May 20

Stephen Girard

On this date in 1750, Stephen Girard was born in Bordeaux, France. The freethinking philanthropist, who settled in Philadelphia in 1776, liked to say he started life with a sixpence. When he died he was the wealthiest man in America.

Girard went to sea as a cabin boy before he was 14 and worked his way up to commander. He opened a store in his adopted city, then became a ship owner and banker. During the yellow fever outbreak in 1793, when half the residents fled, Girard became a hero. He not only opened his pocketbook to help but volunteered as nurse and hospital manager for two months, working directly with the sick and dying.

Girard, an arch-critic of clergy and Christianity, though he donated to individual churches, named his sailing ships after freethinkers such as Voltaire. Biographer Stephen Simpson wrote that “his opinions were atheistical” and that Girard “utterly disbelieved in all modes of a future existence, and who rejected with inward contempt every formulary of religion, as idle, vain, and unmeaning.”

He left nearly his entire estate, valued at $7.5 million, to charity. He willed more than $5 million for the construction and endowment of a college for orphans, instructing that there should be no sectarian control or instruction (see quote below). Writing in 1894 in Four Hundred Years of Freethought, Samuel Putnam noted the school had about 1,500 students but that Girard’s provisions had been “shamefully violated.” (D. 1831)

"I enjoin and require that no ecclesiastic, missionary, or minister of any sect whatever shall ever hold or exercise any station or duty whatever in the said college; nor shall any such person ever be admitted for any purpose, or as a visitor, within the premises appropriated to the purpose of the said college."

— Girard's bequest terms in endowing a college for orphans, "Biography of Stephen Girard, with his Will Affixed" by Stephen Simpson (1832)

Honoré de Balzac

On this date in 1799, Honoré de Balzac was born in France. Educated by the Oratorian priests at Vendome College, Balzac became a lawyer’s clerk at his parents’ insistence. When he turned to writing, his parents reduced his allowance. Balzac worked in legendary privation for the next decade, honing his skill with his first unsuccessful novels. Success came in 1830, when he produced the first part of his 47-volume La Comédie humaine.

The prolific writer also wrote 24 unrelated novels. Skepticism pervades Balzac’s many masterpieces, including Pere Goriot and Cousin Bette. He did not marry until later in life but died at age 51, five months after marrying his longtime love Ewelina Hańska. (D. 1850)

“I am not orthodox, and I do not believe in the Roman Church. I think that if there is a scheme worthy of our kind it is that of human transformations causing the human being to advance toward unknown zones. That is the law of creations inferior to ourselves; it ought to be the law of superior creations. Swedenborgianism, which is only a repetition in the Christian sense of ancient ideas, is my religion, with the addition which I wish to make to it of the incomprehensibility of God.”

— Letter to Ewelina Hańska, his future wife (May 31, 1837)

