November 18

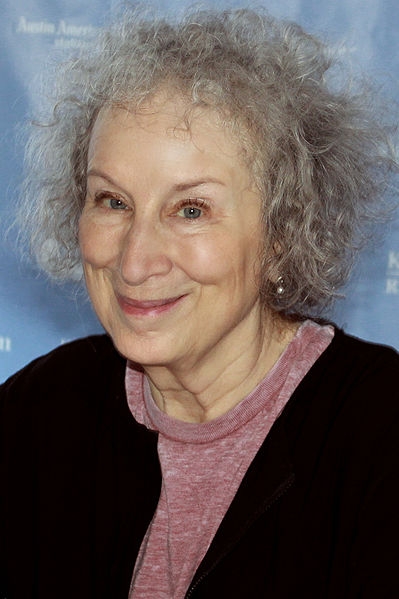

Margaret Atwood

On this date in 1939, novelist and poet Margaret Atwood was born in Ottawa, Canada. As a youngster, she spent many months of each year in the wilderness with her parents, due to her father’s job as a forest entomologist. Atwood, fittingly, was descended from Mary Webster, accused of witchcraft in Salem, Mass., and sentenced to be hanged in 1685 but allowed to live after the rope broke. Atwood made her ancestor the subject of her poem “Half-Hanged Mary.”

Atwood earned a B.A. from the University of Toronto in 1961, her M.A. from Radcliffe College and attended Harvard for two years of postgraduate study. She held a variety of positions at various colleges and has been published in 14 volumes of poetry, including Margaret Atwood Poems (1965-1975), published in 1991.

Her novels include Edible Woman (1969), Surfacing (1972), Lady Oracle (1976), Life Before Man (1979), Bodily Harm (1981), The Handmaid’s Tale (1985), Cat’s Eye (1988), The Robber Bride (1993), Alias Grace (1996), The Blind Assassin (2000), Oryx and Crake (2003), the first novel in a series that also includes The Year of The Flood (2009) and MaddAddam (2013), which would collectively come to be known as the MaddAddam Trilogy.

The Handmaid’s Tale, about a theocratic takeover of the United States, inspired the 1990 movie adapted by Harold Pinter. Atwood published Hag-Seed, a modern-day retelling of Shakespeare’s “The Tempest,” in 2016. Her 2019 novel The Testaments, a sequel to The Handmaid’s Tale, was a Booker Prize finalist.

She has called herself an agnostic: “A doctrinaire agnostic is different from someone who doesn’t know what they believe. A doctrinaire agnostic believes quite passionately that there are certain things that you cannot know, and therefore ought not to make pronouncements about. In other words, the only things you can call knowledge are things that can be scientifically tested.” (Quoted in Humanism as the Next Step by Lloyd and Mary Morain, 1954)

She was named Canadian Humanist of the Year in 1987 and the American Humanist Association’s 1987 Humanist of the Year. She married American writer Jim Polk in 1968. They divorced in 1973 and she formed a relationship with novelist Graeme Gibson. They moved to a farm near Alliston, Ontario, where their daughter Eleanor Jess Atwood Gibson was born in 1976.

PHOTO: Atwood at the Texas Book Festival in Austin in 2015; photo by Larry D. Moore under CC BY 4.0.

“This is not an attack on Christianity, but the fact is Christians have long persecuted other sects and each other, as they are in Northern Ireland today. People were saying things like, ‘A woman’s place is in the home.’ And I got to thinking, well, how would someone enforce thoughts like that?”

— Atwood, on writing "The Handmaid's Tale," New York Times interview (April 14, 1990)

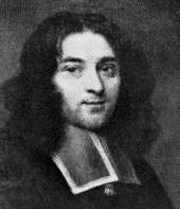

Pierre Bayle

On this date in 1647, Enlightenment skeptic Pierre Bayle, was born in southern France. He was the son of a Protestant minister at a time when Huguenots endured severe persecution. He was therefore educated at a Jesuit college in Toulouse. Under pressure he dallied with a conversion to Catholicism but ultimately rejected it, thereby becoming a “relaps” under French law — a person who becomes a heretic after abjuring heresy and subject to punishment.

Bayle decided it was safer to study philosophy in Calvinist Geneva. He became professor of philosophy in 1675 at a Protestant academy in Sedan until it was closed down by Catholic authorities in 1681. Bayle joined the community of French Protestant refugees in Rotterdam, where he taught. Bayle published a 1682 paper on a comet, including the comment, “No nations are more warlike than those which profess Christianity.”

He edited one of the first academic journals, Nouvelles de la republique des lettres (1684-87), and made rejection of superstition and intolerance a centerpiece of his writings. His masterpiece was a philosophical analysis of the words of Jesus: “Constrain them to come in.” Bayle protested conversion by force, and was the first to argue for complete religious toleration and freedom of conscience, including for Jews, Muslims and atheists.

