November 5

Ella Wheeler Wilcox

On this date in 1850, popular poet Ella Wheeler Wilcox was born in Johnstown in Rock County, Wisconsin. She skyrocketed to fame when a Chicago firm refused to publish a collection of her love poems, calling them immoral. As a result, when Poems of Passion was published in 1883, it sold 60,000 copies in two years. Although well-known for her moral and temperance poems collected in Drops of Water, Wilcox had a theatrical bent, veiled herself in unorthodoxy and enjoyed life as a famous socialite. Her poem “The Queen’s Last Ride,” about attending the funeral of Queen Victoria, launched her fame in Great Britain.

She married Robert Wilcox in 1884 and they lived near Long Island Sound. They both became interested in theosophy and spiritualism and promised each other that whoever died first would return and communicate with the other. Their only child died shortly after birth and Robert died in 1916. Wilcox went to California to consult with a Rosicrucian astrologer to learn why Robert hadn’t contacted her.

Although she practiced Christianity, Wilcox also embraced a somewhat progressive movement called New or Higher Thought and deserves to be considered an honorary freethinker on the strength of her four-line poem “The World’s Need.” She died of cancer at age 68. (D. 1919)

THE WORLD’S NEED

So many gods, so many creeds—

So many paths that wind and wind,

While just the art of being kind

Is all this sad world needs.— Wilcox poem published in The Century quarterly (June 1895)

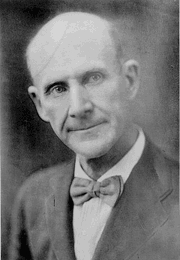

Eugene V. Debs

On this date in 1855, labor leader, reformer and socialist Eugene Victor Debs was born in Terre Haute, Ind. He was not baptized by his formerly Catholic mother. The family living room contained busts of Voltaire and Rousseau. When a teacher gave Debs a bible as an academic award, inscribing it “Read and obey,” Debs later recalled, “I never did either.” (New York Call interviews with David Karsner) He dropped out of high school at age 14 to work.

By 1870 he had become a fireman on the railroad, attending evening classes at a business college. His labor activism began in 1875. As president of the Occidental Literary Club of Terre Haute, Debs brought “the Great Agnostic” Col. Robert Ingersoll, whom he always revered despite political differences, Susan B. Anthony and other famous speakers to town. He was elected to the Indiana General Assembly as a Democrat in 1884 while continuing his labor activities. He married Kate Metzel in 1885. They never had children.

As editor of the Locomotive Fireman’s journal for many years, Debs routinely attacked the church, promoted women’s and racial equality and promoted justice for the poor. “If I were hungry and friendless today, I would rather take my chances with a saloon-keeper than with the average preacher,” Debs once said. (Cited in Eugene V. Debs: A Man Unafraid McAlister Coleman, 1930.) He saved his strongest denunciations for the Catholic Church for being an anti-democratic, authoritarian “political machine.”

Debs organized the first U.S. industrial union, the American Railway Union in Chicago in 1893. It conducted a successful 1894 strike for 18 days against the Great Northern Railway. Debs and leaders of the union were arrested that same year during the Pullman strike and were jailed for contempt of court for six months. Debs ran for president as a Socialist Party candidate in 1900, 1904, 1908, 1912 and 1920.

He was associate editor from 1907-12 of the Appeal to Reason, a popular weekly published by freethinker E. Haldeman-Julius in Girard, Kansas. In 1918 he was arrested for an anti-war speech in Canton, Ohio, and was sentenced under the wartime espionage law to 10 years in prison and loss of citizenship. While in prison he was nominated for president and conducted his last campaign, winning nearly a million votes.

President Warren G. Harding commuted Debs’ sentence and released him on Dec. 25, 1921. He was welcomed by 1,000 Terre Hauteans upon his return. His health broken by his imprisonment, he died at age 70 in a sanitarium. The Terre Haute home he built with his wife in 1890 is a National Historic Landmark of the National Park Service and a museum. (D. 1926)

“I left that church with rich and royal hatred of the priest as a person, and a loathing for the church as an institution, and I vowed that I would never go inside a church again.”