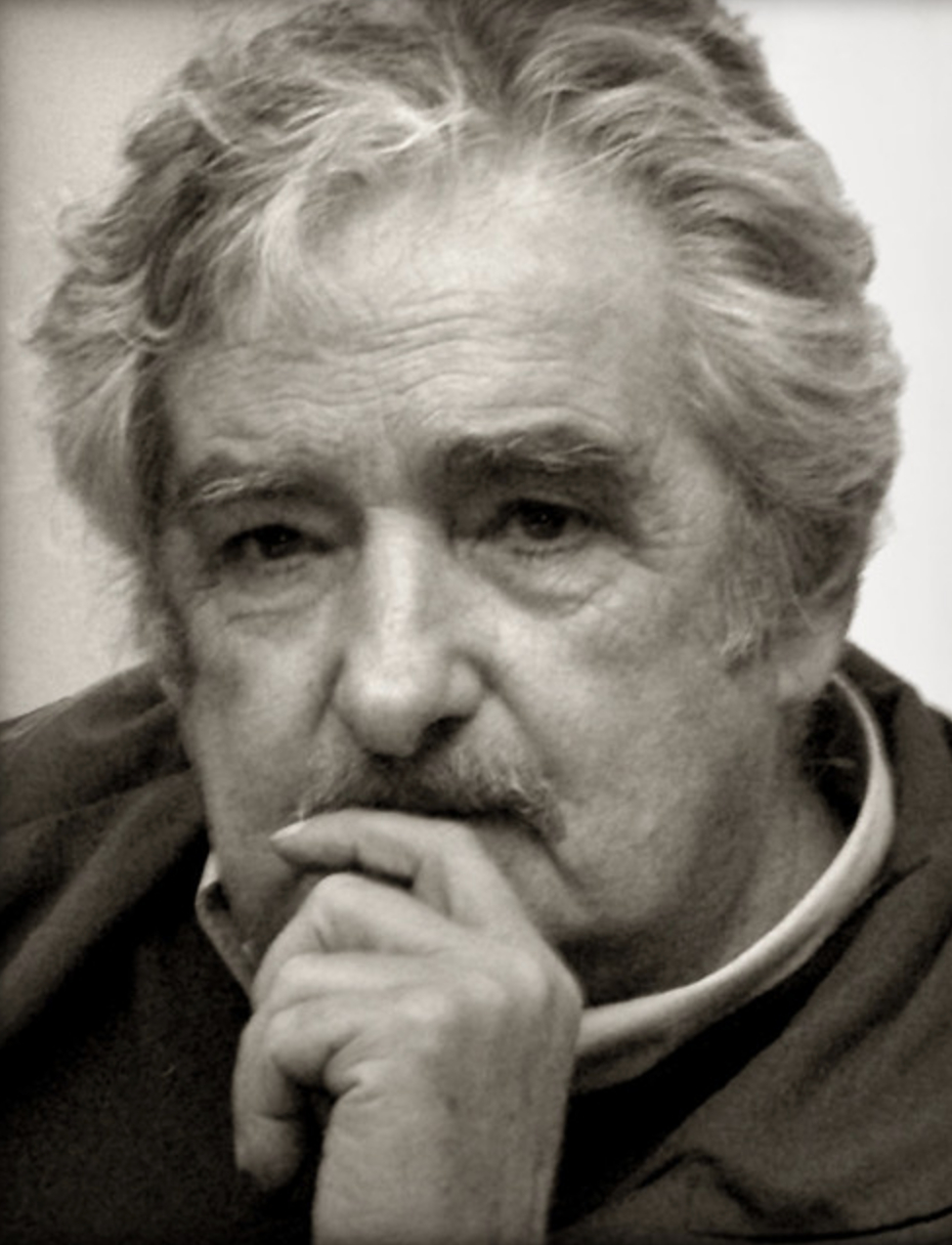

José Mujica

On this date in 1935, José Alberto Mujica Cordano, 40th president of Uruguay, was born in Montevideo. When Mujica was 7, his farmer father went bankrupt and died shortly after. Mujica worked delivering baked goods and as a teen was an avid bicyclist. Politically involved as a youth, he joined the Tupamaros, revolutionaries fighting Uruguay’s brutal dictatorship in the 1960s. He was imprisoned for 14 years, many spent in solitary confinement. He was freed in 1985, as the dictatorship waned, under a general amnesty.

First elected to the Senate in 2000, Mujica served as agriculture minister from 2005-08 before winning the presidential election in 2009 as a member of a coalition of left-wing parties. He led a party known as the Movement of Popular Participation (MPP) that he formed with fellow Tupamaros. During his presidency from 2010-15, the economy prospered and gay marriage, abortion and marijuana were legalized. He was nominated for the Nobel Peace Prize in 2012.

He was often referred to as “the world’s poorest” and “the world’s most humble” president since he donated 90% of his salary to charity, making his income similar to the average wage. Never taking residence in the presidential house, Mujica lived in a one-bedroom house on a small farm on the outskirts of Montevideo with his wife Lucía Topolansky and their three-legged dog Manuela.

He died a week short of his 90th birthday at his farm on the outskirts of Montevideo. The government declared three days of national mourning and an estimated 100,000 people attended his funeral. (D. 2025)

PHOTO by Vince Alongi

"I still have not been able to believe in God."

