biologists

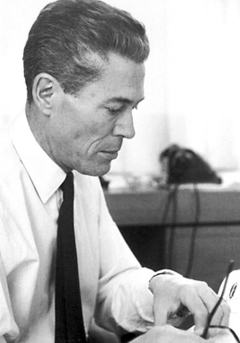

Jacques Monod

On this date in 1910, French biologist and Nobel Prize winner Jacques Lucien Monod was born in Paris to an American mother (Charlotte MacGregor Todd from Milwaukee) and a French Huguenot father, Lucien Monod, who was a painter and inspired him artistically and intellectually. In his doctoral work at the Sorbonne, Monod coined the term diauxie, meaning two growth phases, to describe different growth patterns he observed in bacteria. Monod is most famous for discovering, along with Francois Jacob and Andre Lwoff, the Lac operon feedback mechanism in living cells.

Monod received the 1963 Legion d’honneur, the highest decoration in France, for the operon theory of genetic control. The 1965 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine was awarded jointly to Monod, Jacob and Lwoff “for their discoveries concerning genetic control of enzyme and virus synthesis,” according to the Nobel Foundation website. Monod was among the first to suggest the existence of messenger RNA molecules. He’s considered one of the founders of molecular biology.

In addition to his scientific work, Monod was a talented musician and wrote on the philosophy of science. In his 1971 book, Chance and Necessity, he expounded on “an entirely non-providential view of the biological world as the mere product of chance and necessity, and proposed that the natural sciences reveal a purposeless world which entirely undercuts the tradition claims of religions.” (Cambridge University website, “Investigating Atheism.”)

In 1938 Monod married Odette Bruhl, an archaeologist and curator of the Guimet Museum in Paris. Their twin sons became a geologist and a physicist. He died of leukemia at age 66 and is buried in Cannes on the French Riviera. (D. 1976)

“As nontheists, we begin with humans not God, nature not deity.”

— Humanist Manifesto II (1973), of which Monod was one of the signatories when he was at the Institut Pasteur.

PZ Myers

On this day in 1957, biologist Paul Zachary “PZ” Myers was born. Myers is a biology professor at the University of Minnesota-Morris. His specialty is developmental biology and he is a proud proponent of science, evolution and atheism. He graduated from the University of Washington with a degree in zoology in 1979 and went on to earn his Ph.D in biology from the University of Oregon.

Before employment at UM-Morris, Myers worked at the University of Oregon, the University of Utah and Temple University. Myers studies zebrafish, spiders and cephalopods, an ink-squirting class of marine animals, most notably octopuses and squids.

“Pharyngula,” his very popular science blog, is partnered with National Geographic and has won numerous awards, including a 2005 Koufax Award for Best Expert Blog and an award from Nature. Myers was named Humanist of the Year in 2009 by the American Humanist Association, and won the International Humanist Award in 2011.

Myers makes his religious beliefs clear on Pharyngula: “If you’ve got a religious belief that withers in the face of observations of the natural world, you ought to rethink your beliefs — rethinking the world isn’t an option.” Commenting on his 2013 book The Happy Atheist, he said, “I’m an atheist swimming in a sea of superstition, surrounded by well-meaning, good people with whom I share a culture and similar concerns, and there’s only one thing I can do. I have to laugh.”

Myers at Ken Ham’s Creation Museum in Kentucky in 2009; syslfrog photo under CC 2.0.

"What I want to happen to religion in the future is this: I want it to be like bowling. It’s a hobby, something some people will enjoy, that has some virtues to it, that will have its own institutions and its traditions and its own television programming, and that families will enjoy together. It’s not something I want to ban or that should affect hiring and firing decisions, or that interferes with public policy. It will be perfectly harmless as long as we don’t elect our politicians on the basis of their bowling score, or go to war with people who play nine-pin instead of ten-pin, or use folklore about backspin to make decrees about how biology works."

— Myers, interviewed in the 2008 documentary "Expelled: No Intelligence Allowed"

Richard Dawkins

On this date in 1941, evolutionary biologist and freethought champion Clinton Richard Dawkins was born in Nairobi, Kenya. His father, Clinton John Dawkins, was an agricultural civil servant in the British Colonial Service and served with the King’s African Rifles in World War II. The family returned to England in 1949. Dawkins graduated from the University of Oxford in 1962, then earned a philosophy doctorate and became an assistant professor of zoology at the University of California-Berkeley in 1967-69 and a Fellow of New College-Oxford in 1970.

