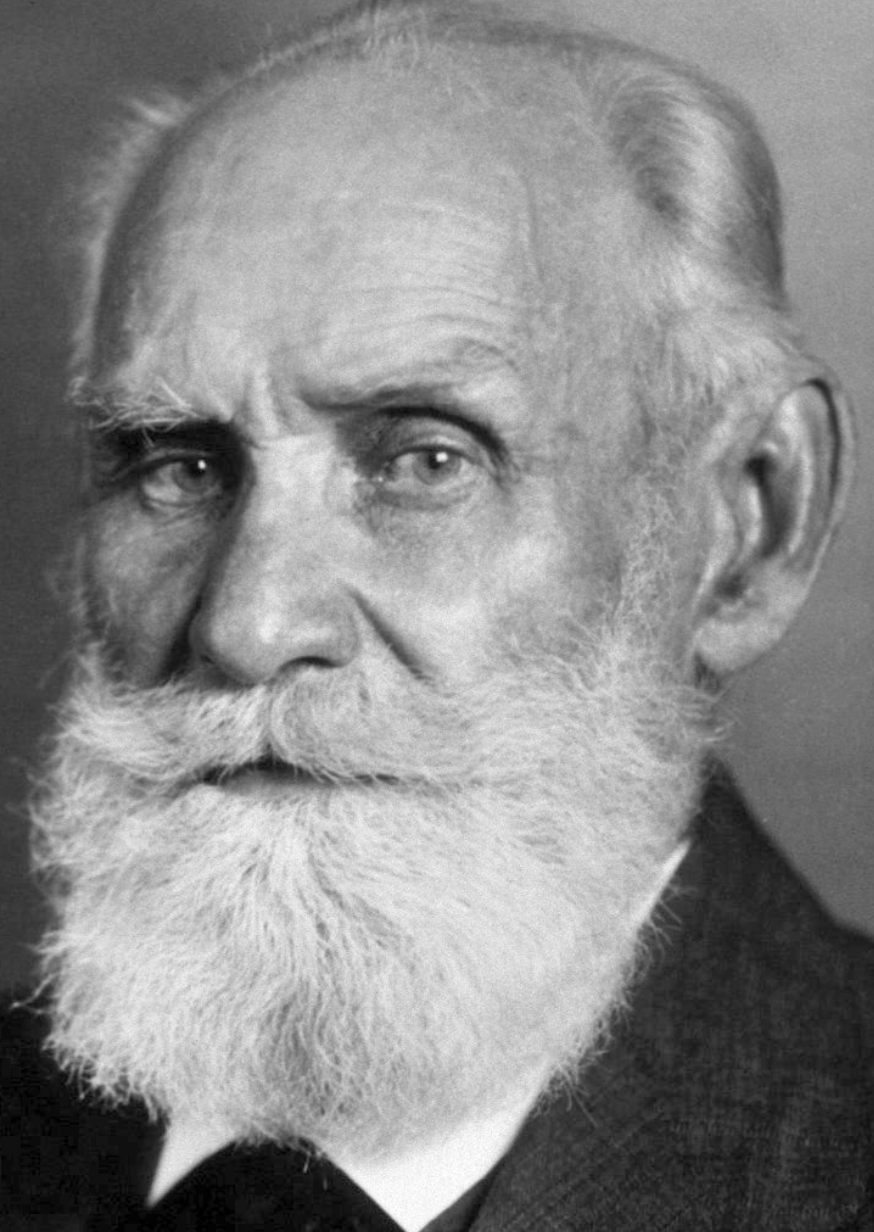

Ivan Pavlov

On this date in 1849, Ivan Petrovich Pavlov was born in Ryazan, Russia. He enrolled in Ryazan Ecclesiastical Seminary in the 1860s. In 1870 he dropped out in order to study natural sciences at the University of St. Petersburg. He graduated in 1875 and went on to attend the Academy of Medical Surgery. Pavlov became a professor of pharmacology at the Military Medical Academy in 1890 and director of the department of physiology at the Institute of Experimental Medicine in 1891, where he studied the physiology of the digestive system, often using dogs as research subjects.

He wrote books about his research, including Work of the Digestive Glands (1897). In 1904 he earned the Nobel Prize in Physiology and Medicine for his work with digestive organs. Pavlov married his wife, Serafima, in 1881.

Despite Pavlov’s influential research on the digestive system, he is most famous for his discovery of classical conditioning: teaching an animal to associate a reflex with an unrelated stimulus. Pavlov made the discovery while researching the salivary glands of dogs, after he noticed that dogs salivated when they anticipated food in addition to when they began eating. This led him to condition the dogs to begin salivating when they saw or heard a variety of stimuli, most famously, bells. He accomplished this by ringing a bell every time he fed the dogs, making them associate bells with food.

