October 14

Katha Pollitt

On this date in 1949, writer and atheist Katha Pollitt was born in Brooklyn, N.Y. Her father was a Protestant lawyer and her Jewish mother worked in real estate. Pollitt earned a bachelor of arts degree from Radcliffe and a master of fine arts from Columbia University. The Washington Post called her “Subject to Debate” column, which The Nation started publishing in 1994, “the best place to go for original thinking on the left.” Pollitt has received a National Endowment for the Arts grant and a Guggenheim Fellowship for her poetry. Her 1982 book, Antarctic Traveller, won the National Book Critics Circle Award.

Her poems have appeared in The New Yorker, The Atlantic, The New Republic, The Yale Review, Poetry and Antaeus. A collection of her writings, Reasonable Creatures: Essays on Women and Feminism, was published by Knopf in 1994. The title was an ode to Mary Wollstonecraft, who wrote, “I wish to see women neither heroines nor brutes, but reasonable creatures.” Her second book of essays, Subject to Debate: Sense and Dissents on Women, Politics, and Culture, was published in 2001.

After she was named FFRF’s Freethought Heroine of the Year in 1995, she wrote about FFRF’s annual convention in a column called “No God, No Master.” Katha forthrightly volunteers her atheism and defends rationalism and the separation of church and state in her columns, during interviews and on national TV programs. Her outspoken, official dissent from the “official American civic religion” brought her an FFRF “Emperor Has No Clothes Award” in 2001. She was 2013’s Humanist Heroine for the American Humanist Association and received Planned Parenthood’s Maggie Award in 1993.

In 1987 she married Randy Cohen, author of The New York Times Magazine column “The Ethicist.” Before divorcing, they had a daughter, Sophie Pollitt-Cohen, born in 1987. In 2006 she married political theorist Steven Lukes.

Her book Pro: Reclaiming Abortion Rights was published in 2014 and was written to respond to the “feeling among many pro-choice people that we need to be more assertive, less defensive.” In the book she argues that the decision should not be looked at as the action of a woman thinking independently because abortion requires the “cooperation of many people beyond the woman herself.”

In 2017 she was the recipient of FFRF’s new Forward Award, which recognizes individuals who have moved society forward. Her acceptance speech, “Right-wing Christianity in the Age of Trump,” is here.

“I’m going to close with the thought that nothing good will happen if people don’t fight for it. And that’s where you all come in — the Freedom From Religion Foundation, the ACLU, a whole bunch of other wonderful civil liberties and civil rights organizations.”— Pollitt, FFRF Forward Award acceptance speech (Sept. 15, 2017)

