February 15

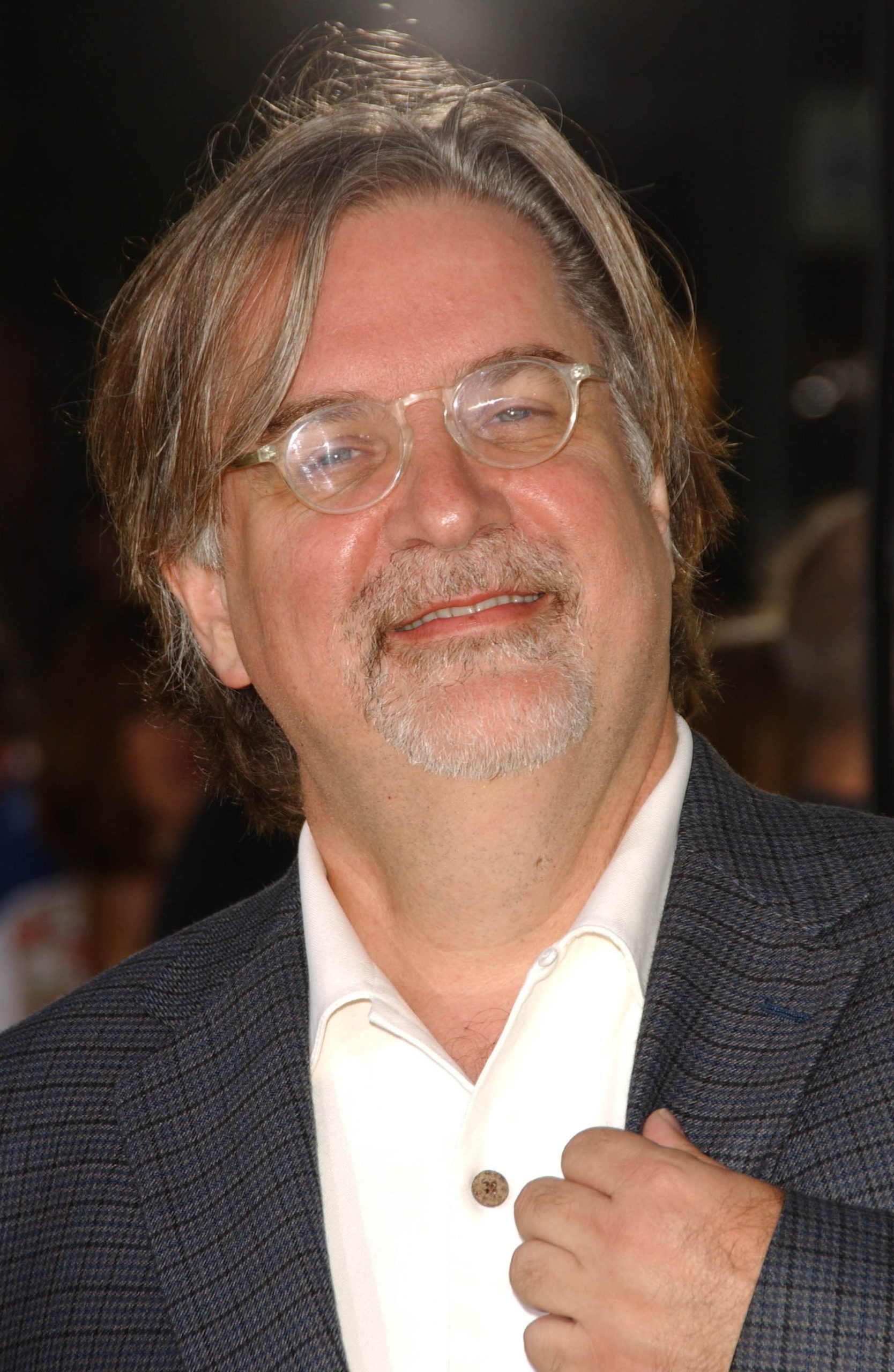

Matt Groening

On this date in 1954, Matthew Abraham Groening was born in Portland, Ore., to Homer Groening, an advertising agent and amateur cartoonist, and Margaret Wiggum. Groening was one of four children. Best known as the creator and executive producer of the TV program “The Simpsons,” Groening’s career started when he moved to Los Angeles after graduating from Evergreen State College and began selling Xeroxed copies of his comic strip “Life in Hell,” an irreverent look at a broken life. This original strip was subsequently syndicated, became successful and eventually caught the attention in 1987 of James L. Brooks, executive producer of “The Tracey Ullman Show.”

Looking for a “filler” in the show, Brooks asked Groening to create animated TV “shorts” which became “The Simpsons,” the longest-running animated series in TV history. Groening later created another successful animated TV show, the fantasy-based “Futurama.” In 1993 he formed and became publisher of the “Bongo Comic Group,” overseeing the “Simpsons Comics,” “Itchy & Scratchy Comics,” “Bartman,” “Radioactive Man,” “Lisa Comics” and “Krusty Comics.”

In an IMDB.com mini biography by Kevin Newcombe, Groening is quoted as saying: “Cartooning is for people who can’t quite draw and can’t quite write. You combine the two half-talents and come up with a career.” He produced the adult animated fantasy sitcom “Disenchantment” for Netflix in 2018. Twenty more episodes were scheduled to air between 2020 and 2021.

Groening and Deborah Caplan married in 1986 and had two sons, Homer (who goes by Will) and Abe. They divorced in 1999 and Groening married Argentine artist Agustina Picasso in 2011. They have a son, Nathaniel, and twin daughters, Luna and India.

