March 28

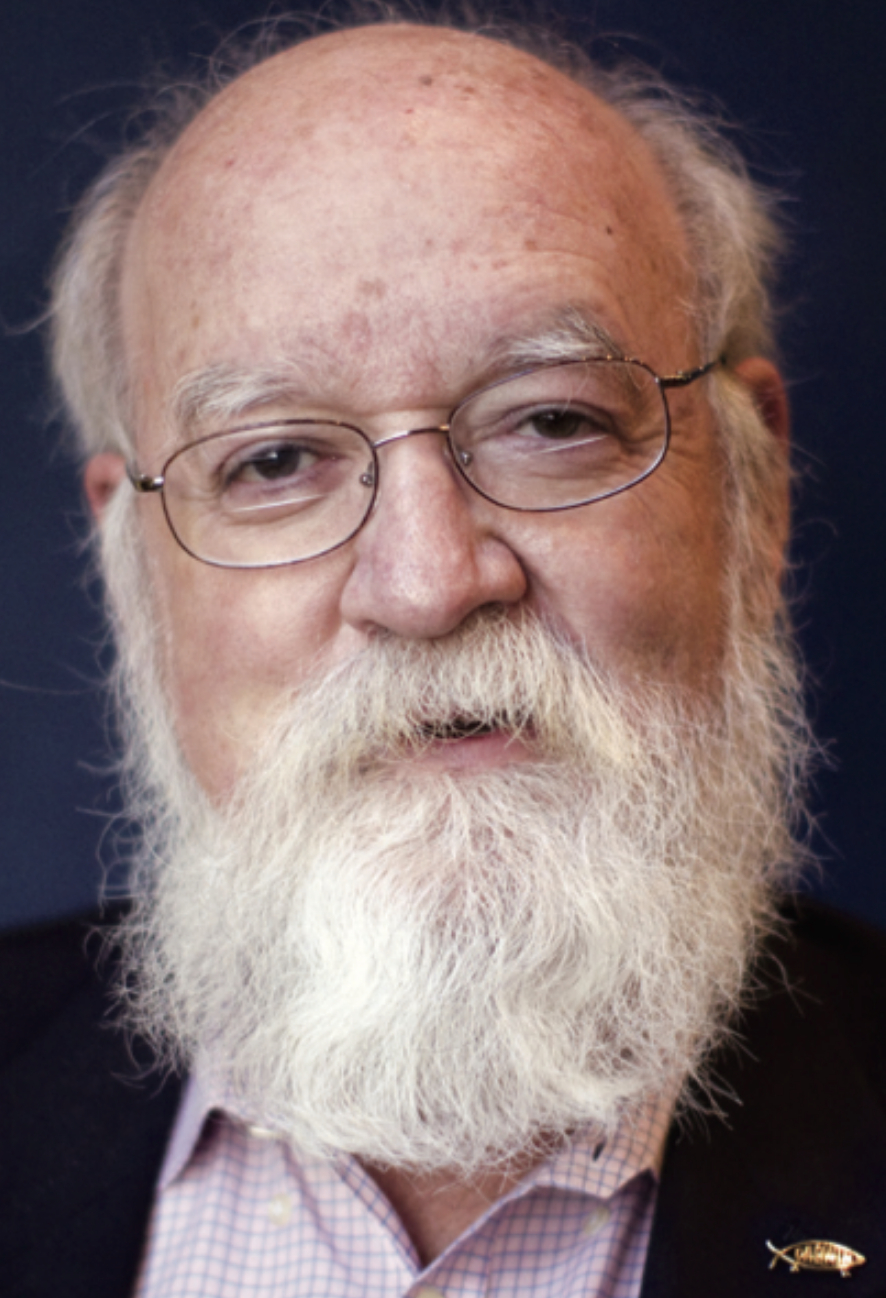

Daniel C. Dennett

On this date in 1942, philosopher Daniel Clement Dennett III was born in Boston, the son of Ruth Marjorie (née Leck) and Daniel Clement Dennett Jr. He earned his B.A. in philosophy at Harvard in 1963 and his doctorate in philosophy from Oxford in 1965. Since 1971, he taught at Tufts University with the exception of visiting professorships and was Austin B. Fletcher Professor of Philosophy there. His specialty was consciousness.

His 1992 book Consciousness Explained was widely credited with advancing the understanding of how various parallel brain processes contribute to consciousness. He also wrote often about the philosophy of the mind and of science and was considered a leading proponent of “neural Darwinism.”

Among his many books are Darwin’s Dangerous Idea (1995), Freedom Evolves (2003), Breaking the Spell: Religion as a Natural Phenomenon (2006), Kinds of Minds: Towards an Understanding of Consciousness (1997), Science and Religion (2010), Caught in the Pulpit: Leaving Belief Behind (with Linda LaScola, 2013) and From Bacteria to Bach and Back: The Evolution of Minds (2017).

