presidents

‘Wall of Separation’ Phrase Coined

On this date in 1802, President Thomas Jefferson coined the famous phrase describing the Establishment Clause of the First Amendment as erecting “a wall of separation between church and state.” He used the phrase in his famous letter to the Baptists of Danbury, Connecticut, who had asked him to explain the meaning of the First Amendment’s phrase “Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion.”

“I contemplate with sovereign reverence that act of the whole American people which declared that their legislature should make no law respecting an establishment of religion, or prohibit the free exercise thereof, thus building a wall of separation between church and state.”

— Jefferson's letter to the Baptists of Danbury (Jan. 1, 1802)

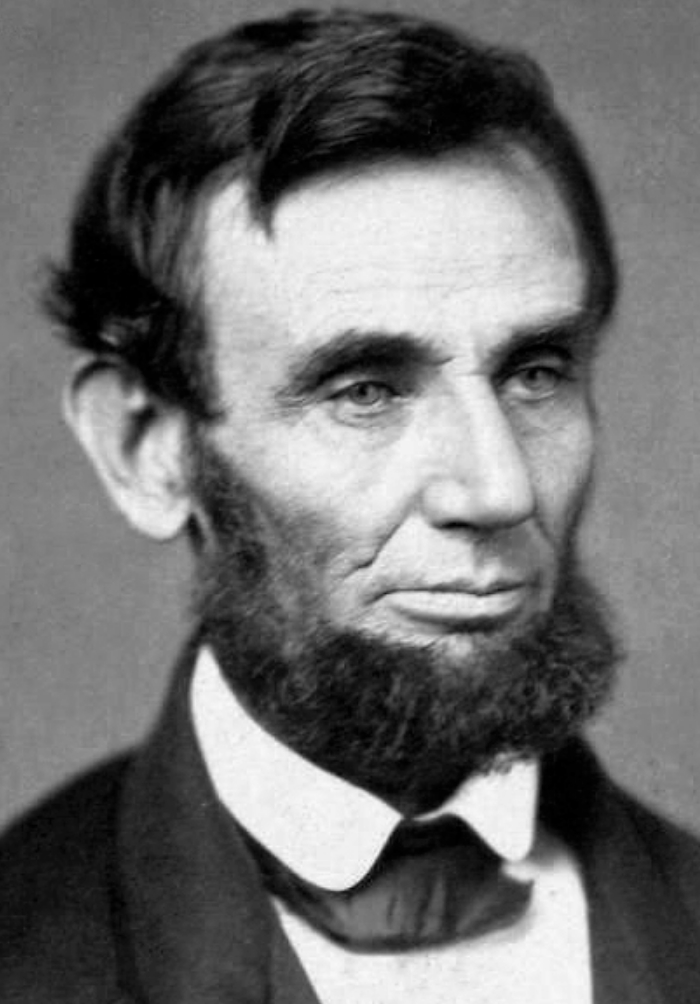

Abraham Lincoln

On this date in 1809, the 16th U.S. president, Abraham Lincoln, was born in Hardin County, Kentucky. Largely self-educated, he worked on farms, splitting those famous rails, and clerking at a store. Lincoln spent eight years in the Illinois Legislature and also rode the circuit of courts for many years. He married Mary Todd; only one of their four sons lived to adulthood. While seeking the nomination for Congress, Lincoln ruefully wrote Martin M. Morris, of Petersburg, Illinois, that “There was the strangest combination of church influence against me .. everywhere contended that no Christian ought to vote for me because I belonged to no Church, [and] was suspected of being a Deist.” (March 26, 1843, Complete Works of Abraham Lincoln, Nicolay & Hay edition.)

Lincoln ran against Stephen A. Douglass for U.S. senator in 1858, losing the election but winning a national reputation. Elected as a Republican as president in 1860, Lincoln guided the nation during the Civil War, issuing the Emancipation Proclamation on Jan. 1, 1863, which freed slaves within the Confederacy. He won reelection in 1864. His wise plans for peace (“With malice toward none; with charity for all”) were foiled by an assassin’s bullet on April 14, 1865, at Ford’s Theatre in Washington, D.C.

Among the words inscribed at the Lincoln Memorial are Lincoln’s Second Inaugural address, which, though full of conventional references to the “Almighty,” astutely observes of the North and the South: “Both read the same Bible and pray to the same God, and each invokes His aid against the other. It may seem strange that any men should dare to ask a just God’s assistance in wringing their bread from the sweat of other men’s faces, but let us judge not, that we be not judged.”

