October 27

Michael Servetus (Executed)

On this date in 1553, Spanish physician Michael Servetus, né Miguel Serveto, was executed for heresy in Geneva, Switzerland. Born in 1511, Servetus grew up near Aragon and studied law at the University of Toulouse in France, where he first read the bible, only newly available in printed form. Struck by the absence of mention of the trinity in the bible and repelled by the excesses of the Catholic Church, he turned to Protestantism. Its proponents also cast him out for his views.

In Paris he met a young student, John Calvin, who at one time was forced himself to go into hiding for heresy. Servetus studied medicine at the University of Paris, where he published the first work accurately describing pulmonary circulation. He practiced medicine for 12 years in Vienne, France. In 1546 he started a fateful, heated correspondence on the trinity with Calvin, who wrote a colleague that if Servetus should ever visit Geneva, “if my authority is of any avail I will not suffer him to get out alive.”

Servetus published Christianismi Restitutio (The Restoration of Christianity) under a pseudonym in 1553, including 30 of his letters to Calvin. In it he rejected original sin and salvation, vicarious atonement and Christ’s dual nature. When he sent Calvin a copy, Calvin exposed Servetus’ identity to the Catholic Inquisition in Vienne. Arrested and interrogated, he escaped from prison but was arrested in Geneva while traveling to Italy.

The Protestant Council of Geneva convicted him of anti-trinitarianism and opposition to child baptism. Calvin lobbied for a beheading but the council sentenced him to be burned at the stake, where he was burned alive at age 42 atop a pyre of his own books on Oct. 27, 1553.

“In the Bible, there is no mention of the Trinity.”

— Servetus, "On the Errors of the Trinity" (1531)

Sharlot Hall

On this date in 1870, historian and freethinker Sharlot Mabridth Hall was born in Lincoln County, Kansas. She moved with her family to Arizona at the age of 11. She worked for room and board to attend Prescott High School briefly to escape ranch life but was forced to return home when her mother became ill. Hall took up photography and explored ancient Indian cliff dwellings with her brother. Seeing the lot of women of her era and taking a jaundiced view of the “egotism of the average man,” she vowed never to marry.

When her family attended lectures by freethinker Samuel Putnam in Prescott in 1895, the 24-year old Hall joined him on the platform. She wrote for The Truth Seeker, a major freethought periodical, as well as for many newspapers, and met many leading reformers such as Charlotte Perkins Gilman. Two volumes of Hall’s poetry were published. She began taking oral histories of Arizona pioneers. In 1909, territorial governor Richard Sloan appointed her territorial historian, giving her a Phoenix office.

Supported by the Federation of Women’s Clubs, she traveled throughout Arizona collecting history. After statehood was won, the first governor dismissed her in 1912. After a reclusive retirement caring for family members, she returned to work at age 57 in 1927 when she was given a life lease on the governor’s mansion to restore it as a museum of history in the city of Prescott. The mansion and Sharlot Hall Museum remain open to the public. D. 1943.

With a Box of Apples

Suppose a modern Eve would come

And tempt you with an apple,

Say just about the size of these?

Would you temptation grapple

And manfully declare: ‘I won’t?’

Or, would you say: ‘Well, I

Think since you’ve picked them

They’d be best in dumplings or in a pie.

And, let us ask the serpent in

To share with us at dinner.

A de’il with taste for fruit like that

Can’t be a hopeless sinner.— Sharlot Hall, freethought ditty

Niccolo Paganini

On this date in 1782, violinist Niccolò Paganini was born In Genoa, Italy. He composed his first sonata before the age of 9 and made his first public appearance in 1793. Paginini was appointed first violinist at the Lucca Court, where his diligent application (reportedly practicing up to 15 hours a day as a youth) made him Europe’s foremost virtuoso violinist. Paganini’s acclaimed six-year world tour enthralled audiences with his legendary showmanship, made him wealthy and brought him international celebrity.

He played his own compositions, considered to be so diabolically intricate that the superstitious widely accused him of having made a pact with the devil. Yet his tender passages routinely brought his audience to tears. Paginini retired to his villa in Parma. He lived a religion-free life, refused Catholic sacraments on his deathbed and religious ritual at his burial.