Dawkins served as Charles Simonyi Chair of Public Understanding of Science at Oxford University from 1995-2008. In 2011 he joined the professoriate of the New College of the Humanities, founded by A.C. Grayling in London. He was elected a Fellow of the Royal Society of Literature in 1997 and a Fellow of the Royal Society of London for Improving Natural Knowledge in 2001.

The Selfish Gene, his first book, published in 1976, became an international best-seller. It was followed by The Extended Phenotype (1982), The Blind Watchmaker (1986), River Out of Eden (1995), Climbing Mount Improbable (1996), Unweaving the Rainbow (1998), A Devil’s Chaplain (2003) and The Ancestor’s Tale (2004). His iconoclastic book, The God Delusion, which he wrote with the public hope of turning believing readers into atheists, was published in 2006 to much acclaim.

He also produced several television documentaries decrying religion’s influence, including “Root of All Evil?” (2006) and “The Enemies of Reason” (2007). “The Genius of Charles Darwin” followed in 2008 and “The Meaning of Life” (2012) explored the implications of living without religious faith. In his memoir An Appetite for Wonder: The Making of a Scientist (2013), Dawkins chronicled his life up to publication of The Selfish Gene. A second memoir, Brief Candle in the Dark: My Life in Science, was published in 2015.

He founded the nonprofit Richard Dawkins Foundation for Reason and Science in 2006. It merged with the Center for Inquiry in 2016. The foundation finances research on the psychology of belief and religion, funds scientific education programs and supports secular charitable groups. Dawkins has advanced the concept of cultural inheritance or “memes,” also described as “viruses of the mind,” a category into which he places religious belief. He has also advanced the “replicator concept” of evolution.

A passionate atheist, Dawkins coined the memorable term “faith-heads” to describe certain religionists. His remarks in The Guardian (Feb, 6, 1999), “I’m like a pit bull terrier being released into the ring, as a spectator sport, to attack religious people” led to the nickname “Darwin’s pit bull.” His column for The Observer (Dec. 30, 2001) pointed out, “We deliberately set up, and massively subsidise, segregated faith schools. As if it were not enough that we fasten belief labels on babies at birth, those badges of mental apartheid are now reinforced and refreshed. In their separate schools, children are separately taught mutually incompatible beliefs.”

Dawkins was named the British Humanist Association’s 1999 Humanist of the Year in 1999 and received the International Cosmos Prize two years before that. In 2001 he was the recipient of an Emperor Has No Clothes Award from the Freedom From Religion Foundation but was unable to accept it in person because flights were grounded after 9/11. His written remarks accepting it are here. He accepted it in person in 2012 at the national convention in Portland, Ore.

He has been married three times and has a daughter, Juliet, born in 1984. Dawkins and Lalla Ward, who illustrated several of his books and other works, announced an “entirely amicable” separation in 2016 after 24 years of marriage. That same year he suffered a minor hemorrhagic stroke but reported later in the year that he had almost completely recovered.

PHOTO: By David Shinbone under CC 3.0.

"My respect for the Abrahamic religions went up in the smoke and choking dust of September 11th. The last vestige of respect for the taboo disappeared as I watched the ‘Day of Prayer’ in Washington Cathedral, where people of mutually incompatible faiths united in homage to the very force that caused the problem in the first place: religion. It is time for people of intellect, as opposed to people of faith, to stand up and say ‘Enough!’ "

— "Time to Stand Up," written for the Freedom From Religion Foundation (September 2001)

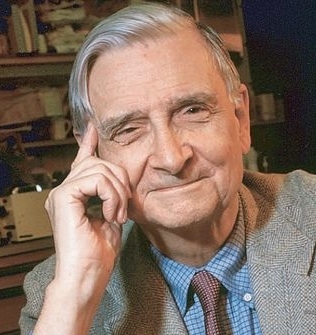

E.O. Wilson

On this date in 1929, biologist and author Edward Osborne Wilson was born in Birmingham, Ala. His father, Edward Osborne Wilson Sr., worked as an accountant. His mother, Inez Linnette Freeman, was a secretary. They divorced when he was 8. He had a nomadic childhood, mostly with his father, an alcoholic who would kill himself.