While Lincoln punctuated his eloquent speeches with deistic references to “Divine Providence,” in which he firmly believed, he was strongly rationalist and not conventionally Christian. Among the friends who testified to that was Ward Hill Lamon in Life of Abraham Lincoln (1872). Lamon, who was religious, had known Lincoln for years and wrote: “Perhaps no phrase of his character has been more persistently misrepresented and variously misunderstood than this of his religious belief.”

Lamon related how Lincoln wrote a “little book,” probably an extended essay, to prove “First, that the Bible is not God’s revelation. Second, that Jesus was not the Son of God.” He took the manuscript to Samuel Hill, a shopkeeper and unbeliever, whose son considered the work “infamous.” Hill reportedly snatched the book from Lincoln and threw it into the fire to protect Lincoln’s political career, a story other contemporaries corroborated had been told them.

“But he never told anyone that he accepted Jesus as the Christ,” Lamon noted. His book also quotes Lincoln’s first law partner, John T. Stuart: “Lincoln went further against Christian beliefs and doctrines and principles than any man I ever heard: he shocked me.” David Davis, who knew Lincoln for 20 years and rode with him on the court circuit, told Lamon: “He had no faith, in the Christian sense of the term.” (D. 1865)

PHOTO: Lincoln on Nov. 8, 1863, 11 days before the Gettysburg Address; photo by Alexander Gardner.

“Mr. Lincoln was never a member of any Church, nor did he believe in the divinity of Christ, or the inspiration of the Scriptures in the sense understood by evangelical Christians.”

“When a boy, he showed no sign of that piety which his many biographers ascribe to his manhood. When he went to church at all, he went to mock, and came away to mimic.”

“When he came to New Salem, he consorted with Freethinkers, joined with them in deriding the gospel story of Jesus, read Volney and Paine, and then wrote a deliberate and labored essay, wherein he reached conclusions similar to theirs.”

— "The Life of Abraham Lincoln" by Ward H. Lamon (1872)

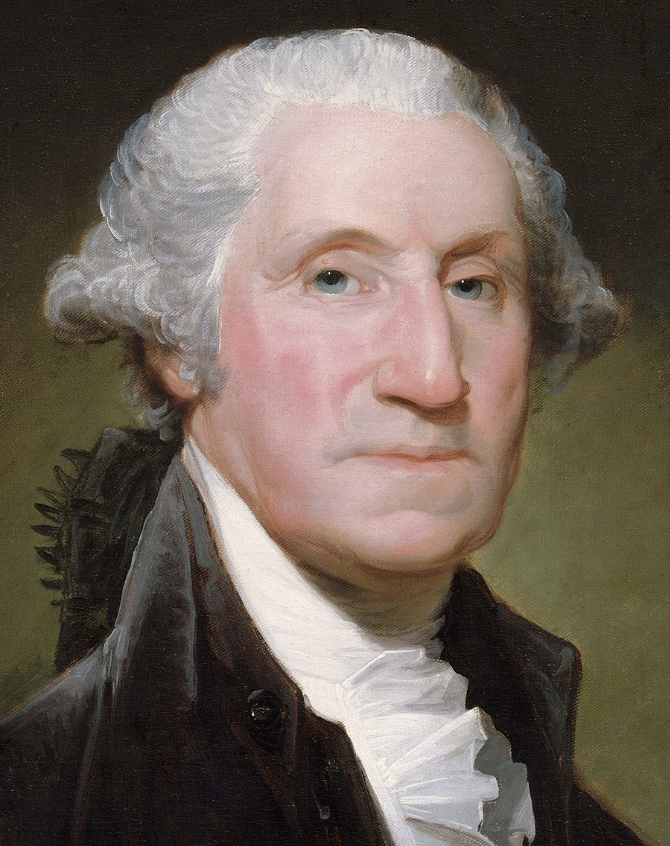

George Washington

On this date in 1732, George Washington was born in Popes Creek, Va., the eldest of six children. His father died when he was 11 and Washington inherited 10 slaves and a farm. He received a surveyor’s license in 1749 from the College of William & Mary and was appointed surveyor of Culpeper County. By 1752 he owned 2,315 acres of land.

