dancers

Mikhail Baryshnikov

On this date in 1948, Mikhail Nikolaevitch Baryshnikov was born in Riga, Latvia. His father was an engineer and his mother was a seamstress who introduced him to ballet when he was 9. A strong athlete, Baryshnikov played sports in school but turned completely toward ballet when he was 12 after his mother committed suicide. At 15 he began studying with the Kirov Ballet, where he stayed for the next five years under the direction of Alexander Pushkin.

He became Kirov’s principal dancer at age 21 and began earning recognition for his strong technique and gravity-defying leaps. While on tour in Canada at age 26, he defected to America. Granted political asylum, Baryshnikov began working as principal dancer with the American Ballet Theatre (ABT) in New York, where he stayed for five years before joining the New York City Ballet. Working under George Balanchine and Jerome Robbins, he expanded his repertoire, as well as the role of male dancers in ballet. He then returned to ABT as principal dancer as well as artistic director, a position he held for 10 years.

In 1990 he teamed with choreographer Mark Morris to found the White Oak Dance Project and, in 2005, opened the Baryshnikov Arts Center in New York. Observing that the challenge of dancing different choregraphies and styles is similar to learning a new language, Baryshnikov wrote in his 1976 autobiography, “Every ballet, whether or not successful artistically or with the public, has given me something important. Everything that I’ve done has given me more freedom.” (Baryshnikov at Work).

He has appeared in the films “Turning Point” (1977) and “White Nights” (1985), on Broadway (“Metamorphosis”) and on television, in a regular role on HBO’s “Sex and the City.” Baryshnikov has been awarded the Kennedy Center Honors Lifetime Achievement Award (2000), Outer Critics Circle Award for Best Actor in a Play (1989), an Emmy for Outstanding Variety or Music Program (1979-80), an Emmy for Outstanding Individual Achievement-Special Events (1978-79) and an Oscar for Best Supporting Actor (1977).

Baryshnikov has four children, the oldest with actress Jessica Lange and the three youngest with ballerina Lisa Rinehart. They married in 2006 and live in New York as of this writing.

PHOTO: Baryshnikov in 2017; photo under CC 2.0.

“I don’t believe in marriage in the conventional way. I am not [a] religious person, and marriage in front of [the] altar wouldn’t say anything to me.”

— interview, CNN "Larry King Weekend" (May 5, 2002)

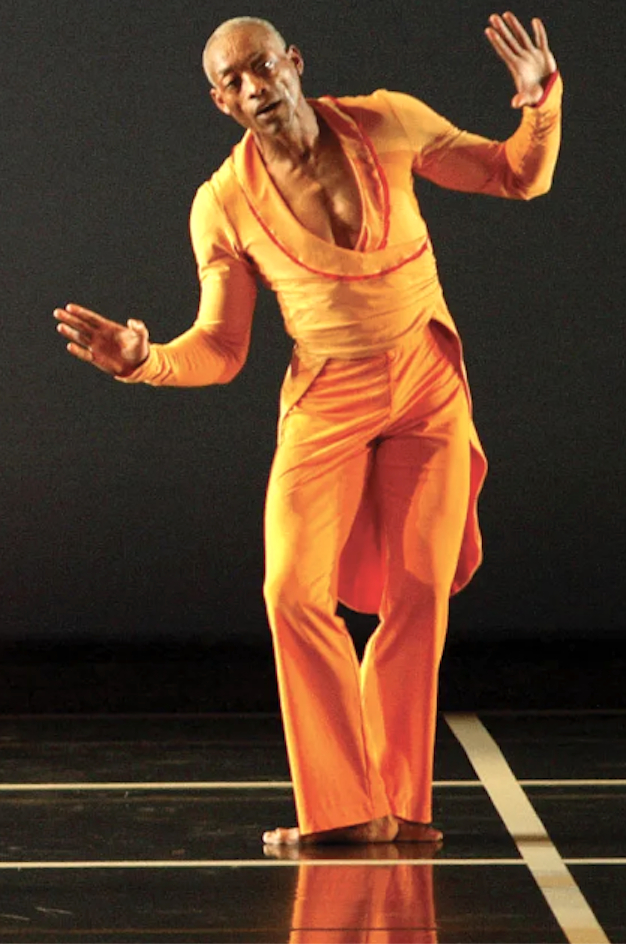

Bill T. Jones

On this date in 1952, William Tass “Bill T.” Jones was born in Bunnell, Fla., the 10th of 12 children born to Estella (Edwards) and Augustus Jones, migrant farm workers. The family followed the crops north and settled when he was 3 in Wayland, N.Y. “I am a child of potato pickers who wept at the Civil Rights Act of 1964, because they knew what it meant,” Jones later said. “They knew what had been denied them before.” (The Guardian, June 11, 2004)

He starred in track in high school and participated in drama and debate. After graduation he enrolled at the State University of New York at Binghamton, where he studied classical ballet and modern dance and took classes in west African and African-Caribbean dancing. Binghamton was where he fell in love with Arnie Zane. Their personal and professional relationship lasted until Zane’s death from AIDS in 1988.

