March 7

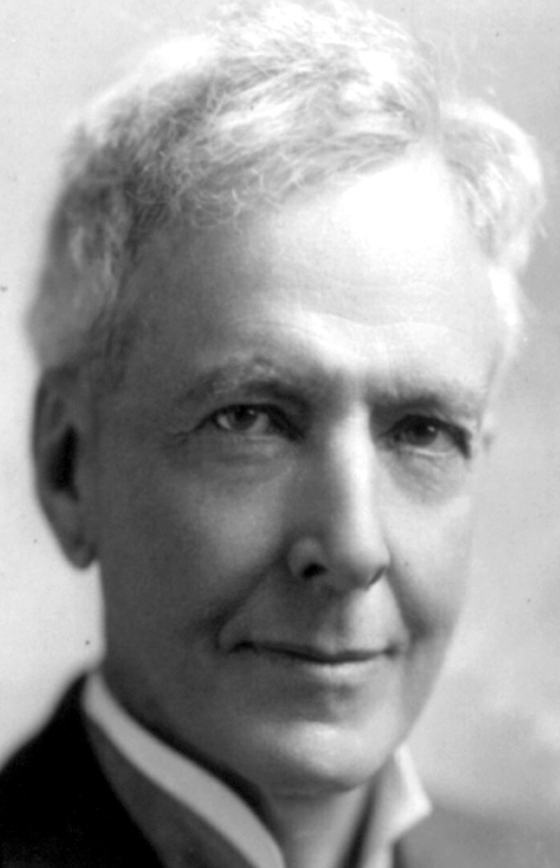

Luther Burbank

On this date in 1849, Luther Burbank was born in Lancaster, Mass. He found fame early when he single-handedly saved U.S. potato crops from the deadly blight by cultivating russet potatoes. The Burbank Russett is the most widely cultivated potato in the U.S. While running Burbank’s Experimental Farms in Santa Rosa, Calif., he produced more than 800 new varieties of fruits and plants.

Shaken by the Scopes “monkey” trial, Burbank wrote, “And to think of this great country in danger of being dominated by people ignorant enough to take a few ancient Babylonian legends as the canons of modern culture. Our scientific men are paying for their failure to speak out earlier. There is no use now talking evolution to these people. Their ears are stuffed with Genesis.”

In 1926, an interview about his freethought views appeared in the San Francisco Bulletin in which he declared “I am an infidel today,” adding,” I am a doubter, a questioner, a skeptic. When it can be proved to me that there is immortality, that there is resurrection beyond the gates of death, then will I believe. Until then, no.” He was inundated with mostly critical letters, which he felt he had to reply to personally. Friend and biographer Wilbur Hale attributed Burbank’s death at age 77 after suffering a heart attack to the exertion of his replies: “He died, not a martyr to truth, but a victim of the fatuity of blasting dogged falsehood.”

A crowd estimated at 10,000 came to his memorial and heard the openly atheistic tribute by Judge Lindsay of Denver. California still celebrates Burbank’s birthday as Arbor Day, planting trees in his memory. He married twice: to Helen Coleman in 1890, which ended in divorce in 1896, and to Elizabeth Waters in 1916. He had no children. (D. 1926)

“The idea that a good God would send people to a burning hell is utterly damnable to me. I don’t want to have anything to do with such a God.”

“I am an infidel today.”— Burbank interview in the San Francisco Bulletin (Jan. 22, 1926)

Alan Hale

On this date in 1958, Alan Hale, the co-discoverer in 1995 of Comet Hale-Bopp, was born in Tachikawa, Japan, where his father was in the U.S. Air Force. He grew up in Alamogordo, N.M., and graduated with a B.S. in physics in 1980 from the U.S. Naval Academy in Annapolis, Md. He left the Navy in 1983 and began working at the Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena, Calif., as an engineering contractor for the Deep Space Network.