His well-known 2003 New York Times piece endorsing the use of the term “Bright” to describe the nonreligious began: “The time has come for us brights to come out of the closet. What is a bright? A bright is a person with a naturalist as opposed to a supernaturalist world view. We brights don’t believe in ghosts or elves or the Easter Bunny — or God. We disagree about many things, and hold a variety of views about morality, politics and the meaning of life, but we share a disbelief in black magic — and life after death.”

His scholarship earned Dennett a place among the “Four Horsemen” of literary atheism, along with Richard Dawkins, Sam Harris and the late Christopher Hitchens. Dennett received FFRF’s Emperor Has No Clothes Award in 2008 and in his acceptance speech urged atheists to “come out of the closet.” He was a co-founder of the Clergy Project in 2011 and was an FFRF honorary officer.

He and Susan Bell married in 1962 and lived in North Andover, Mass. They had a son, Peter, and a daughter, Andrea. He died at age 82 at the Maine Medical Center in Portland of complications from interstitial lung disease. (D. 2024)

“Politicians don’t think they even have to pay us lip service, and leaders who wouldn’t be caught dead making religious or ethnic slurs don’t hesitate to disparage the ‘godless’ among us.”

“From the White House down, bright-bashing is seen as a low-risk vote-getter. And, of course, the assault isn’t only rhetorical: the Bush administration has advocated changes in government rules and policies to increase the role of religious organizations in daily life, a serious subversion of the Constitution. It is time to halt this erosion and to take a stand: the United States is not a religious state, it is a secular state that tolerates all religions and — yes — all manner of nonreligious ethical beliefs as well.”

— Dennett, "The Bright Stuff," New York Times (July 12, 2003); photo by Brent Nicastro

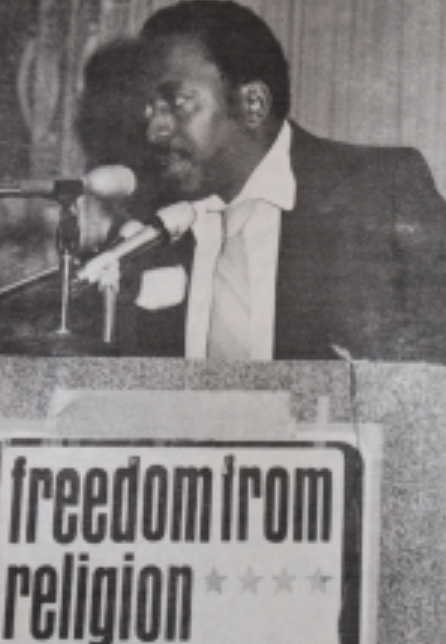

Ishmael Jaffree

On this date in 1944, Ishmael Jaffree (né Frederick Hobbs) was born two months prematurely in a Cleveland home for unwed mothers. His mother was very religious and he never knew his father. Jaffree brought and won the U.S. Supreme Court decision Wallace v. Jaffree, 472 U.S. 38, 72 (1985). Calling him “an authentic American hero,” FFRF inaugurated its Freethinker of the Year award at its 1985 convention to recognize his contributions.

As a child he evangelized on Cleveland street corners, “exhorting sinners to get right with God,” according to a People magazine story (June 24, 1985). At Cleveland State University, he was influenced by a black atheist professor named Jaffree. “I started considering myself an Existentialist. I no longer believed the Christian faith was the faith and that Jesus Christ had blue eyes and white skin.” He changed his name in 1972 to reject “the slave-master path. Ishmael means outcast.”

He married Mozelle Hurst in 1974 after finishing law school. They moved to Alabama in 1977, where he set up a law practice in Mobile. He discovered in 1981 that his children were being fed daily doses of the Lord’s Prayer and grace at lunch, with an occasional bible reading. Jaffree bravely filed a lawsuit in May 1982, challenging a 1978 law authorizing a one-minute period of silence, a 1981 statute authorizing a period of silence “for meditation or voluntary prayer,” and a 1982 law authorizing teachers to lead “willing students” in a prescribed prayer to “Almighty God … the Creator and Supreme Judge of the world.”

During the 1982 trial, U.S. District Judge William Brevard Hand allowed 600 Christians to intervene; school officials led children in prayer in front of media. Jaffree’s children were ostracized, laughed at and subjected to racial epithets and physical harassment. Hand ruled against Jaffree in 1983, claiming the Supreme Court was wrong about state-church separation and that the First Amendment does not bar states from establishing a religion. The case proceeded by way of the 11th Circuit U.S. Court of Appeals to the U.S. Supreme Court.

On June 4, 1985, the Supreme Court ruled 6-3 in Jaffree’s favor, declaring unconstitutional a period of silence for “meditation or voluntary prayer” in public schools.