Even his religious biographer, Count Conestabili, admitted Paganini’s “religious indifferentism.” (Vita de Niccolo Paganini, 1851) D. 1840

Klas Pontus Arnoldson

On this date in 1844, Nobel Peace Prize Laureate Klas Pontus Arnoldson was born in Goteburg, Sweden. He left school after his father died at age 16 and worked for the Swedish State Railways for two decades. He was elected to the Riksdag, the Swedish parliament, from 1882-87, where he championed expansion of the franchise, anti-militarism and political neutrality for Sweden. He founded the Swedish Peace and Arbitration Society in 1883 and edited several journals.

He was awarded the Nobel Prize in 1908 for his pacifist work, especially during the 1895 dissolution of the union between Norway and Sweden, in which he controversially sided with Norway. After concentrating on largely journalistic writing, Arnoldson wrote several major works during his last three decades, including Religion in the Light of Research (1891). D. 1916.

“Familiar with the humanistic tenets of religious movements originating in the nineteenth century in Great Britain and in the New England section of the United States, he decried fanatic dogmatism and espoused essentially Unitarian views on truth, tolerance, freedom of the individual conscience, freedom of thought, and human perfectability.”

— from Arnoldson's Nobel Prize biography

Warren Allen Smith

On this date in 1921, Warren Allen Smith was born in Minburn, Iowa. He graduated from Iowa State Teachers College with a B.A. in English in 1948 and received his M.A. in American literature from Columbia University in 1949. During his time in the U.S. Army from 1942-46, Smith was known as “the atheist in a foxhole,” according to his website. He worked as a high school English teacher from 1949-86. In 1961 Smith co-founded the Variety Recording Studio. He lived with his partner of 40 years, Fernando Vargas, an atheist, until Vargas’ death from AIDS in 1989.

Smith’s fame stemmed from his journalism, which often touched on humanist issues. He was book review editor for The Humanist from 1953-58 and wrote the column “Humanist Potpourri” for Free Inquiry from 1997-98, as well as writing columns for Gay and Lesbian Humanist, The Freethinker, The American Rationalist and Skeptical Inquirer. He wrote the books Who’s Who in Hell: A Handbook and International Directory for Freethinkers, Humanists, Naturalists, Rationalists, and Non-Theists (2000) and Celebrities in Hell (2002), which are extensive compilations of famous freethinkers. Smith’s other books include Gossip from Across the Pond (2005) and In the Heart of Showbiz (2011).

Smith rejected his Methodist upbringing during college. In a 2000 article for The New York Observer, he wrote, “If you’re the member of an organized church group, you really have to have a guilt complex. You have to feel guilty about not loving God enough or not contributing enough money or not contributing enough to society.” He described himself as a “humanistic naturalist” in his book Who’s Who in Hell. Smith’s other accomplishments included serving as as vice president of the Bertrand Russell Society from 1977-80, treasurer of the Secular Humanist Society of New York from 1988-93 and co-founding Agnostics, Atheists, and Secular Humanists Who Are Infected/Affected with AIDS/HIV Illness in 1992 (although Smith himself was not HIV-positive). He created Philosopedia, an online reference for philosophers and atheists. (D. 2017)

“Were there atheists in foxholes during World War II? Of course, as can be verified by my dogtags. … A veteran of Omaha Beach in 1944, I insisted upon including ‘None’ instead of P, C, or J as my religious affiliation.”

— W.A. Smith, Freethought Today (November 1997)

William Maclure

On this date in 1763, William Maclure, now known as the “Father of American Geology,” was born to a wealthy family in Ayr, Scotland. He visited the United States as a teenager, made a fortune in the import-export business in London and became a U.S. citizen in 1796, where he conducted studies that eventually became the U.S Geological Survey. Maclure’s map, the first widely available geologic map, was published in 1809 as part of the paper Observations on the Geology of the United States. He was president of the Academy of Natural Sciences of Philadelphia (1817–37).

In 1824, along with social reformer Robert Owen, Maclure established a short-lived utopian community in New Harmony, Indiana. In 1838 he founded the first free public library in Indiana, the New Harmony Workingmen’s Institute. Maclure lived in Mexico from 1827 until his death 13 years later at age 76.