Washington was elected to the Virginia House of Burgesses in 1758, was a delegate to the Continental Congress of 1774 and became commander of the Continental Army in 1775. He presided over the Constitutional Convention in Philadelphia in 1787, which adopted a godless constitution, and was elected the first U.S. president in 1789. He was reelected in 1793 and retired to Mount Vernon at the end of his second term. He married Martha Dandridge Custis in 1759 after her husband died when she was 25. Washington adopted her two children; two others had died.

Thought by many to be a deist, Washington has been claimed by many religions but kept his beliefs mostly to himself: “Religious controversies are always productive of more acrimony & irreconcilable hatreds than those which spring from any other source.” (Washington letter to Sir Edward Newenham, June 22, 1792.)

Jefferson recorded this on Feb. 1, 1800, in Memoir, Correspondence, And Miscellanies, From The Papers Of Thomas Jefferson, Vol. 4: “Doctor Rush tells me that he had it from Asa Green, that when the clergy addressed General Washington on his departure from the government, it was observed in their consultation, that he had never, on any occasion, said a word to the public which showed a belief in the Christian religion, and they thought they should so pen their address, as to force him at length to declare publicly whether he was a Christian or not. They did so. However, he observed, the old fox was too cunning for them. He answered every article of their address particularly except that, which he passed over without notice. Rush observes, he never did say a word on the subject in any of his public papers, except in his valedictory letter to the Governors of the States when he resigned his commission in the army, wherein he speaks of ‘the benign influence of the Christian religion.’ I know that Gouverneur Morris, who pretended to be in his secrets and believed himself to be so, has often told me that General Washington believed no more of that system than he himself did.”

The foremost mythmaker about Washington was Parson Mason Weems, whose Life of Washington (1800) promoted the cherry tree story and other disinformation, such as the claim that Washington prayed in the woods at Valley Forge in the Revolutionary War winter of 1777-78.

Propagandists allege Washington wrote a Christian prayer, which is engraved on a bronze tablet at St. Paul’s Chapel in New York City. The source is not a prayer, but a business letter to governors, which makes two orthodox, deistic references (The Writings of George Washington, ed. Worthington Ford, 1889). Washington’s diaries reveal that he seldom attended church and often traveled on the sabbath. (D. 1799)

PHOTO: Washington in 1795 in an oil painting by Gilbert Stuart (cropped).

“Of all the animosities which have existed among mankind, those which are caused by difference of sentiment in religion appear to be the most inveterate and distressing, and ought most to be deprecated. I was in hopes that the enlightened and liberal policy which has marked the present age would at least have reconciled Christians of every denomination, so far that we should never again see their religious disputes carried to such a pitch as to endanger the peace of society.”

— Washington letter to Edward Newenham, June 22, 1792, "The Writings of George Washington, Vol. XII"

James Madison

On this date in 1751, James Madison Jr. was born near Port Conway, Va., to James and Nelly Conway Madison. A deist, he became the primary author of the secular U.S. Constitution and Bill of Rights and the fourth U.S. president. Madison was elected to the first House of Representatives, was secretary of state under Thomas Jefferson and served as president from 1809 to 1817.

Baptized Anglican, he contemplated the ministry as a career. After graduating from the College of New Jersey (later renamed Princeton), Madison was appointed a delegate to the Virginia state convention. There he was responsible for the adoption of a freedom of conscience clause in the state constitution. “Religious bondage shackles and debilitates the mind and unfits it for every noble enterprise, every expanded prospect,” Madison wrote William Bradford on April 1, 1771.

After being elected to the Virginia Legislature, his famous “Memorial and Remonstrance” defeated a bid to force mandatory tithing in 1785. In it, he stated “it is proper to take alarm at the first experiment on our liberties.”

“During almost fifteen centuries has the legal establishment of Christianity been on trial. What have been its fruits? More or less in all places, pride and indolence in the Clergy, ignorance and servility in the laity, in both, superstition, bigotry and persecution.” (Memorial and Remonstrance Against Religious Assessments, June 20, 1785)

His “Detached Memorabilia,” written between 1817 and 1832, revealed his regrets over the appointment of chaplains to the two houses of Congress. Madison called it “a palpable violation of equal rights, as well as of Constitutional principles.” He equally argued against chaplains in the military and religious proclamations by the president, writing that such acts “imply a religious agency.”

