May 6

George Clooney

On this date in 1961, Oscar-winning actor George Clooney was born in Lexington, Ky. Clooney, whose aunt was the famous singer Rosemary Clooney, attended Northern Kentucky University. Clooney’s acting career began on television in the early 1980s, where he played in such shows as “Roseanne.” He was a regular on “ER” from 1994-99. Clooney has made numerous movies, including a comic turn as a skeptical, Depression-era Ulysses in “O Brother, Where Art Thou” (2000).

Other notable movies include “Three Kings” (1999), “The Perfect Storm” (2000), “Ocean’s Eleven” (2001, plus two sequels), “Gravity” (2013), “Tomorrowland” (2015) and “Hail, Caesar!” in 2016. Clooney has directed films, including “Good Night, and Good Luck” (2005), and has worked with Stephen Soderbergh, the freethinking director.

Clooney won the 2006 Academy Award for Best Supporting Actor for his role in “Syriana” (2005), received a 2012 Oscar for co-producing “Argo” and was the recipient of the AFI Lifetime Achievement Award in 2018. His Oscar nominations include Best Actor for “Up in the Air” (2009), Best Actor for “Michael Clayton” (2007), and both Best Director and Best Original Screenplay for “Good Night, and Good Luck.” He won Golden Globes for “Syriana,” “O Brother, Where Art Thou?” and “The Descendants” (2011).

His charitable work includes service as a “United Nations Messenger of Peace” since 2008, his advocacy regarding the Darfur conflict and his organization of the “Hope for Haiti” telethon to raise money for the victims of the 2010 earthquake.

PHOTO: Clooney in 2016; White House photo by Pete Souza.

“I don’t believe in heaven and hell. I don’t know if I believe in God. All I know is that as an individual, I won’t allow this life — the only thing I know to exist — to be wasted.”

— Clooney profile in the Washington Post (Sept. 28, 1997)

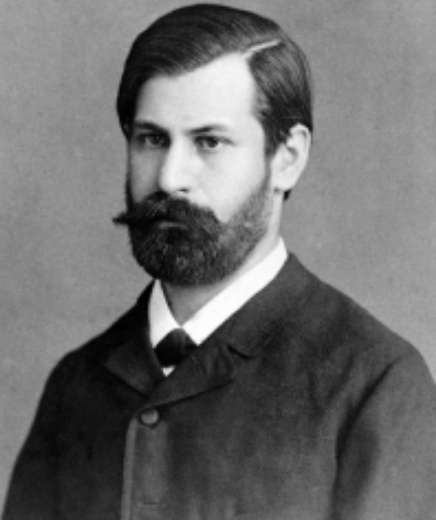

Sigmund Freud

On this date in 1856, Sigmund Freud was born in Moravia. He grew up in Vienna, where he lived until fleeing the Nazis in 1938. He earned a medical degree from the University of Vienna in 1881. He and Joseph Breuer co-wrote Studies in Hysteria (1895). Freud developed his theory on psychoanalysis, then wrote The Interpretation of Dreams (1900), The Psychopathology of Everyday Life (1904), Jokes and Their Relation to the Unconscious (1905), Three Essays on Sexual Theory (1905), Beyond the Pleasure Principle (1920) and The Ego and the Id (1923).

The Future of an Illusion (1927) is his masterpiece critique of religion, postulating that God is a projection of childish father-figure preoccupations, that prayer and religious ritual are obsessive-compulsive and that religion is a “universal neurosis.”

Freud followed that with Moses and Monotheism (1938), in which he wrote: “[Religion’s] doctrines carry with them the stamp of the times in which they originated, the ignorant childhood days of the human race. Its consolations deserve no trust.” Civilization and its Discontents (1929) also addressed Freud’s views on religion. In The Future of an Illusion he wrote that “in the long run, nothing can withstand reason and experience, and the contradiction which religion offers to both is all too palpable.”

In 1933 he collaborated with Albert Einstein on Why War?, a compilation of their memorable correspondence. Dying of mouth cancer after more than 30 operations, Freud ended his suffering with physician-prescribed morphine. (D. 1939)

“Religion is comparable to a childhood neurosis.”— Freud, "The Future of an Illusion" (1927)

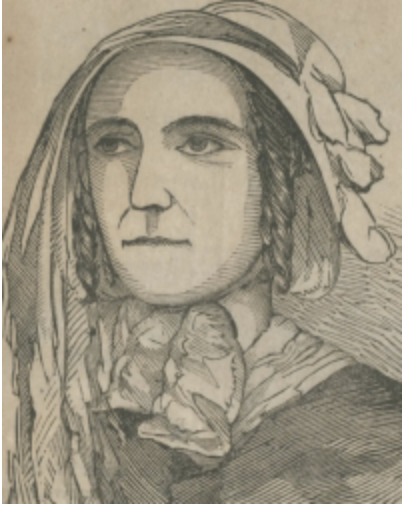

Margaret Cole

On this date in 1893, English socialist, politician and poet Margaret Isabel Cole (née Postgate) was born in Cambridge, England, to John and Edith (Allen) Postgate. They raised her with a well-rounded education at Roedean School and Girton College, Cambridge. During her time at Girton, Cole was inspired by the works of intellectuals such as J.A. Hobson, H.G. Wells, Sidney Webb, Beatrice Webb, George Bernard Shaw and Noel Brailsford.