{Hand received more national attention two years later when he ruled for plaintiffs who claimed Alabama textbooks promoted secular humanism and violated the Establishment Clause. Hand, appointed as a federal judge by President Nixon, ordered statewide removal of textbooks in home economics, history and social studies. The 11th Circuit later overruled him unanimously.)

“I brought the case because I wanted to encourage toleration among my children. I certainly did not want teachers who have control over my children for at least eight hours over the day to … program them into any religious philosophy.”

— Jaffree, acceptance speech as FFRF's first Freethinker of the Year (1985)

Jane Rule

On this date in 1931, lesbian writer Jane Rule was born in Plainfield, New Jersey. She graduated from Mills College, Oakland, California, in 1952 and became an occasional student at University College, London. Her first book, Desert of the Heart, a novel, was turned into the 1984 movie, “Desert Heart.” While teaching at Concord Academy in Massachusetts, she fell in love with Helen Sonthoff, a creative writing instructor who was married to Herbert Sonthoff, a German who had fled the Nazi regime.

Rule moved to Vancouver, British Columbia, in 1956 and taught intermittently at the University of British Columbia until 1976. At age 40, Sonthoff came to Vancouver to visit Rule, then 25, and they resumed their intimate relationship. They lived as a couple until Sonthoff died in 2000.

She was good friends with writers Kate Millett and Margaret Atwood. Among her many books, which include novels and nonfiction, are After the Fire (1988), Memory Board (1987), Hot-Eyed Moderate (1985), Contract with the World (1982) and Lesbian Images (1982). Among her awards were being named author of the Best Story of the Year 1978 by the Canadian Authors Association. She died of liver cancer in 2007.

“I’m a nonbeliever. I don’t believe in the existence of a God. I don’t believe in the Christian dogma. I find it horrifyingly silly. The intolerance that flows from organized religion is the most dangerous thing on the planet.”

— Rule, "Brave Souls: Writers and Artists Wrestle with God, Love, Death and the Things That Matter" by Douglas Todd (1996)

Neil Kinnock

On this date in 1942, British Labour Party leader Neil Kinnock was born in Tredegar, Wales. His father was a miner and his mother a nurse. Neil attended the University College, Cardiff, where he met his wife, Glenys, who became a Labour MP. Kinnock was elected to Parliament with the Labour Party at age 28 and became party leader by 1983. He resigned in 1992 after his party’s national defeat.

In 1995 he became the European Union’s European Commissioner, then vice president (1999-2004). In 2005 he was introduced into the House of Lords as Baron Kinnock of Bedwelty, which he accepted “for practical political reasons.”

He has been described as an agnostic and an atheist. He and his wife are both patrons of Humanists UK, a charitable group that aims to represent “people who seek to live good lives without religious or superstitious beliefs.”

“When Neil Kinnock spoke about his atheism, he was monstered, as if this were evidence of his otherness. In fact, he was at the vanguard of a growing secularist trend.”

— "Faithless Britain is still a country of compassion and principles," The Telegraph (Oct. 4, 2012)

Corliss Lamont

On this date in 1902, Corliss Lamont was born in Englewood, N.J. His father, Thomas W. Lamont, was a chairman of J.P. Morgan & Co. He attended Phillips Exeter Academy and received his bachelor’s degree from Harvard University in 1924. He went on to obtain his Ph.D. in philosophy from Columbia University in 1932. Lamont supported many radical causes, including socialism, and although he never joined the Communist Party, he was strongly opposed to the persecution of communists.

He served as the director of the the American Civil Liberties Union from 1932 until 1954. He was a founder in 1954 of the National Emergency Civil Liberties Committee. After being called before the House Un-American Activities Committee because of a book he had written, The Peoples of the Soviet Union (1946), he was cited for contempt of Congress. The indictment was dismissed by the Court of Appeals on the grounds that he was outside the jurisdiction of the committee.

Lamont wrote many books, pamphlets and essays, including many on humanism. His influential book The Philosophy of Humanism (1949), was based on a course he taught at Columbia in the 1940s and 1950s on naturalistic humanism. Other books on humanist subjects include his classic The Illusion of Immortality (1935), which argued against the imortality of the soul. He also wrote A Humanist Funeral Service (1954) and A Humanist Wedding Service (1970).

He was an active member for many years of the American Humanist Association and in 1977 received its Humanist of the Year award. He died of heart failure at age 93 in 1995.

“The greatest difference between the Humanist ethic and that of Christianity and the traditional religions is that it is entirely based on happiness in this one and only life and not concerned with a realm of supernatural immortality and the glory of God. Humanism denies the philosophical and psychological dualism of soul and body and contends that a human being is a oneness of mind, personality, and physical organism. Christian insistence on the resurrection of the body and personal immortality has often cut the nerve of effective action here and now, and has led to the neglect of present human welfare and happiness.”

— Lamont, “The Affirmative Ethics of Humanism,” The Humanist (March/April 1980)