He became critical of formal religion early in life due to his experience with the Calvinist Church of Scotland, which taught that everyone was inherently sinful. He called religion a “delusion” and said there was “nothing beyond the grave.” (Maclure of New Harmony: Scientist, Progressive Educator, Radical Philanthropist by Leonard Warren.) He was disdainful of the clergy: “The priests have retained their consideration and labor hard in their calling for the propagation of ignorance, superstition, and hypocracy [sic],” Maclure wrote in his journal while visiting France in 1807. (D. 1840)

“We shall be astonished at the long continuance of the delusion that has led the human intellect astray, through the mysterious wilderness of deception, by the cunning intrigues of church and State.”

— William Maclure, quoted in "Opinions on various subjects: dedicated to the industrious producers, Vol. 1" (1831)

Sylvia Plath

On this date in 1932, Pulitzer Prize-winning poet Sylvia Plath was born in Boston to Otto and Aurelia Plath. A writer at the forefront of the 1950s movement known as “confessional poetry,” Plath’s published collections include The Colossus and Other Poems (1960), Ariel (1965) and The Collected Poems (1974), along with the semi-autobiographical and widely read novel The Bell Jar (1963), published shortly before her death at 30.

Ariel and The Collected Poems were published posthumously, the latter edited by Plath’s husband, the English poet Ted Hughes. The Collected Poems was awarded the Pulitzer Prize for Poetry in 1982. Plath’s poetry — often cited for its violence, precision, preoccupation with death and autobiographical nature — also explored the elemental forces of nature, religion, mental illness and the struggles surrounding femininity. The writer Joyce Carol Oates once described Plath as “one of the most celebrated and controversial of post-war poets writing in English.”

In The Bell Jar, Plath describes her father as “a bitter atheist.” He had been ostracized by his German family for his refusal to become a Lutheran minister. Likewise, Plath’s mother left the Catholic Church in college, citing its “repressive and controlling ideology.” (Sylvia Plath: A Biography, 1987.) Plath herself attended a Unitarian church, where she led the youth group. In college she often wrote about her struggles with religion. In a paper written for Introduction to the Study of Religion, she denied the existence of God and of an innate human consciousness.

After marrying Hughes in 1956, the couple moved to the U.S. and Smith taught at Smith College, her alma mater. Because she wanted more time to write, she left Smith after a year and took a job as a receptionist in the psychiatric unit of Massachusetts General Hospital. She sat in on evening creative writing seminars given by poet Robert Lowell. Her daughter Frieda was born in 1960, followed by a son, Nicholas, in 1962.

As far back as 1953 she had attempted suicide with pills. In 1962 she drove her car off the road into a river. That same year she discovered Hughes had been having an affair with Assia Wevill and they separated. Plath was found dead of carbon monoxide poisoning with her head in the oven on Feb. 11, 1963. She had sealed the rooms between her and her sleeping children with tape, towels and cloths. Nicholas Hughes hanged himself at age 47 in Fairbanks, Alaska, where he had earned a Ph.D. in biology and was working at the University of Alaska. (D. 1963)

“I don’t believe in God as a kind father in the sky. I don’t believe that the meek will inherit the earth: The meek get ignored and trampled.”

— "The Unabridged Journals of Sylvia Plath: 1950-1962"

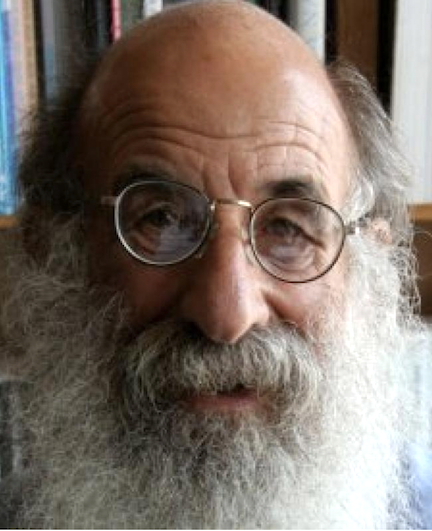

Malcolm Margolin

On this date in 1940, author and publisher Malcolm Margolin was born in Boston to a Lithuania-born homemaker and an American father and was raised in an Orthodox Jewish home. He attended the Boston Latin School and Harvard College, majoring in English.