With Lois Welk and Jill Becker, they formed American Dance Asylum in 1974 and began emphasizing a partnering technique called contact improvisation. Jones created a number of solo pieces during this period and performed in New York City. Interested in living in an area more supportive of the arts and of an interracial gay couple, he and Zane moved in 1979 to Rockland County just outside the Bronx.

Their duets featured photography, singing, and spoken dialogue with a political and social focus and acknowledgement of their personal relationship. A trilogy they created in 1979-81 — “Blauvelt Mountain,” “Monkey Run Road” and “Valley Cottage” — broke choreographic ground.

They formed the Bill T. Jones/Arnie Zane Dance Company in 1982, recruiting nontraditional performers representing different body sizes, shapes and colors. “Jones, a choreographic provocateur, presents his ideas about identity, art, race, sexuality, nudity, power, censorship, homophobia and AIDS-as-chemical-warfare with a streetwise, in-your-face attitude,” said a 1998 entry in the “International Encyclopedia of Dance.”

“Last Supper at Uncle Tom’s Cabin/The Promised Land” (1990) explored differences not only in body shapes but attitudes, race and sexuality. It was also about Jones’ conflict with faith, despite growing up in a devoutly Christian home. He has called it “a dialogue with my mother’s faith.” (Which never included 52 nude bodies dancing à la the piece’s fifth and final section.) “Last Supper” questioned how God could allow the cruelties of slavery and AIDS to happen. Zane had died in 1988 at age 39 of AIDS-related lymphoma. Jones’ piece “Absence” evoked his memory.

In an interview with Jeffrey Brown (Oct. 8, 2021) for “News Hour” on PBS, he told Brown “I’m an atheist.”

“Still/Here” (1995), a major midcareer work, was controversial in some quarters. It was “a meditation about mortality in which Jones incorporated the movements of terminally ill people whom he’d met in the free dance workshops he’d set up for them, the patients becoming, in a sense, collaborators.” (New York Times, June 6, 2016) New Yorker dance critic Arlene Croce called it “victim art” and refused to see the production.

With over 120 works for his own company, Jones has also choreographed for Alvin Ailey American Dance Theater and numerous other companies. “Arguably the most written-about figure in the dance world of the last quarter century, Jones is inarguably the most broadly laureled, with a National Medal of Arts and a Kennedy Center Honor and Tony Awards and a Dorothy & Lillian Gish Prize and a MacArthur Fellowship and, without hyperbole, scores more.” (Ibid.) His memoir “Last Night on Earth” was published in 1995.

Jones is married to designer and creative director Bjorn Amelan, a French national raised in Haifa, Israel, and several European countries. They have been together since 1993, when he started designing many of Jones’ sets.

“I am a humanist, as all Christians are supposed to be. For me, the bottom line is commonality. It is the only thing I accept. I don’t even know if a soul exists. But I do know there is a condition called humanity that we are a part of, with wonderful potential for good and evil. I believe in limited free will. God? I believe there is an intelligence in the universe, but I don’t believe in absolute morality, in sin.”

— Interview, Los Angeles Times (March 10, 1991)

Isadora Duncan

On this date in 1878, Isadora Duncan was born in San Francisco, the youngest of four children. Her mother, Dora Gray Duncan, a pianist and music teacher, was devout, having been raised in an Irish Catholic family. Dora lost her faith when her marriage disintegrated. Faced with four children to raise alone, “her faith in the Catholic religion revolted violently to definite atheism, and she became a follower of Robert Ingersoll, whose works she used to read to us,” Duncan recalled in her autobiography.

When she was 5, her teacher told the class that Santa Claus had provided candies and cakes as a special treat. When Duncan solemnly challenged the assertion, she was made to leave the class. She made a little speech (see quote below), which she called “the first of my famous speeches.” Her mother comforted her by saying, “There is no Santa Claus and there is no God, only your own spirit to help you.”

Duncan was dancing in public by age 6, encouraged by her mother to pursue her precocious talent. Considered the “mother of modern dance,” she pioneered interpretative dance, shedding shoes to dance barefoot, draping herself in loose Greek robes. She found fame and success in Europe and was the most famous dancer of her era.

Never conventional, Duncan gave birth to two “love children” by different fathers, neither of whom she married. Her children tragically drowned in 1913 in an accident in France. She died in Nice in another tragic accident, when her free-flowing scarf got caught in the spoked wheels of a French-made Amilcar convertible in which she was a passenger. (D. 1927)

PHOTO: Duncan c. 1906-12.

“I don’t believe lies!”

— Duncan, age 5, defying a teacher who insisted Santa Claus was real, "Isadora Duncan: My Life" (1927)