Wilson earned his B.S. and M.S. in biology from the University of Alabama and a Ph.D. in 1955 from Harvard, the same year he married Irene Kelley. They had a daughter, Catherine. He joined the Harvard faculty in 1956, where he retired in 2002 at age 73, although he published more than a dozen books after that.

Blinded in one eye by a fishing accident as a child, his research focus was in the field of myrmecology, the study of ants. He discovered the chemical means by which ants communicate. His books include The Insect Societies (1971) and The Ants (1990), co-written with Bert Holldobler, which won the 1991 Pulitzer Prize for nonfiction. Wilson’s On Human Nature won a Pulitzer in 1979.

Wilson is perhaps best known for his intellectual syntheses, often connecting evolution and biology to other disciplines. His 1967 book, The Theory of Island Biogeography, which develops the mathematics of how species evolve in geographically small habitats, is influential in the fields of ecology and practical conservation. He worked out the importance of habitat size and position within the landscape in sustaining animal populations.

In 1975 he published Sociobiology: A New Synthesis, which connected the evolution of social insects with other animals, including humans. At the time, the idea that human behavior is genetically influenced was very controversial and Wilson was criticized as racist and sympathetic to eugenics. During a 1978 lecture he had a pitcher of water poured on his head while the attacker exclaimed, “Wilson, you’re all wet.”

More recently, Wilson was criticized by Monica McLemore, an associate professor at UC-San Francisco, for espousing “theories fraught with racist ideas about distributions of health and illness in populations without any attention to the context in which these distributions occur.” She added that “what works for ants and other nonhuman species is not always relevant for health and/or human outcomes. For example, the associations of Black people with poor health outcomes, economic disadvantage and reduced life expectancy can be explained by structural racism, yet Blackness or Black culture is frequently cited as the driver of those health disparities. Ant culture is hierarchal and matriarchal, based on human understandings of gender. And the descriptions and importance of ant societies existing as colonies is a component of Wilson’s work that should have been critiqued. Context matters.” (Scienfic American, Dec. 29, 2021)

Wilson expanded on the ideas propounded in Sociobiology in On Human Nature (1978), which spawned the discipline of evolutionary psychology. While initially widely accepted with some enthusiasm, some aspects of evolutionary psychology research became even more controversial than Sociobiology, with the line between the two fields becoming more blurred.

Wilson’s parents were Southern Baptists though he was also raised by conservative Methodists. He abandoned Christianity before college, later describing himself as a “provisional deist” and agnostic. In On Human Nature, he argued that belief in God and rituals of religion are products of evolution. He disdained the tribalism of religion: “And every tribe, no matter how generous, benign, loving, and charitable, nonetheless looks down on all other tribes. What’s dragging us down is religious faith.”

In Esquire magazine (Jan. 5, 2009), Wilson said: “If someone could actually prove scientifically that there is such a thing as a supernatural force, it would be one of the greatest discoveries in the history of science. So the notion that somehow scientists are resisting it is ludicrous.”

He has been honored by the American Humanist Association twice, in 1982 with the Distinguished Humanist prize and again in 1999 as the Humanist of the Year. In 1990, he was awarded the Royal Swedish Academy of Science’s Crafoord Prize in ecology, considered the field’s highest honor. He died in Massachusetts at age 92. (D. 2021)

PHOTO by Jim Harrison under CC 2.5.

“So I would say that for the sake of human progress, the best thing we could possibly do would be to diminish, to the point of eliminating, religious faiths."

— Interview, New Scientist (Jan. 21, 2015)

Sean B. Carroll

On this date in 1960, Sean B. Carroll was born in Toledo, Ohio (not to be confused with cosmologist Sean M. Carroll). He earned a B.A. in biology from Washington University after only two years and graduated with a Ph.D. in immunology from Tufts Medical School in 1983 when he was 22. Carroll worked as a professor of genetics and molecular biology at the University of Wisconsin-Madison and an investigator at the University of Wisconsin’s Howard Hughes Medical Institute. He primarily studied evolutionary developmental biology, a relatively new field that focuses on the evolution of the development of organisms. Carroll, now an emeritus professor, has two sons with his wife Jamie.