After graduation, two years in Puerto Rico and a trip to San Francisco during the 1967 Summer of Love, he and his wife Rina moved to the West Coast for good. They eventually settled in Berkeley, Calif., and Margolin wrote for such publications as Science Digest and The Nation.

He was working for the park district on trail maintenance when he started to get book contracts for volumes on parks, ecology and Native Americans. He founded Heyday Books, an independent nonprofit publisher, in 1974. Where did the name come from?

They had named their son Reuben Heyday “because that’s just what hippies did,” Margolin said. He liked “Reuben” for its old Jewish sense and “Heyday” because it had a sense of celebration and wonderment. (San Francisco Examiner, Jan. 18, 2015) When it came time to name his small company, he picked Heyday as a placeholder, a name still in place. (The Margolins named their daughter Sadie Cash and their other son Jacob Orion.)

In 1978 he published The Ohlone Way: Indian Life in the San Francisco-Monterey Bay Area, now a classic. “Before the coming of the Spaniards, Central California had the densest Indian population anywhere north of Mexico,” according to its introduction.

Margolin retired in 2016 as publisher, and the company by 2020 was publishing about 20 books a year. “Heyday promotes civic engagement and social justice, celebrates nature’s beauty, supports California Indian cultural renewal, and explores the state’s rich history, culture, and influence,” said its website. Heyday has published Pulitzer Prize-winning authors Gary Snyder and Wallace Stegner, Rebecca Solnit, former U.S. Poet Laureate Robert Hass and Ursula Le Guin, the fantasy and science fiction writer.

In a 2016 interview with The Jewish News of Northern California, Margolin said his Orthodox upbringing gave him a sense of scholarship and entrepreneurialism along with a distrust of institutions. “Today, I have no religious beliefs whatsoever, but I don’t eat pork.”

“I’m not religious. I’m not superstitious. I don’t believe in any of this stuff.”

— Interview, Oral History Center, Bancroft Library, University of California-Berkeley (March 22, 2013)