In a letter to Louisiana attorney and legislator Edward Livingston, Madison wrote: “Every new & successful example therefore of a perfect separation between ecclesiastical & Civil matters is of importance. And I have no doubt that every new example will succeed, as every past one has done, in shewing that Religion & Govt. will both exist in greater purity, the less they are mixed together.” (July 10, 1822)

Madison married Dolley Payne Todd, a widow and 17 years his junior, in 1794, helping raise her son Payne. In 1826, after Jefferson’s death, Madison was appointed as rector of the University of Virginia. He retained the position as college chancellor for 10 years until his death at Montpelier at age 85 of congestive heart failure. (D. 1836)

“[T]he number, the industry, and the morality of the priesthood & the devotion of the people have been manifestly increased by the total separation of the Church from the State.”

— "The Writings of James Madison, Vol. VIII: 1808-1819," ed. Gaillard Hunt (1908)

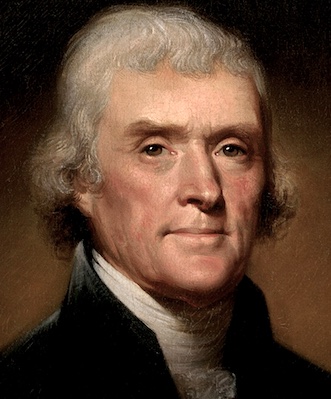

Thomas Jefferson

On this date in 1743, Thomas Jefferson, who became the third U.S. president, was born in Virginia. As a young attorney and member of the Continental Congress, Jefferson drafted the Declaration of Independence. Jefferson became governor of Virginia in 1779, when the Anglican Church was disestablished as the state religion.

He wrote the Virginia Statute of Religious Freedom, whose preamble indicted state religion, noting that “false religions over the greatest part of the world and through all time” have been maintained through the church-state. The heart of the statute guarantees that no citizen “shall be compelled to frequent or support any religious worship, place, or ministry whatsoever.” It was adopted in 1786 and is replicated in most other state constitutions.

Jefferson spent five years in France as an ambassador, and therefore was out of the country at the time of adoption of the U.S. Constitution. He strenuously urged the addition of a Bill of Rights. He became the first secretary of state in 1789, vice president in 1796, president in 1800 and was reelected in 1804.

In his Notes on Virginia (1781), Jefferson, a Deist, wrote: “Millions of innocent men, women and children since the introduction of Christianity have been burnt, tortured, fined, imprisoned. Yet have we not advanced one inch towards uniformity. What has been the effect of coercion? To make one half the world fools and the other half hypocrites. To support roguery and error all over the earth.”

He contemptuously rejected the holy trinity concept, regarded Jesus as a human teacher only and in 1804 composed a 46-page New Testament extraction titled The Philosophy of Jesus of Nazareth. In an October 1813 letter to John Adams, he wrote: “I have performed this operation for my own use, by cutting verse by verse out of the printed book, and arranging the matter which is evidently his, and which is as easily distinguishable as diamonds in a dunghill.” In 1820 he produced what became known as the Jefferson Bible, 84 pages. It was titled The Life and Morals of Jesus of Nazareth.

As president he issued his famous letter to the Baptists of Danbury, Connecticut, on Jan. 1, 1802, explaining that the Establishment Clause of the First Amendment builds “a wall of separation between church and state.” He refused to issue any days of prayer or thanksgiving, believing civil powers alone were conferred on public officials.

Jefferson owned about 600 slaves during his lifetime, some inherited. The highest slave population at his Monticello estate, in 1817, was 140. While some aspects of his ownership were seen as benevolent for the times, not everyone agreed. Virginia abolitionist Moncure Conway, born six years after Jefferson’s death, remarked that his reputation as an emancipator was undeserved: “Never did a man achieve more fame for what he did not do.” (Smithsonian Magazine, October 2012)

Jefferson instructed that the epitaph on his tombstone read: ” ‘Author of the Declaration of American Independence, of the Statute of Virginia for Religious Freedom & Father of the University of Virginia,’ because by these, as testimonials that I have lived I wish most to be remembered.” He and former President John Adams both died on the 50th anniversary of the July 4 adoption of the Declaration of Independence. (D. 1826)

IMAGE: Oil portrait of Jefferson by Rembrandt Peale, 1800.

“Question with boldness even the existence of a God; because, if there be one, he must more approve of the homage of reason than that of blindfolded fear. … Do not be frightened from this inquiry by any fear of its consequences. If it ends in a belief that there is no God, you will find inducements to virtue in the comfort and pleasantness you feel in its exercise, and the love of others which it will procure you.”