Carroll is a strong advocate for evolution. When he was interviewed by Freethought Radio in 2008, Carroll stated that he often works with teachers who want to incorporate evolution into their curriculum and helps to develop high school lesson plans that include evolution. He has published three books about evolution: Endless Forms Most Beautiful: The New Science of Evo Devo (2005), The Making of the Fittest: DNA Evidence for Evolution (2006) and Remarkable Creatures: Epic Adventures in the Search for the Origins of Species (2009). He writes the “Remarkable Creatures” science column for The New York Times and was awarded the 2010 Stephen Jay Gould Prize for raising public awareness about the importance of evolution.

In 2007, Carroll wrote the article “God as Genetic Engineer,” which debunked author Michael Behe’s book about intelligent design, The Edge of Evolution (2007). When asked in a 2003 interview by Nature magazine what he wished the public understood better about science, Carroll responded, “The depth and breadth of evidence supporting scientific ideas: compared with, say, the absence of evidence in areas like astrology, UFOs and ghosts.”

PHOTO: By Jane Kitschier under CC 2.5.

"If a designer was designing us, either they're a terrible designer or they've got a great sense of humor, because we're carrying around all sorts of genes that don't work."

— Carroll, Freethought Radio interview (May 24, 2008)

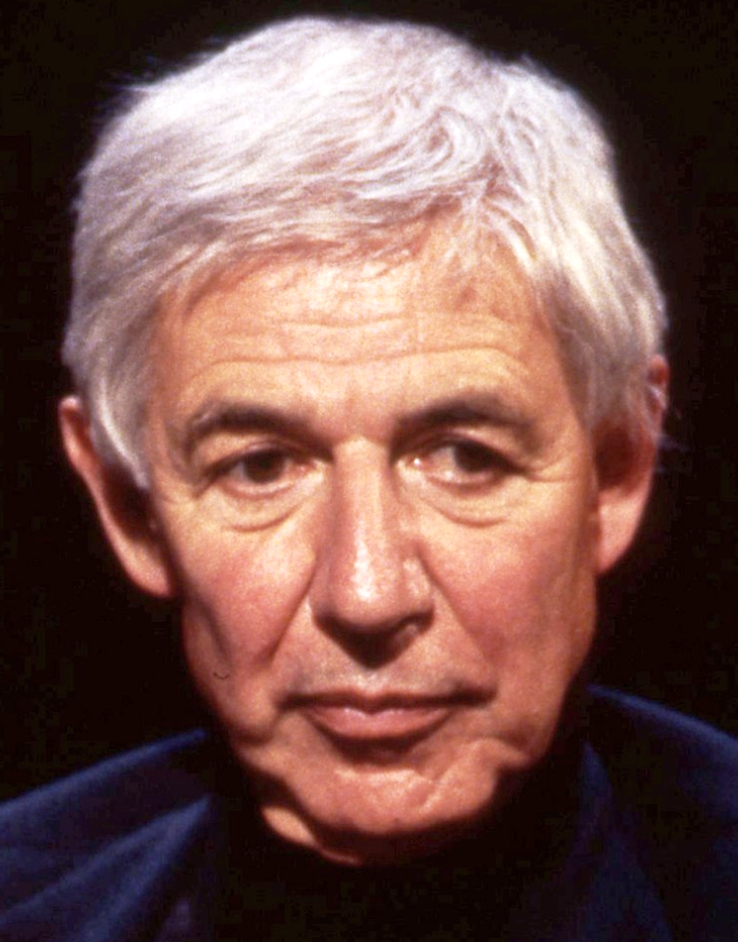

Lewis Wolpert

On this date in 1929, Lewis Wolpert was born into a Jewish family in Johannesburg, South Africa. He earned a degree in engineering from the University of Witwatersrand in 1950 and graduated from King’s College at the University of London with a Ph.D. in cell biology in 1961. He was a lecturer in zoology at King’s College from 1960-64 and became a professor of biology as applied to medicine at Middlesex Hospital Medical School 1966.