— El Espectador, Colombian daily newspaper (May 16, 2012)

John Stuart Mill

On this date in 1806, John Stuart Mill was born in England. Mill, who met Jeremy Bentham as a young man, became a champion of individual liberty. With Bentham, Mill advanced utilitarianism, a philosophy advocating that the role of government is to create the greatest amount of good with the least evil. Mill, known for his clear writing style and compelling logic, advanced and popularized such ideals as social and sexual equality, the public ownership of national resources, and political liberty.

Mill was tutored at a tender age by his father, James Mill, who was an agnostic. Mill could not remember a time when he could not read Greek, writing in his autobiography that he started Greek study by age 3.

Mill wrote in his Autobiography (1873) that his father “impressed upon me from the first, that the manner in which the world came into existence was a subject on which nothing was known: that the question, ‘Who made me?’ cannot be answered, because we have no experience or authentic information from which to answer it; and that any answer only throws the difficulty a step further back, since the question immediately presents itself, ‘Who made God?’ “

Even as a teen, Mill wrote a defense of skeptic Richard Carlile, jailed for six years for “blasphemous libel.” After a clerkship in India House (headquarters of the East India Company), Mill became part of the “philosophic Radicals,” and wrote for a number of journals. A System of Logic, in two volumes, came out in 1843, followed by Principles of Political Economy (1848), On Liberty (1859), Utilitarianism (1863) and The Subjection of Women (1869). The latter book was influenced by his wife Harriet Hardy Taylor, a longtime friend whom Mill married in 1851.

In On Liberty, a work dedicated to his wife, who died in 1858, Mill rejected a standard of ethics predicated on obedience, or the crushing of individuality, whether by “enforcing the will of God or the injunctions of men.” Mill termed Christianity “essentially a doctrine of passive obedience; it inculcates submission to all authorities found established.” Mill was a member of Parliament from 1865-68, rising to the defense of Charles Bradlaugh, the atheist politician who had to fight for years to be seated in Parliament.

Although Mill’s views were unpopular, Gladstone once referred to Mill as “the saint of Rationalism.” Mill’s Reform Bill of 1867, the first attempt to grant the vote to British women, while unsuccessful, ignited the British suffrage movement.

Three essays on religion were published posthumously. In them, Mill hints that he had adopted a deistic belief in what he termed a “limited liability god,” surprising his freethinking friends. Mill wrote in Utility of Religion, published in 1874, that belief “in the supernatural … cannot be considered to be any longer required.” He wrote in his Autobiography (1873): “The world would be astonished if it knew how great a proportion of its brightest ornaments — of those most distinguished even in popular estimation for wisdom and virtue — are complete skeptics in religion.” (D. 1873)

"A large proportion of the noblest and most valuable teaching has been the work, not only of men who did not know, but of men who knew and rejected the Christian faith."

— Mill, "On Liberty" (1859)

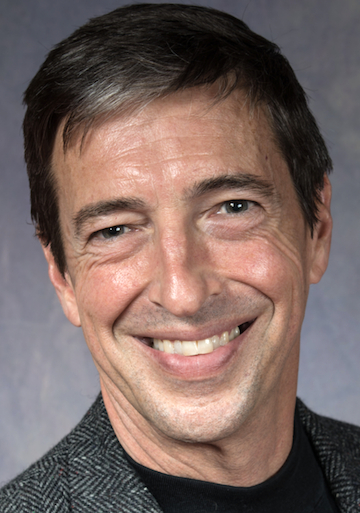

Ron Reagan

On this day in 1958, Ronald Prescott Reagan (Secret Service code name “Reliant”) was born in Los Angeles to Ronald Wilson Reagan and Nancy Reagan, the future U.S. president and first lady. As liberal as his famous father was conservative, Reagan stopped going to church when he was 12 and has publicly stated he’s an atheist numerous times. In 2004, he accepted FFRF’s Emperor Has No Clothes Award and spoke at the 2009 convention in Seattle.

Reagan grew up in Los Angeles and Sacramento, went to Yale University for a semester and then joined the Joffrey Ballet Company as a corps de ballet dancer. He left the Joffrey in 1983 and has since worked as a broadcast and print journalist and television and radio host. He co-hosted “Connected: Coast to Coast with Ron Reagan and Monica Crowley” on MSNBC, was a special correspondent for ABC’s “20/20” and “Good Morning America” and FOX News’ “Front Page,” as well as hosting the syndicated “Ron Reagan Show” starting in 1991.