— Jefferson's letter to nephew Peter Carr, written from Paris (Aug. 10, 1787)

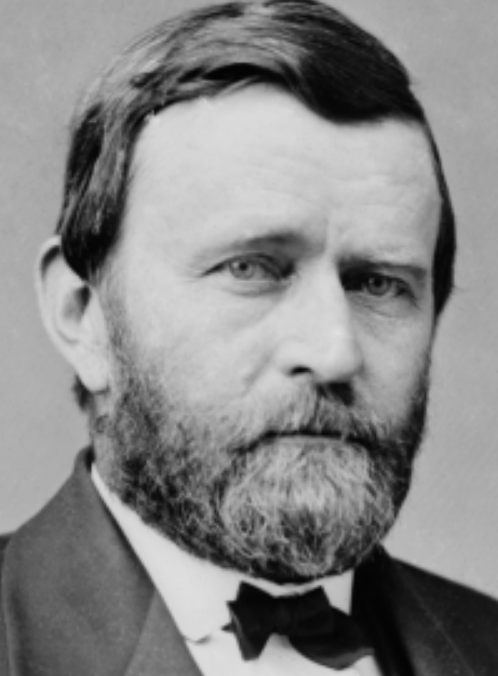

Ulysses S. Grant

On this date in 1822, Ulysses S. Grant, né Hiram Ulysses Grant, 18th U.S. president, was born in Point Pleasant, Ohio. The Union victory at the end of the Civil War was credited to Grant, who became General of the Army. Grant was U.S. president from 1869 to 1877.

He was a favorite of irreverent author Mark Twain, who gave the keynote at a toast for Grant at the Palmer House in Chicago in 1879 as part of an illustrious lineup of speakers that included agnostic Robert G. Ingersoll. Twain was entrusted to publish Grant’s Memoirs. He was not a member of any church and was never baptized.

After receiving eight demerits as a cadet at West Point for failure to attend chapel, he protested in a letter that it was “not republican” to be forced to go to church. (Brown’s Life of Grant, cited by Franklin Steiner in The Religious Beliefs of Our Presidents.)

Grant was on record in favor of taxation of church property. In an annual address to Congress in 1875, he warned of “the importance of correcting an evil that if permitted to continue, will probably lead to great trouble in our land. … It is the acquisition of vast amounts of untaxed Church property. … I would suggest the taxation of all property equally.” (D. 1885)

PHOTO: Grant c. 1870; Mathew Brady photo.

“Leave the matter of religion to the family altar, the Church, and the private schools, supported entirely by private contributions. Keep the church and state forever separate.”

— Grant address delivered in Des Moines, Iowa, in 1875

John F. Kennedy (Quote)

“I believe in an America where the separation of church and state is absolute — where no Catholic prelate would tell the president (should he be Catholic) how to act, and no Protestant minister would tell his parishioners for whom to vote — where no church or church school is granted any public funds or political preference — and where no man is denied public office merely because his religion differs from the president who might appoint him or the people who might elect him.

“I believe in an America that is officially neither Catholic, Protestant nor Jewish — where no public official either requests or accepts instructions on public policy from the pope, the National Council of Churches or any other ecclesiastical source — where no religious body seeks to impose its will directly or indirectly upon the general populace or the public acts of its officials — and where religious liberty is so indivisible that an act against one church is treated as an act against all.

“Finally, I believe in an America where religious intolerance will someday end — where all men and all churches are treated as equal — where every man has the same right to attend or not attend the church of his choice — where there is no Catholic vote, no anti-Catholic vote, no bloc voting of any kind — and where Catholics, Protestants and Jews, at both the lay and pastoral level, will refrain from those attitudes of disdain and division which have so often marred their works in the past, and promote instead the American ideal of brotherhood.”

— John F. Kennedy, born on May 29, 1917, died Nov. 22, 1963. Speech as a presidential candidate to the Greater Houston Ministerial Association, Rice Hotel, Sept. 12, 1960.