While at the JPL he worked on spacecraft projects, including the Voyager 2 encounter with the planet Uranus in 1986. He then returned to New Mexico and earned advanced astronomy degrees, including a doctorate, at New Mexico State University in Las Cruces. In 1993 he founded the Southwest Institute for Space Research (now called the Earthrise Institute, where he is president).

Besides his research activities, Hale is an outspoken advocate for improved scientific literacy in our society and for better career opportunities for current and future scientists. He’s written for such publications as Astronomy, the International Comet Quarterly, the Skeptical Inquirer, Free Inquiry and the McGraw-Hill Yearbook of Science and Technology. He’s the author of Everybody’s Comet: A Layman’s Guide to Comet Hale-Bopp (High-Lonesome Books, 1996) and is a frequent public speaker on astronomy, space and other scientific issues.

Hale was a featured speaker at the FFRF’s 20th annual convention in Tampa, Fla., in 1997. The speech came in the aftermath that March of the suicides of 39 men and women who were part of the Heaven’s Gate UFO cult in Rancho Santa Fe, Calif. After claiming that a spaceship was trailing the Comet Hale-Bopp, cult leader Marshall Applewhite convinced his followers to kill themselves so their souls could board the spacecraft.

The members killed themselves in an orderly and disciplined fashion, over several days, in three teams, by taking a strong barbiturate with vodka, followed by a plastic bag over the head. All wore black clothes and brand-new Nike running shoes. All had packed a suitcase and had ID cards, a $5 bill and three quarters.

Hale called the death pact and other religion-fostered violence “another victory for ignorance and superstition.”

PHOTO: Courtesy of Alan Hale

“Oh, I have plenty of biases, all right. I’m quite biased toward depending upon what my senses and my intellect tell me about the world around me, and I’m quite biased against invoking mysterious mythical beings that other people want to claim exist but which they can offer no evidence for.”

“By telling students that the beliefs of a superstitious tribe thousands of years ago should be treated on an equal basis with the evidence collected with our most advanced equipment today is to completely undermine the entire process of scientific inquiry.”

“And one more thing: In your original message you identified yourself as an elementary school teacher. If you are going to insist on holding to a creationist viewpoint, then please stay away from my children. I want my kids to learn about ‘real’ science, and how the ‘real’ world operates, and not be fed the mythical goings-on in the fantasy-land of creationism.”

— Series of e-mails starting Jan. 14, 1997, retrieved from https://infidels.org/kiosk/article/email-conversation-with-a-creationist/

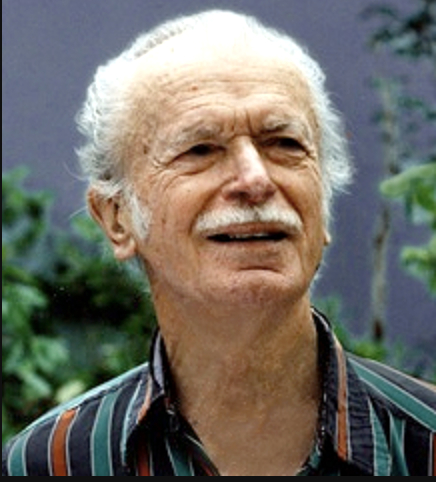

Maurice Ravel

On this date in 1875, Joseph Maurice Ravel, composer, pianist and conductor, was born in the Basque town of Ciboure, France. His father, Pierre-Joseph Ravel, was an educated engineer, inventor and manufacturer. His mother, Marie (née Delouart) Ravel, was born to an unwed mother and was barely literate. She was also a freethinker, a trait inherited by Maurice, who was always politically and socially progressive as an adult, according to musicologist and Ravel scholar Arbie Orenstein.

He was admitted to France’s premier music academy, the Conservatoire de Paris, winning first prize in the school’s piano competition in 1891. He was expelled in 1895 due to differences with faculty conservatives but was readmitted two years later and studied composition with Gabriel Fauré. He was later forced out again after clashing with Conservatoire Director Théodore Dubois, who deplored Ravel’s musical and political progressivism.