His writings were collected in The Historical and Critical Dictionary, published in Rotterdam in 1692 and translated into English in 1736. While successful, his dictionary was banned in France and even condemned by the Huguenots. Bayle updated it to answer attacks, writing that no religious beliefs were supported by reason. Voltaire later called it “the Arsenal of the Enlightenment.” Bayle never left his Calvinist church, though many friends, future freethinkers and nearly all his critics regarded him as a “secret atheist.” He died in Rotterdam at age 59. (D. 1706)

“It is pure illusion to think that an opinion which passes down from century to century to century, from generation to generation, may not be entirely false.”

— Bayle, "Thoughts on the Comet" (1682)

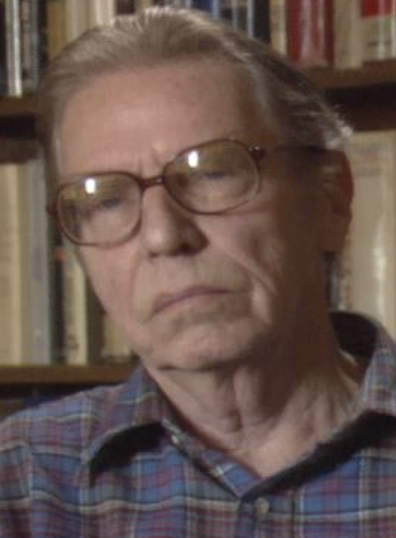

Chalmers Roberts

On this date in 1910, Chalmers Roberts was born in Pittsburgh, Pa. He earned a degree from Amherst College in 1933 and later became a journalist for seven newspapers, including the Japan Times in Tokyo in 1938 and the Washington Post in 1949. Roberts was chief diplomatic correspondent of the Post from 1953-71, often with front-page bylines.

He wrote influential articles about the Pentagon Papers, the secret government documents detailing deceptions during the Vietnam War, and was named as a defendant in the case that made it to the U.S. Supreme Court for publishing the documents.

Roberts continued to write columns for the Post until 2004. He wrote five books, including Washington Past and Present (1950), The Nuclear Years: The Arms Race and Arms Control (1970) and his autobiography, First Rough Draft: A Journalist’s Journal of Our Times (1973). In 1941 he married Lois Roberts, who died in 2001. They had three children: David, Patricia and Christopher.

After being diagnosed with congestive heart failure, Roberts chose to refuse potentially lifesaving open-heart surgery. He wrote about his decision in the Post on Aug. 28, 2004, explaining his views on religion and the afterlife: “I agree with Francis Crick, the eminent Cambridge don, the winner of the Nobel Prize for his co-discovery of the double helix, the blueprint of life, who wrote: ‘In the fullness of time, educated people will believe there is no soul independent of the body, and hence no life after death.’ ”

He died at age 94 in Bethesda, Md. (D. 2005)

“I do want to add a final word about the hereafter. I do not believe in it. I think that the religions which promise various after-life scenarios basically invented them to meet the longing for an answer to life’s mysteries.”

— Roberts, the Washington Post (Aug. 28, 2004)

Ben Winter

On this date in 1927, author and cowboy Bennie Nyles “Ben” Winter was born in Fox, Okla., second child of Charles and Hazel Winter. Growing up on a farm, he enjoyed roping cows and horseback riding. A quote above his rural elementary school entryway stuck with him, a catalyst for a lifetime love of learning and friendly debate: “Knowledge Once Gained Casts a Light Beyond its Own Immediate Boundaries.” Winter joined the Air Force in his late teens and worked in a print shop on Okinawa during the Korean War.

In 1949 he “stole” an Air Force buddy’s photo of a beautiful woman, Joyce Lynn Sadler, from Homer, Okla., whom he married that year. They had five children: Schahara Suzanne, Scheryl Sharisse, Scharmagne Suzette, Christopher Thomas and Schaunon Simone.

An entrepreneur at heart, even while employed in the oilfield, Winter was a successful horse breeder, trainer and racehorse owner with many visits to the winner’s circle. A self-taught artist and musician, he wrote many poems and stories, including the nonfiction The Great Deception: Symbols & Numbers Clarified. Over 13 years, he researched Josephus, the Christian bible, Strong’s Concordance and hundreds of other works.

He had been exposed to conventional biblical teachings, raised mostly in the Church of Christ: “What I was reading in the bible and what I was hearing from the pulpit did not coincide. When contemplating meaning, modern clergy and bible students subscribe to emotion rather than scholarly endeavor of which these ancient symbols resisted first century as well as modern interpretation.”

Winter died at the Ardmore Veterans Home on Sept. 5, 2018. Joyce, his wife of nearly 70 years, died in April 2019.

“Belief is an anomaly of the mind.”

— Ben Winter