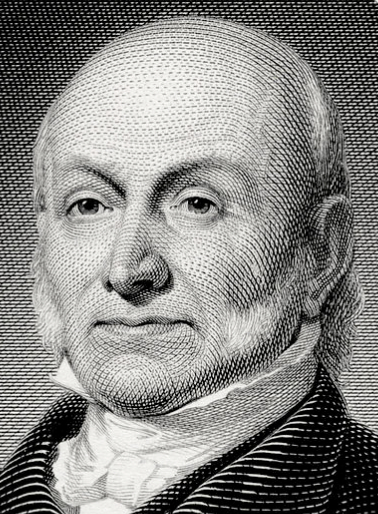

John Quincy Adams

On this date in 1767, John Quincy Adams was born in Massachusetts. He witnessed the Battle of Bunker Hill from above his family’s farm and accompanied his father John Adams (U.S. president 1797-1801) on a mission to France at age 12. Adams studied in France and later at the University of Leyden in Holland. He graduated from Harvard at 26 and began a career as lawyer, professor, writer and diplomat.

He was elected to the Massachusetts Senate in 1802 and became a U.S. senator in 1803. He spent several years as minister to Russia under President James Madison. He was one of the negotiators of peace with England in 1814, then served as minister to England until President James Monroe appointed him secretary of state.

Adams authored the Monroe Doctrine and helped negotiate acquisition of important territories. During his candidacy for president, no candidate — Andrew Jackson, Adams, W.H. Crawford or Henry Clay — received a majority of votes. Although Adams was in second place, the House of Representatives with Clay’s support elected Adams president. As president, he proposed a network of highways, the financing of scientific experiments and the building of an observatory.

He was defeated in 1828 but returned to Congress in 1830 and held his seat until his death in 1848. His distinguished career there, earning him the sobriquet of “Old Man Eloquent,” included his advocacy for the right of petition of abolitionist societies. He battled for eight years and finally succeeded in ending a Southern-imposed gag rule automatically tabling petitions against slavery.

Like his father, he was a Unitarian. He was critical of Sabbatarians and preachers who “rave and rant and talk nonsense for an hour” during sermons. (Diary entry, The Religious Beliefs of our Presidents.) Adams collapsed from a stroke on the floor of the U.S. House at age 80 and died two days later. (D. 1848)

“This young fellow, who was possessed of most violent passions, which he with great difficulty can command, and of unbounded ambition, which he conceals perhaps, even to himself, has been seduced into that bigoted, illiberal system of religion, which, by professing vainly to follow purely the dictates of the Testament, in vain contradicts the whole doctrine of the New Testament, and destroys all the boundaries between good and evil, between right and wrong.”

— J.Q. Adams, diary entry, "Life in a New England Town," 1787-88, cited by Franklin Steiner in "The Religious Beliefs of Our Presidents" (1936)

Michelle Bachelet

On this date in 1951, Michelle Bachelet was born in Santiago, Chile, to an archaeologist mother and father who was a general in the air force. She attended the University of Chile for an education in medicine, and during Salvadore Allende’s government, she participated in the Socialist Youth movement. General Pinochet, supported by the U.S. Central Intelligence Agency, led a coup in 1973 against the democratically elected Allende government, for which Bachelet’s father worked.

Bachelet watched the bombing of La Moneda Palace from the roof of her medical campus and later that day learned that her father had been arrested for treason. He died in prison a year later as a result of torture. She began hiding people wanted by Augusto Pinochet’s right-wing regime. In 1975 Pinochet’s secret police arrested Bachelet and her mother and exiled them to Australia after harsh interrogations. Eventually moving to East Germany, Bachelet attended medical school in Berlin and married an architect and fellow Chilean exile. They had two children together.

Bachelet returned to Chile in 1979 with her family and worked as a physician while becoming politically active when democracy was restored in 1990. In 2002 she was named to head the Defense Ministry, making her the first woman in Latin America to hold such a position. She served presidential terms from 2006-10 and from 2014-18, the first woman in Chile to occupy the position. In August 2018 the United Nations nominated her to become the next High Commissioner for Human Rights.

Bachelet endured much criticism for her open agnosticism and secular reforms such as making the morning-after pill free at state-run hospitals, an act which infuriated the Catholic Church. As reported in the Washington Post, Bachelet said, “I’m agnostic. … I believe in the state.” (“Female, Agnostic and the Next Presidente?” Dec. 10, 2005.)

Photo by Comando Michelle Bachelet at Descarga y Actua under Attribution-ShareAlike 3.0 Chile.

“I was a woman, a divorcee, a socialist, an agnostic … all possible sins together.”