Pavlov described himself as an atheist who lost his faith when he was a seminary student. “In regard to my religiosity, my belief in God, my church attendance, there is no truth in it; it is sheer fantasy,” Pavlov told his student Evgenii Mikhailovich Kreps in the 1920s, according to the article “Pavlov’s Religious Orientation” by George Windholz (1986). Windholz also quoted Pavlov as saying, “There are weak people over whom religion has power. The strong ones — yes, the strong ones — can become thorough rationalists, relying only upon knowledge, but the weak ones are unable to do this.” D. 1936.

“Humans saved themselves by creating religion, which enabled them to maintain themselves somehow, to survive in the midst of an uncompromising, all-powerful nature. It is a very basic instinct that is thoroughly rooted in human nature.”

— Pavlov, quoted in “Pavlov’s Religious Orientation,” Vol. 25 of the Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion, 1986

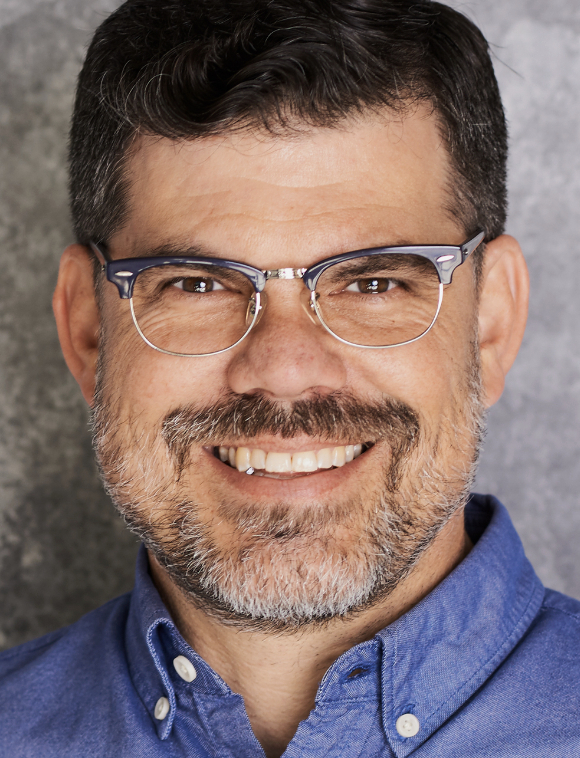

Ryan Bell

On this date in 1971, writer, educator and former Seventh-day Adventist pastor Ryan J. Bell was born in Parma, Ohio, to parents who were United Methodists. He moved with them when he was 6 to California in an effort to revive their faltering marriage by moving in with his maternal Adventist grandparents near Loma Linda.

In his teens, he told the Los Angeles Times in 2014, he didn’t drink, smoke or swear. Eating meat was forbidden. “I didn’t believe in evolution because my grandparents didn’t believe,” he said. After earning an undergraduate degree at the Adventist Weimar Insitute in nothern California, he received a master of divinity degree from Andrews University in Berrien Springs, Mich., and a doctor of ministry degree from Fuller Theological Seminary in Pasadena, Calif.

He had moved in 2005 with his wife and two young daughters to Hollywood, taking over the ministry at an Adventist church, where, according to the Times article, he “focused less on individual salvation than social justice. It wasn’t long before he was speaking out against Bank of America for what he considered predatory lending practices. Or demonstrating during the Occupy takeover of the lawns at City Hall. Or advocating for gay rights and marriage equality.”

Then, the story said, “After 17 years of marriage, he and his wife were headed for a divorce. … [A]fter a long battle with regional Adventist officials on almost every major point of theology, he agreed to resign.” He announced he was embarking on a journey to “try on” atheism for a year: “For the next 12 months I will live as if there is no God. I will not pray, read the Bible for inspiration, refer to God as the cause of things or hope that God might intervene and change my own or someone else’s circumstances.”

That led to him losing his positions at Azusa Pacific University and Fuller Theological Seminary. “Friendly Atheist” blogger Hemant Mehta started a fundraising campaign, which raised over $27,000 to help Bell through his unemployment.

At the end of “A Year Without God,” Bell told National Public Radio in 2014 that he felt like atheism was “an awkward fit” and that he also felt uncomfortable around his former Christian friends. “I think before, I wanted a closer relationship to God, and today I just want a closer relationship with reality.”

In 2015 he launched a project called Life After God and the Life After God podcast. He tweets at @ourlifeaftergod. He joined the Clergy Project and became national organizing manager for the Secular Student Alliance and humanist chaplain at the University of Southern California.

In a letter to the editor of Pasadena Now (April 14, 2020) that asked for a moment of silence instead of prayer at city council meetings, he wrote: “Our urgent need is not to invoke a higher power but to recognize that when we acknowledge our shared humanity, we become that power. … But let us not outsource our responsibility to a ‘higher power’ when the thing we need is right here, within our reach.”

“I don’t think that God exists. I think that makes the most sense of the evidence that I have and my experience.”

— Interview, NPR's "All Things Considered" (Dec. 27, 2014)