He’s also done work for E! Entertainment Television, Animal Planet and American Movie Classics and has contributed to Newsweek, The New Yorker, Playboy, Los Angeles Times, Esquire and Interview. “The Ron Reagan Show,” syndicated by Air America Media, went on the air in 2008. Reagan serves on the Advisory Board of the Creative Coalition, a nonpartisan group founded in 1989 to mobilize entertainers and artists for causes such as First Amendment rights, arts advocacy and public education.

Reagan, along with his late mother, has been a strong supporter of embryonic stem cell research. “When you’re depriving people, potentially, of lifesaving or life-improving cures or treatments purely for political reasons, I find that to be really shameful.”

In a 2008 interview with The Hill newspaper, he was asked when he started questioning his father’s political beliefs: “Oh, puberty. Probably by age 12. That was when I told [my parents] I would no longer go to church with them because I was an atheist. One thing leads to another. It wasn’t a great leap to then disagree on politics.” Was he upset? “Yeah, but he wasn’t angry. He was a Christian and took it fairly seriously. He was worried that my life would be diminished if I didn’t accept Christ as my savior. We’d argue at the dinner table all the time, but I don’t think he was losing sleep over it.”

During a speech about stem cell research at the Democratic National Convention on July 27, 2004, Reagan voiced his opinion on church/state separation: “[I]t does not follow that the theology of a few should be allowed to forestall the health and well-being of the many.” The New York Times asked him in 2004, in an interview that ran three weeks after his father died, if he’d like to be president. “I would be unelectable,” Reagan said. “I’m an atheist. As we all know, that is something people won’t accept.”

Reagan, an honorary director of FFRF, generously recorded a radio spot for FFRF during Air America’s broadcast reign, then in 2014 agreed to record a TV ad for FFRF: “Hi, I’m Ron Reagan, an unabashed atheist, and I’m alarmed by the intrusion of religion into our secular government. That’s why I’m asking you to support the Freedom From Religion Foundation, the nation’s largest and most effective association of atheists and agnostics, working to keep state and church separate, just like our Founding Fathers intended. Please support the Freedom From Religion Foundation. Ron Reagan, lifelong atheist, not afraid of burning in hell.”

The ad ran on Comedy Central, CNN and MSNBC’s “Rachel Maddow Show” but was refused by CBS, NBC, ABC and Discovery Networks, apparently due to the irreverent reference to hell. The popularity of the quip has also inspired FFRF to produce a T-shirt, a bumper sticker and a lapel pin saying “Unabashed Atheist, Not Afraid of Burning in Hell,” as well as a personalized online interactive digital “billboard.”

Reagan addressed the FFRF national convention in 2015, where he said: “Blind faith is the abdication of reason. You can’t have a functioning democracy when most of the people believe in a lot of nonsense. If you want good public policy, it has to be based on facts and evidence. Private beliefs invade public policy. All the politicians you see invoking God were just private citizens once, and now they are in Congress.”

In an interview (Jan. 17, 2020) with the Daily Beast after his FFRF ad ran during a Democratic debate, Reagan said he found it curious that people who invoke “freedom of religion really mean freedom to be bigots. ‘Who can we refuse service to?’ It starts with LGBTQ people. What about unmarried couples? What about divorced people? What about black people? You can find justification for almost anything in the Bible, and it’s ugly, cruel, and stupid. We’re on to them. We’ll keep speaking up.”

He married Doria Palmieri in 1980, 20 days after his father was sworn in as president. She died in 2014 at age 62 from complications of a neuromuscular disease. In 2018 he married Federica Basagni, an Italian who was one of Doria’s closest friends.

“As for hell, mocking this imaginary threat rather strikes at the heart of religious belief in a way that I suspect most believers only intuitively grasp. It's a crucial support in their house of cards. Without hell, heaven is pointless.”

— Reagan email statement to FFRF Co-President Annie Laurie Gaylor (April 23, 2019)