— Bachelet, on why she was an unlikely contender for president of a strongly Catholic country, USA Today (Jan. 15, 2009)

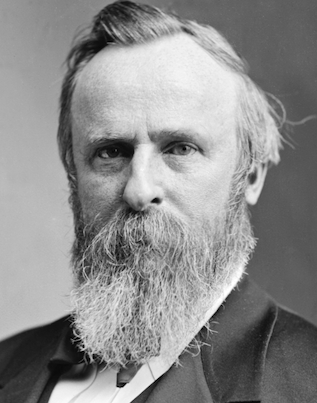

Rutherford B. Hayes (Quote)

“We all agree that neither the Government nor political parties ought to interfere with religious sects. It is equally true that religious sects ought not to interfere with the Government or with political parties. We believe that the cause of good government and the cause of religion both suffer by all such interference.”

— Rutherford B. Hayes, born Oct. 4, 1822 (D. 1893); speech in Marion, Ohio, July 31, 1875, two years before he was elected U.S. president. Hayes, who previously served as an Ohio congressman and governor, spoke out against Catholic intrusion into public education while campaigning for governor. That led to some branding him as anti-Catholic, when in reality he opposed all sectarian interference with public schools, even though he attended church regularly.

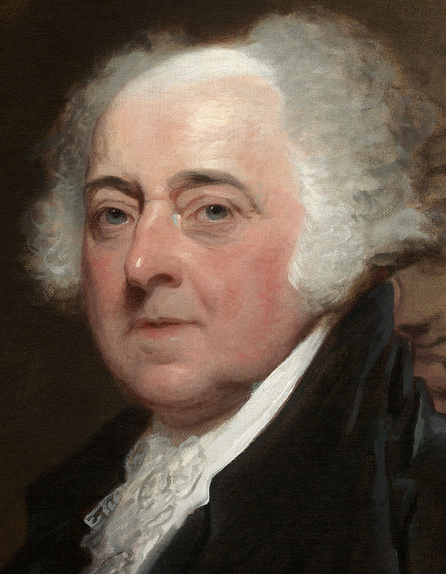

John Adams

On this date in 1735, John Adams, who became the second U.S. president, was born to John Adams Sr. and Susanna Boylston Adams on a farm in Braintree (now Quincy), Mass. Harvard-educated, he chucked ministerial studies for the law. In his Works, he wrote, “People are not disposed to inquire for piety, integrity, good sense or learning in a young preacher, but for stupidity (for so I must call the pretended sanctity of some absolute dunces), irresistible grace, and original sin.” He married Abigail Smith, who later fruitlessly urged him to “remember the ladies” in the Constitution. Their son, John Quincy Adams, became the sixth U.S. president.

A revolutionary, John Adams opposed the Stamp Act, was a delegate at the First and Second Continental Congresses and proposed George Washington as commander of the military. Adams seconded the motion for the Declaration of Independence. He was also a diplomat. Adams carefully studied religion. According to the biography by his somewhat orthodox grandson, he was “very much in the mold accepted by the Unitarians of New England,” while other historians put him squarely in the deist camp. Later in life he joined the Unitarian Church.

Adams wrote Thomas Jefferson: “Twenty times in the course of my late readings, I have been on the point of breaking out, ‘This would be the best of all worlds if there were no religion in it!’ ” But Adams qualified that by adding, “Without religion, this world would be something not fit to be mentioned in polite company — I mean hell.”

Adams didn’t believe in miracles or prophecies, eternal damnation or demonic possession and wrote a History of the Jesuits as an exposé. In the Massachusetts constitutional conventions of 1779 and 1820, he fought to separate church and state, a reform adopted after his death.

“Although both Jefferson and Adams denied the miracles of the Bible and the divinity of Christ, Adams always retained a respect for the religiosity of people that Jefferson never had; in fact, Jefferson tended in private company to mock religious feelings.” (Friends Divided: John Adams and Thomas Jefferson by Gordon S. Wood, 2017)

Adams believed in an afterlife for emotional reasons. “If I did not believe in a future state, I should believe in no God,” he wrote Jefferson. Adams wrote a three-volume treatise on the U.S. Constitution. He was vice president under Washington from 1788-96 and was elected president in 1796, serving one term. Although he and Jefferson both died on the 50th anniversary of the July 4 adoption of the Declaration of Independence, Adams’ dramatic dying words were “Jefferson lives.” (D. 1826)

“Can a free government possibly exist with the Roman Catholic religion?”

— Letter to Jefferson dated May 19, 1821, in which Adams called free government "a complicated piece of machinery."