— "Talks with Debs in Terre Haute" by David Karsner (1922)

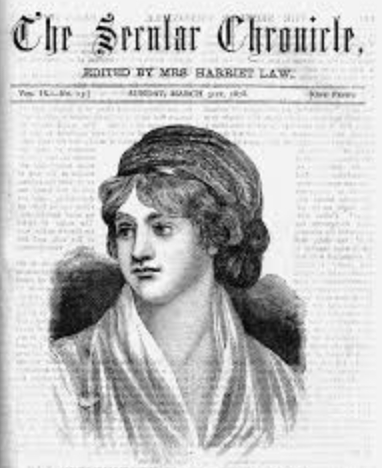

Harriet Law

On this date in 1831, Harriet Teresa Law (née Frost) was born in County Essex, England. The daughter of a small farmer, she was raised as a Calvinist “Strict Baptist” and taught Sunday school. In the 1850s she began debating with freethinkers such as George Holyoake but in the process “saw the light of reason” in 1855 and embraced atheism and feminism and became a salaried speaker for the secularist movement while her husband Edward, also a freethinker, stayed home to care for their four children.

Law was president of the Freethought League in 1869 and was repeatedly elected to (but declined) the position of vice president of the National Secular Society. She bought the Secular Chronicle in 1876 and edited the paper, assisted by her daughter, until 1879. She wrote In her first month as editor, “[T]he Bible does assign women a distinct, and what is worse, a subordinate sphere, rendering her subject to man in nearly every relationship of her life.” She gave the paper a broader scope and published profiles of women freethinkers but sold it because it was losing too much money.

Shortly after that, Law retired from public activities but remained a freethinker until her death. Her early retirement may have been due to ill health but was also partly a result of having been gradually edged out of the movement by Charles Bradlaugh, whose well-known hostility to socialism no doubt added to his already strained relationship with Law. She had also criticized his authoritarian style of leadership.

Eleanor Marx, Karl Marx’s daughter, said Law was one of the first women to recognize “the importance of a woman’s organisation from the proletarian point of view,” adding, “When the history of the labour movement in England is written, the name of Harriet Law will be entered into the golden book of the proletariat.” (Marx, Engels & Lapides, 1990.) She died of a heart attack at age 65 in 1897.

“At the height of her fame as a Secularist, Harriet Law referred to her religious past as evidence of the fact that even the most devoted of Christians could be made to see the light of reason.”

— "Infidel Feminism in Victorian Freethought," lecture by Laura Schwartz, Warwick University (Oct. 13, 2013)

Will Durant

On this date in 1885, William James “Will” Durant was born in North Adams, Mass., one of 11 children born to French-Canadian parents. Durant earned his B.A. from St. Peter’s College in New Jersey in 1907 and his Ph.D. in philosophy from Columbia University in 1917. He was an accomplished historian and philosopher who wrote numerous books, including The Story of Philosophy (1926), but his fame was achieved mainly through the comprehensive 11-volume The Story of Civilization (1927–75), co-written with his wife, Ariel Durant.

The books document the entire history of Western civilization. The Durants were awarded a Pulitzer Prize for General Nonfiction in 1968 for Rosseau and Revolution (volume 10 of The Story of Civilization) and the 1963 Huntington Hartford Foundation Award for Literature for The Age of Louis XIV. Durant wrote numerous other historical and analytical works and three were published posthumously, including Heroes of History (2001) and Fallen Leaves (2014).

Durant was born into a Catholic family and spent seven years at Jesuit schools, including St. Peter’s College and Seminary. Then he lost his faith to the point that he could “no longer think of becoming a priest.” (Quoted in A Dual Autobiography, 1977.) Durant wrote: “By the end of my sophomore year, I had discovered, through Darwin and other infidels, that the difference between man and the gorilla is largely a matter of trousers and words; that Christianity was only one of a hundred religions claiming special access to truth and salvation; and that myths of virgin births, mother goddesses, dying and resurrected deities, had appeared in many pre-Christian faiths, and had helped to transform a lovable Hebrew mystic into the Son of God.”