These readings led her toward a life of socialism, feminism and atheism and away from her conventional Anglican upbringing. Cole became a classics teacher at St. Paul Girls School at Cambridge. Her brother shared some of her interests and was imprisoned during World War I as a conscientious objector.

While working with the No-Conscription Fellowship, she met George Cole, who led a movement known as Guild Socialism. They married in 1918 and joined the socialist Fabian Society before moving to Oxford in 1924. During their time there they taught, co-authored numerous mystery novels and created the Socialist League. Although she was anti-World War I, she espoused military action in the 1930s after witnessing the rise of Hitler and the Nazi Party.

In 1949, her autobiography, Growing Up Into Revolution, was published. She wrote many other books, including a biography of her husband.

Cole was committed to the well-being of London’s citizens and came to be a founding member of the Inner London Education Authority in 1965, where she remained until 1967, when she retired. She received the Order of the British Empire in 1965, the equivalent of being knighted for men, and thus became Dame Margaret Cole. She used her academic exposure to introduce comprehensive education in London throughout the rest of her life. (D. 1980)

PHOTO: Reproduction of a Cole portrait by Australian artist and feminist Stella Bowen, c. 1944.

“[Conscientious objection] on religious grounds was for most part treated with respect, particularly if the sect had a respectable parentage. … But non-Christians who objected on the grounds that they were internationalists or Socialists were obvious traitors in addition to all their other vices, and could expect little mercy.”

— Margaret Cole, "Growing Up Into Revolution" (1949)

Madame Restell

On this date in 1811, Madame Restell (né Ann Trow) — feminist, midwife and abortion provider — was born in Painswick, Gloucestershire, England, the only daughter of Anne (Biddle) and John Trow. She had seven brothers. Their father was an agricultural laborer.

Hers is a rags-to-riches story that ended tragically. She started working as a maid at age 15 and married Henry Summers, a tailor, in 1829. In 1831, after their daughter Caroline was born, they emigrated to New York, where Summers, an alcoholic, died of typhoid a few months later.

She supported herself and Caroline as a seamstress before marrying Charles Lohman, a printer at the New York Herald, in 1833. He was well-educated and frequented a bookstore where philosophers and freethinkers gathered to debate, and he started publishing tracts about birth control.

In partnership with her husband and brother, she started selling patent medicines and herbal contraceptive products advertised under the name Madame Restell. She sold through the mail and made home visits if the abortifacient failed to end a pregnancy. As a self-professed “female physician” and “professor of midwifery,” she built a thriving practice.

“Madame Restell lived in a period where abortion went from being a common misdemeanor in the first few months of pregnancy to literally unspeakable after the Comstock laws in 1873 banned information regarding abortion and birth control,” said biographer Jennifer Wright. “It’s estimated that around 1 in 5 pregnancies during the mid-19-century ended in abortion.” Wright called Comstock “a chronic masturbator.” (Wright interview, Feminist Book Club, Feb. 13, 2023)

Imprisoned for a year at mid-century for performing an abortion, Restell received special treatment from the warden, whose wife prepared her meals. She was allowed to wear her own clothes and have other privileges. After her release, Restell said she would no longer offer surgical abortions but would still provide pills and stays in her boardinghouse, where women with unwanted pregnancies could give birth in anonymity. For an additional fee, she facilitated the adoption of infants. She was granted U.S. citizenship in 1854.

“Lifting passages from the social reformer Robert Dale Owen, she likened abortion and contraception to a lightning rod — an invention that was ‘unnatural,’ perhaps, but sensible and lifesaving. … Pious orphanages did not accept ‘foundlings,’ the product of a live woman’s sin, so many were left in almshouses, where 90 percent would die. A strong cultural belief in hereditary criminality made adoption rare.” (New York Times, Feb. 28, 2023)

She and her husband amassed a considerable amount of money through the years and lived in a capacious Manhattan brownstone at 52nd Street and 5th Avenue. It was built there in 1862, the story goes, to aggravate Catholic Archbishop John Joseph Hughes, who had purchased the adjoining block to rebuild St. Patrick’s Cathedral. The next block over housed the Catholic Orphan Asylum. Hughes denounced Restell from the pulpit for “crimes against God.”

Congress enacted the Comstock laws in 1873. Comstock at times would personally hunt down alleged violators, and in 1878 he surreptitiously bought some pills from Restall, claiming to be a married man whose wife had already given him too many children. He returned the next day with a police officer who arrested her.

There would be no trial, because on April 1, 1878, a maid discovered Restell naked in the bathtub with her throat slit. “A coroner’s jury … viewed the body, and gave a verdict of suicide. The next day the corpse, in a coffin of rosewood, was taken by train to Tarrytown and buried in the plot in Sleepy Hollow Cemetery where Madam Restell’s second husband lay. There was no religious ceremony, and Madam’s surviving daughter was not there.” (The New Yorker, Nov. 15, 1941)

Not everyone was convinced at the time it was suicide. Nor does author Sharon DeBartolo Carmack, who in her 2023 book “Madame Restell: The True Story of New York City’s Most Notorious Abortionist. Her Early Life, Family, and Murder,” presents an argument for “a far more tragic end” to Restell’s life, which ended at age 65. (D. 1878)

“Members of the American Female Moral Reform Society attempted to give her religious tracts when she was in prison, which she rejected, claiming she had enough novels.”

— Jennifer Wright interview, Feminist Book Club (Feb. 13, 2023)