Making his way as an orchestral arranger and composer, he was often associated with his contemporary Claude Debussy as an impressionist, though neither liked the term. He liked to experiment with musical form, as is evident in “Boléro” (1928), his best-known work. “Boléro” is a one-movement orchestral piece originally composed as a ballet that repeats its main melody 18 times by solo or combinations of instruments. The duration varies depending on the tempo but typically is about 16 minutes. When Toscanini conducted it faster, Ravel objected, resulting in hard feelings. “When I play it at your tempo, it is not effective,” Toscanini said. To which Ravel supposedly replied, “Then do not play it.”

Ravel, a master of orchestration, worked at a slower pace than many of his contemporaries. Among his 85 works, many incomplete, are pieces for piano, chamber music, two piano concertos, ballet music, two operas and eight song cycles. He wrote no symphonies or church music. He was among the first to realize the potential of recording music. According to a 1914 article in the French magazine Comoedia illustré, there’s “a notable absence of religious forms or references” in his works. “His habitual inspiration came from nature, from fairy tales and folk songs, and from classical and Oriental legends. Nor was he always sympathetic to the religious works of other composers.”

Although he never married and was childless, Ravel liked children and wrote piano music they could play and reflected their world. He wrote “Ma Mère l’Oye” (Mother Goose), subtitled “cinq pièces enfantines” in 1910 as a duet and dedicated it to his students, Mimie Godebska and her brother Jean. “It was he who made me read the Fioretti (Little Flowers) of St. Francis of Assisi. Although he was a confirmed atheist, he adored this book, and I was so amazed by it that I used to imagine it being set to music — by Ravel,” wrote Mimie Godebska Blacque-Belair in 1938.

Ravel started to suffer from neurological impairment in the early 1930s, which affected his piano playing, touring and conducting. The cause was never determined but may have been dementia, Alzheimer’s or Creutzfeldt–Jakob disease. He died at age 62 and was buried next to his parents with no religious ceremony. (D. 1937)

PHOTO: Ravel at age 50.

“What you write to me about the benefits of religion, we have spoken of it with Pierrette Haour, an atheist like me.”

— Ravel letter in 1920 to Ida Godebska, cited in "Maurice Ravel: lettres, écrits, entretiens" (letters, writings, interviews), Arbie Orenstein, ed., (1989)

Lucy Parsons

On this date in 1942, Lucy Parsons — labor organizer, social reformer and anarchist — died in Chicago. Born Lucia Carter, the exact date of her birth in Virginia beyond the year 1851 is unknown. Her mother was a slave and it’s suspected that her father was a physician and slave owner named Thomas Taliaferro who moved in 1862 or 1863 to Texas with Lucia, her mother and brother and another young woman. (Goddess of Anarchy: The Life and Times of Lucy Parsons, American Radical, Jacqueline Jones, 2017)

Racially mixed, she claimed Hispanic and indigenous heritage, denying any Black ancestry, possibly due to the stigma attached. She had a child with an older man but the paternity was uncertain, according to biographer Jones. It may have been Oliver Benton, a former slave owner who considered Lucia his wife, but it’s likely they never married, despite Benton’s claim they were.

Some sources say that in 1872 when she was 21 and he was 27, she married Albert R. Parsons, a white newspaper editor active in Republican politics, though there is no official record of the marriage. Now going by Lucy Parsons and living in Chicago, she gave birth to a son, Albert (b. 1879), and a daughter, Lulu (b. 1881).

The Parsons became heavily involved in the socialist labor movement. On May 4, 1886, her husband Albert spoke to a crowd of about 25,000 people about peaceful negotiations in the movement. Later that day, there was a bombing with eight people killed, which became known as the Haymarket Affair. Albert and three others were accused, prosecuted and executed.

Parsons became widely known for her incendiary speeches and was arrested and jailed many times. In 1892 she founded the newspaper Freedom: A Revolutionary Anarchist-Communist Monthly, which focused on labor organizing and Black liberation. In 1905 she was the second woman to join the Industrial Workers of the World (aka the Wobblies) and edited its newspaper The Liberator.