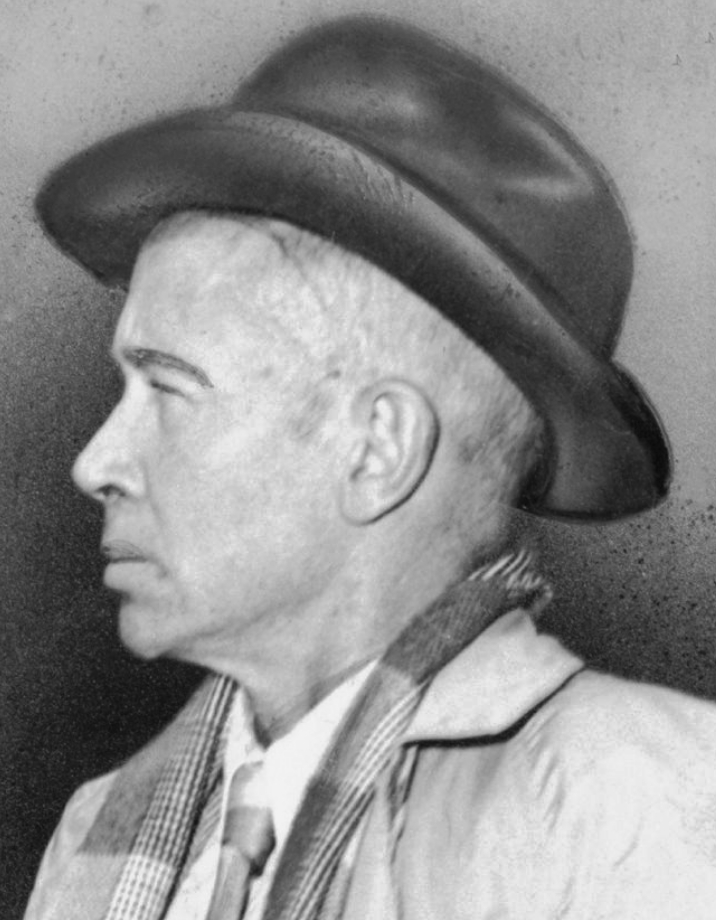

E. E. Cummings

On this date in 1894, Edward Estlin “E.E.” Cummings was born in Cambridge, Massachusetts. His father was a Unitarian minister and Harvard professor. Cummings graduated magna cum laude in Greek and English from Harvard in 1915 and earned his master’s there the following year. He volunteered to serve in France in 1917 as part of an ambulance group. He and a pacifist friend were falsely imprisoned for treason for four months in a French detention camp, which inspired his successful, anti-authoritarian novel The Enormous Room (1922).

His first book of poetry, Tulips and Chimneys (1923), was also a success. For many years Cummings’ work schedule involved painting in the afternoons and writing in the evenings. Although he wrote love poetry in some depth, he is known for his iconoclastic, satiric and playful attacks on the establishment, as well as for his use of the lower case, including the first two initials of his name.

Cummings was married three times; the third and last marriage was happy. Cummings was awarded the Guggenheim Fellowship in 1951. The collected edition of his works, Poems, 1923-54, was published in 1954. He was awarded the Bolingen Prize in 1958 and a two-year grant of $15,000 from the Ford Foundation in 1959.

He died of a stroke at age 67 at Memorial Hospital in North Conway, N.H. (D. 1962)

PHOTO: Cummings in 1953; photo by Walter Albertin.

the Cambridge ladies who live in furnished souls

are unbeautiful and have comfortable minds

(also, with the church’s protestant blessings

daughters, unscented shapeless spirited)

they believe in Christ and Longfellow, both dead— Cummings, excerpt, "the Cambridge ladies who live in furnished souls," "Tulips and Chimneys" (1923)

Hannah Arendt

On this date in 1906, German-born American political philosopher Johanna “Hannah” Arendt was born in Linden, Prussian Hanover, in the German Empire. In 1924 Arendt enrolled at the University of Marburg to study under Martin Heidegger, the foremost existential phenomenologist of the 20th century. Arendt, born into a secular family of German Jews, was briefly imprisoned by the Gestapo in 1933, after which she fled to Czechoslovakia, then to Geneva, then Paris, and finally to New York in 1941.

In 1951 she published The Origins of Totalitarianism, a study of the Nazi and Stalinist regimes. Next, in 1958, Arendt published The Human Condition — “an original philosophical study that investigates the fundamental categories of the vita activa (labor, work, action).” (Stanford Encyclopedia). After writing The Human Condition, which was to be her most important philosophical work, Arendt traveled to Israel to attend the trial of Adolf Eichmann, a Nazi war criminal. Her recounting of the trial, Eichmann in Jerusalem: A Report on the Banality of Evil (1963), is her most controversial and well-known work.

Arendt was a devoted secularist and humanist. In her book On Revolution (1963), she explored the religiosity of modern democracies. She contended that emerging democracies in the West mimicked the divine source of legal authority that their absolutist predecessors had claimed. According to Arendt, founders of European and American democracies feared that, without a sacred sanction for their new democratic governments, their often violent struggles for freedom would be seen as illegitimate.

Arendt’s secularism was frequently the source of controversy in postwar debates. She opposed Zionist nationalism and sought to engage with Judaism on political, rather than religious, terms. A heavy smoker, she died in her apartment at age 69 of a heart attack and was cremated. (D. 1975)

PHOTO: Arendt at age 18.

“The defiance of established authority, religious and secular, social and political, as a worldwide phenomenon may well one day be accounted the outstanding event of the last decade.”

— Arendt, “Civil Disobedience,” "Crises of the Republic" (1969)