In 2010 he accepted emeritus status as a biology professor at University College London. He has several popular science books, including The Unnatural Nature of Science (1992), Malignant Sadness: The Anatomy of Depression (1999), Six Impossible Things Before Breakfast: The Evolutionary Origins of Belief (2006) and How We Live And Why We Die: The Secret Lives of Cells (2009). Wolpert was made a Commander of the Order of the British Empire in 1990.

After growing up Jewish, he became “a reductionist, materialist atheist,” according to an article in The Guardian (April 11, 2006). He wrote about his deconversion in Six Impossible Things Before Breakfast: “I was quite a religious child, saying my prayers each night and asking God for help on various occasions. It did not seem to help and I gave it all up around 16 and have been an atheist ever since.” In the book he states that religion arose from humans’ evolutionary predisposition to look for cause and effect relationships.

A vice president of the British Humanist Association, Wolpert has debated Christian apologist William Lane Craig about the existence of God, Christian astrophysicist Hugh Ross on whether there is a case for a creator and William Dembski on the topic of intelligent design.

He died at age 91 in England of COVID-related complications. (D. 2021)

PHOTO: Wolpert in 1994 under CC 4.0.

"I am committed to science and believe it to be the best way to understand the world. … I know of no good evidence for the existence of God."

— Wolpert, "Six Impossible Things Before Breakfast" (2006)

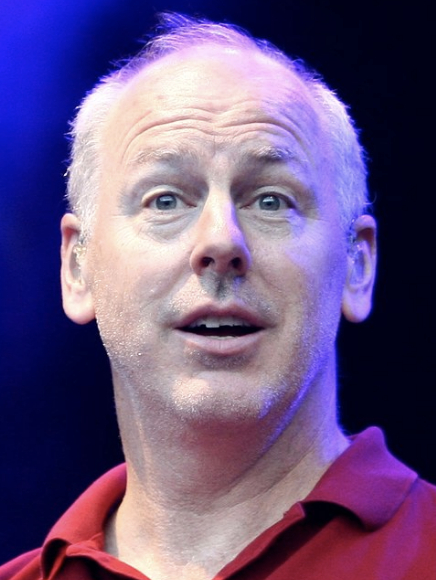

Greg Graffin

On this date in 1964, Gregory Walter Graffin was born in Racine, Wis. Graffin says he was raised in “an absolute vacuum of religion.” His father was a University of Wisconsin English professor. His parents divorced and he moved with his mother to Los Angeles when he was 11.

Graffin co-founded the punk rock band Bad Religion in 1980. The band released “Age of Unreason” in 2019, its 17th studio album. It was among the headliners at the 2012 Reason Rally in Washington, D.C., where Graffin sang the national anthem. He earned bachelor’s and master’s degrees from UCLA and a Ph.D. in zoology in 2003 from Cornell University. His thesis examined religion’s effect on humanity and included asking evolutionary biologists if they believed in God; almost 90% of those surveyed did not.

His books include Is Belief in God Good, Bad or Irrelevant? A Professor and Punk Rocker Discuss Science, Religion, Naturalism & Christianity (with Preston Jones), Evolution and Religion, Anarchy Evolution: Faith, Science, and Bad Religion in a World Without God (with Steve Olson) and Population Wars: A New Perspective on Competition and Coexistence. As of this writing he teaches a course on evolution for non-majors at Cornell between band tours.

Graffin calls himself a naturalist and says while he doesn’t believe in God, he’d rather not be called an atheist because “it’s not really saying much about how you came to that conclusion.” He received the Outstanding Lifetime Achievement Award in Cultural Humanism from Harvard University’s Humanist Chaplaincy in 2008.

He married Greta Maurer in 1988. After divorcing in 1996, he married Allison Kleinheinz in 2008. He has a daughter, Ella, and a son, Graham, with Greta.

PHOTO: Graffin in Germany with Bad Religion at the Taubertal Festival 2013; photo by Antje Naumann under CC 3.0.

"If you can believe in God, then you can believe in anything. It's a gang mentality."

— Graffin, wired.com interview (November 2006)