She worked with the International Labor Defense to provide support to 9 African-American teens known as the Scottsboro Boys, who were falsely accused in 1931 of raping two white women on a train near Scottsboro, Ala. One of the women recanted her allegations and the death penalty was dropped for the defendants, who collectively served over 100 years in prison.

Parsons continued to give fiery speeches in Chicago’s Bughouse Square into her 80s, where she inspired Louis “Studs” Terkel. After her death, police seized her library of over 1,500 books and all of her personal papers.

“For the most part, Parsons avoided using religion as a vehicle of uplift,” wrote Willie J. Harrell in the Journal of International Women’s Studies. (Vol. 13 #1, March 2012) “When religion did appear in her anarchist discourse, it was more political than religious. ‘Let us sink such differences as nationality, religion, politics … There is no power on earth that can stop men and women who are determined to be free at all hazards’ [Parsons asserted].”

“The ‘all-wise’ and ‘all-merciful’ God is adding his quota to the sum of human wretchedness, for he is having the ‘windows of heaven’ all thrown open and pouring down floods upon the bowed heads of his most devout worshipers — the Negroes of the South and the farmers of the West — in the most awful devastation and death!” (Lucy Parsons: Freedom, Equality & Solidarity, Writings & Speeches, 1878-1937, 2003)

Parsons died in an accidental house fire at age 91 and was buried near her husband at Waldheim Cemetery near the Haymarket Martyrs’ Monument in Forest Park, Ill. (D. 1942)

PHOTO: Parsons in 1886 at about age 35.

“We have heard enough about a paradise behind the moon. We want something now. We are tired of hearing about the golden streets of the hereafter. What we want is good paved and drained streets in this world.”

— "Lucy Parsons: Freedom, Equality & Solidarity, Writings & Speeches, 1878-1937" (ed. Gale Ahrens, 2003)

Jo Kotula

On this date in 1910, illustrator Josef “Jo” Kotula was born in Poland. He emigrated at 6 months of age with his parents to the U.S. His father worked as a Pennsylvania coal miner. Self-taught as an artist, Kotula became widely known for aviation art.

“Jo was a master of handling sunlight on bare aluminum,” according to the American Society of Aviation Artists, which inducted him into its Hall of Fame in New Jersey in 1999. His cover illustrations for Model Airplane News started in 1932 and continued for 38 years. His art also adorned the boxtops of model airplane kits.

He illustrated U.S. Air Force training manuals, acquired a private pilot’s license in 1936 and often delivered his work by air to clients around the country. His talent was such that it appeared in national magazines like the Saturday Evening Post, Collier’s, Newsweek and Popular Science.

He lived in the Midwest and Texas during early adulthood and met Charline Kirkpatrick in San Antonio. They married less than a month after their first date and moved east in 1931. They would have four daughters during their 66-year marriage — Jo Ann, Nella, Lynn and Orin — and a son, Kirk Patrick.

The Kotulas were early, heavily involved FFRF supporters and served as co-vice presidents of FFRF East in New Jersey. In 1954 they helped organize the Morristown Unitarian Fellowship and put up their house as collateral to borrow the money to buy a stately brick building to house the congregation. At a 1994 FFRF dinner there honoring them for their activism, Jo called the building “a haven for refugees from orthodoxy. We are here, we feel, not so much in our honor, but to celebrate, to dedicate our freedom of inquiry, our right to a healthy skepticism, to explore every avenue of thought open to scientific probing.”

Both were active as advocates for women’s reproductive rights, civil rights and immigrants’ rights, while opposing nuclear proliferation and the Vietnam War. After Charline’s death in 1995, FFRF specified that some of its annual Freethought Heroine awards be given in her memory. Jo died three years later at age 88. (D. 1998)

“It does appear that each of our thousands of denominations believes that its principles, its tenets, should have official recognition put forth by our secular government, imprinted on our currency, proclaimed in ceremonies with ringing bells from church steeples!”

— Kotula remarks at New Jersey recognition dinner (Freethought Today, May 1994)