Before getting his doctorate, he taught at Seton Hall University and at the Ferrer Modern School, where one of his pupils was Chaya (Ida) Kaufman. They married in 1913 when she was 15 and he was 28. He nicknamed her Ariel after the imp in Shakepeare’s “The Tempest” and she later legally changed her name. They had a daughter, Ethel, and raised a foster son, Louis, whose mother was Flora — Ariel’s sister.

The Durants died within two weeks of each other in 1981 and are buried in Los Angeles.

“Does history support a belief in God? If by God we mean not the creative vitality of nature but a supreme being intelligent and benevolent, the answer must be a reluctant negative.”

— Will and Ariel Durant, "The Lessons of History" (1968)

J.B.S. Haldane

On this date in 1892, John Burdon Sanderson Haldane — a scientist who worked in the fields of physiology, genetics, evolutionary biology and mathematics — was born in Oxford, England, to Louisa (née Trotter) and John Scott Haldane, a physiologist and philosopher. Both parents had aristocratic Scottish ancestry. He was raised Episcopalian.

Treated as a miniature adult rather than a child, Haldane proved to be a prodigy, reading by age 3, attending scholarly lectures and assisting his father with experiments. He enrolled at Eton College in 1905, where he became friends with Julian Huxley. Transferring to New College, affiliated with the University of Oxford, he studied mathematics, the classics and genetics, the last of which he is most renowned for. He earned an M.A. in classics from Oxford in 1914.

Serving as a commissioned officer after World War I broke out, he was wounded twice, once so severely he was sent to India to recover. Despite not having an academic degree in the sciences, after the war he was appointed a New College fellow and then did research in physiology and genetics or taught at the University of Cambridge (1922–32), the University of California-Berkeley (1932) and the University of London (1933–57).

Haldane became a Marxist in the 1930s and was London editor of The Daily Worker before becoming disenchanted with communism and leaving the party. He moved to India to head a genetics and biometry lab in 1957, renouncing his British citizenship. He became an Indian citizen in 1961 and worked at the Indian Statistical Institute in Kolkata until his death.

He is regarded as a principal founder of neo-Darwinism, an integration of the theory of evolution by natural selection with Gregor Mendel’s theory of genetics. His major works include “Daedalus, or Science and the Future” (1924), “Animal Biology,” with Julian Huxley (1927), “The Inequality of Man” (1932), “The Causes of Evolution” (1932), “Faith and Fact” (1934), “The Marxist Philosophy and the Sciences” (1938), “Science Advances” (1947) and “The Biochemistry of Genetics” (1954).

In a speech to the Heretics of Cambridge, he read this passage from “Daedalus”: “We must learn not to take traditional morals too seriously. And it is just because even the least dogmatic of religions tends to associate itself with some kind of unalterable moral tradition, that there can be no truce between science and religion.” (Feb. 4, 1923)

Haldane was married twice, first to journalist Charlotte Franken in 1926. They divorced in 1945. Later that year he married Helen Spurway. They met while she was an undergrad at University College London. Twenty-three years his junior, she had earned her Ph.D. in genetics in 1938 under his supervision. Haldane had no children.

He died at age 72 after a long struggle with colo-rectal cancer in Bhubaneswar in eastern India. His skeleton and organs are on display in the Haldane Museum in the pathology department of Rangaraya Medical College. (D. 1964)

“My practice as a scientist is atheistic. That is to say, when I set up an experiment, I assume that no god, angel or devil is going to interfere with its course; and this assumption has been justified by such success as I have achieved in my professional career. I should therefore be intellectually dishonest if I were not also atheistic in the affairs of the world.”

— Haldane in the preface to "Faith And Fact" (1934)