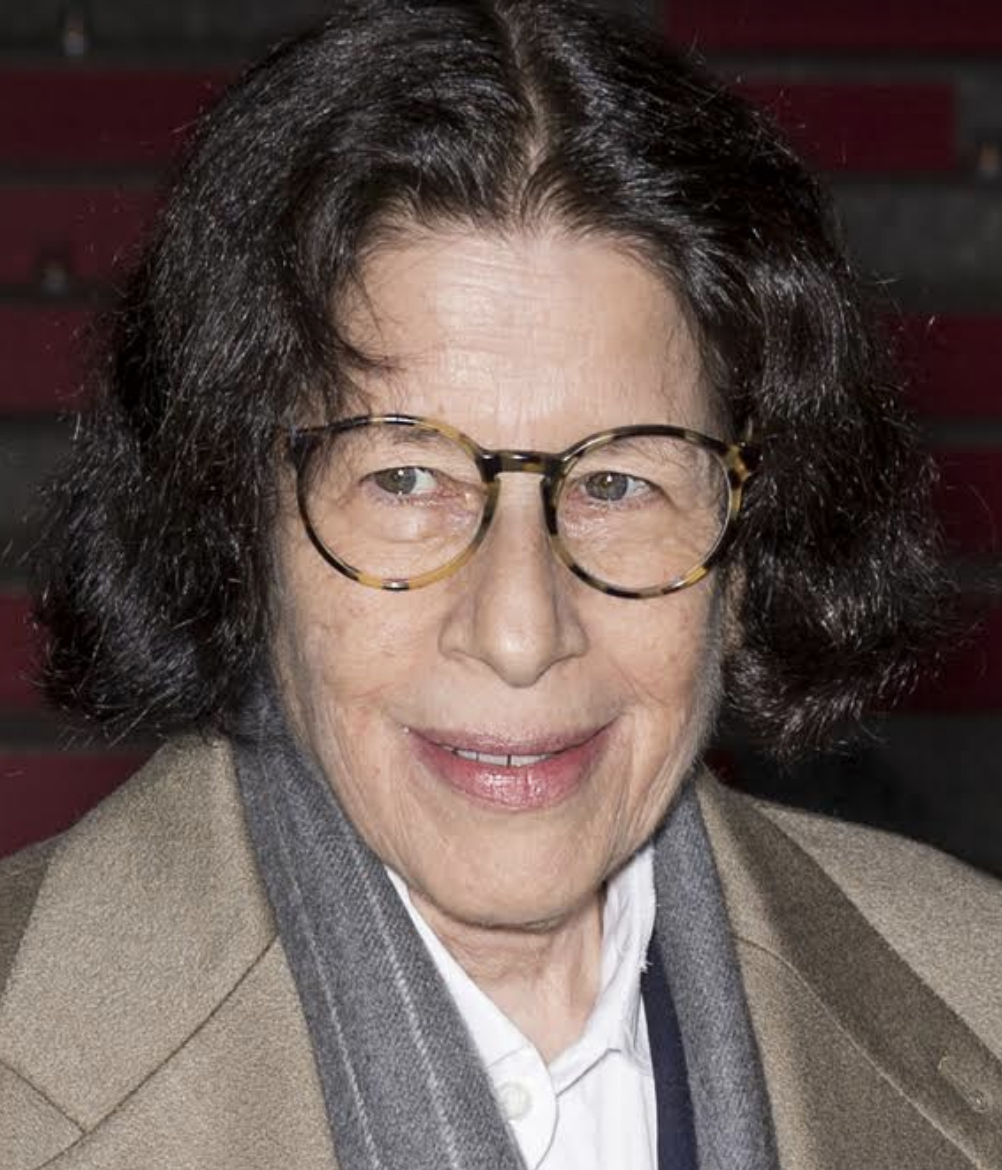

Fran Lebowitz

On this date in 1950, author and humorist Frances Ann Lebowitz was born in Morristown, N.J., to Ruth and Harold Lebowitz, who owned a furniture store and upholstery shop and attended a Conservative Jewish synagogue. She was expelled from an Episcopalian high school at age 17 for what she later called “non-specific surliness” and completed her GED.

She moved to New York City in 1969 and worked as a cleaning lady, chauffeur, taxi driver and freelance writer. Andy Warhol hired her as a columnist for Interview magazine. She also wrote for Mademoiselle. Her first book, a collection of comedic essays titled Metropolitan Life, was published in 1978.

“All God’s children are not beautiful. Most of God’s children are, in fact, barely presentable,” Lebowitz wrote in Social Studies (1981), another essay collection. The Fran Lebowitz Reader and the children’s book Mr. Chas and Lisa Sue Meet the Pandas followed in 1994.

Since then she has worked on uncompleted book projects like Exterior Signs of Wealth — a novel about rich people who want to be artists and artists who want to be rich — and her book Progress, excerpted in Vanity Fair starting in 2004 but still unfinished as of 2021. “For every mandatory moment of silence before classes at a public school, during which students are free to pray or not, there will be a mandatory moment of noise before services at a religious institution, during which congregants are free to listen or not.” (Vanity Fair, Oct. 17, 2006)

Lebowitz later largely supported herself with TV appearances, speaking engagements and as a contributing editor and occasional columnist for Vanity Fair. She is a political liberal and a lesbian who is uncomfortable in long-term relationships. “I’m the world’s greatest daughter. I’m a great relative. I believe I’m a great friend. I’m a horrible girlfriend. I always was. I’m great at the beginning, because I can be very romantic.” (Interview magazine, March 11, 2016)

She was the subject of film director Martin Scorsese’s 82-minute documentary “Public Speaking” on HBO in 2010 before a limited theatrical release the next year. She collaborated again with Scorsese on “Pretend It’s a City,” a seven-part documentary series featuring her interviews and conversations with Scorsese. It was released on Netflix in January 2021.

“I got in trouble when I was 12 or 13, because I told the Sunday school teacher I don’t believe in God. I have not changed my mind on that,” Lebowitz once told an interviewer. “My Jewish identity is ethnic or cultural or whatever people call it now. But it’s not religious.” (New Jersey Jewish News, Jan. 27, 2016)

PHOTO: Lebowitz at the 2015 Tribeca Film Festival in New York City; Ovidiu Hrubaru / Shutterstock.com

“I’ve been an atheist since I was about 7 years old.”

— Haaretz interview (Oct. 6, 2011)