“Technically, I’m an agnostic, but I definitely believe in hell — especially after watching the fall TV schedule.”

— New York Times interview (Dec. 17, 1998)

Galileo Galilei

On this date in 1564, Galileo Galilei was born in Pisa, Italy. Galileo was appointed professor of mathematics at the University of Padua, where he lectured for 18 years. Galileo pioneered the experimental scientific method, building a thermoscope, constructing a geometrical and military compass and building an improved telescope. His observations of the satellites of Jupiter, sunspots, mountains and valleys on the moon made him a celebrity, but his Copernican views were investigated and condemned by the Catholic Church.

Diplomatically seeking church permission, he published “The Assayer,” (1623) describing his scientific method, which was tactfully dedicated to Pope Urban VIII. It took Galileo nearly two years to persuade the church to permit him to publish “Dialogue on the two Chief Systems of the World — Ptolemaic and Copernican” (1632), in which he wrote about impetus, momentum and gravity. The Holy Office banned the book, summoning the frail scientist to Rome for trial. Galileo was ordered to retract his theory and was condemned to house arrest for the rest of his life. Three hundred and fifty years after his death, the Catholic Church “forgave” Galileo. D. 1642.

"I have been … suspected of heresy, that is, of having held and believed that the Sun is the center of the universe and immovable, and that the earth is not the center of the same, and that it does move. … I abjure with a sincere heart and unfeigned faith, I curse and detest the said errors and heresies, and generally all and every error and sect contrary to the Holy Catholic Church."

— Galilei's "Recantation" (June 22, 1633)

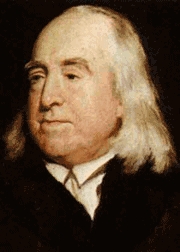

Jeremy Bentham

On this date in 1748, Jeremy Bentham was born in London. The great philosopher, utilitarian, humanitarian and atheist began learning Latin at age 4. He earned his B.A. from Oxford by age 15 or 16 and his M.A. at 18. His Rationale of Punishments and Rewards was published in 1775, followed by his groundbreaking utilitarian work Introduction to the Principles of Morals and Legislation. Bentham propounded his principle of “the greatest happiness of the greatest number.” He worked for political, legal, prison and educational reform.

Inheriting a large fortune from his father in 1792, Bentham was free to spend his remaining life promoting progressive causes. The renowned humanitarian was made a citizen of France by the National Assembly in Paris. In published and unpublished treatises, Bentham extensively critiqued religion, the catechism, the use of religious oaths and the bible. Using the pen name Philip Beauchamp, he co-wrote a freethought treatise, Analysis of the Influence of Natural Religion on the Temporal Happiness of Mankind (1822). D. 1832.

"No power of government ought to be employed in the endeavor to establish any system or article of belief on the subject of religion.”

“[I]n no instance has a system in regard to religion been ever established, but for the purpose, as well as with the effect of its being made an instrument of intimidation, corruption, and delusion, for the support of depredation and oppression in the hands of governments."

— Bentham, "Constitutional Code," "The Collected Works of Jeremy Bentham," eds. F. Rosen and J. H. Burns (1983)

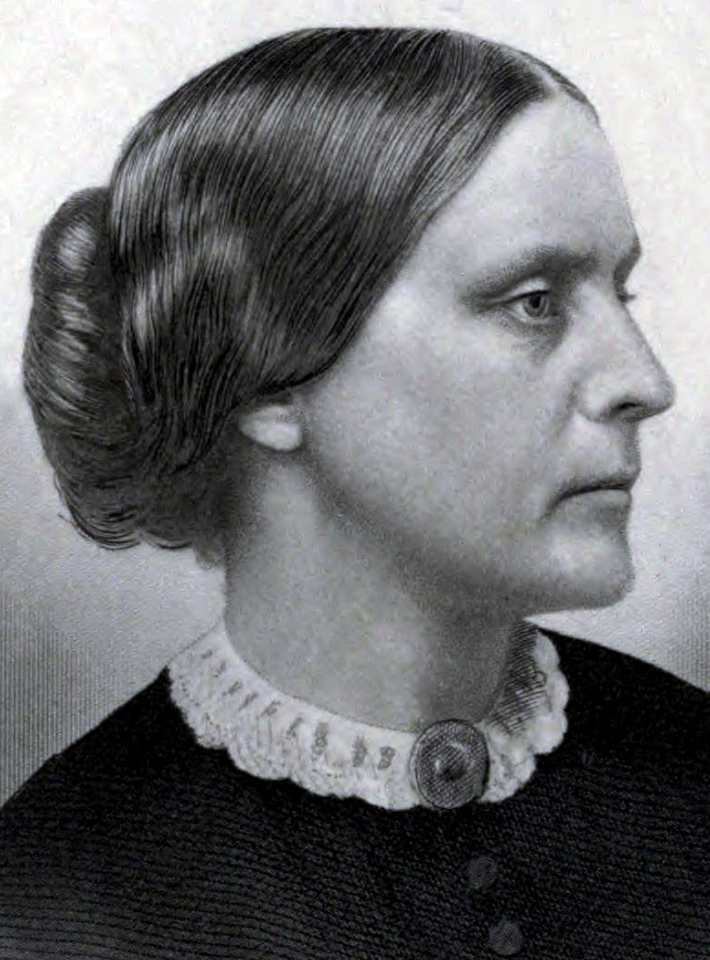

Susan B. Anthony

On this date in 1820, Susan Brownell Anthony was born in Massachusetts. She taught school from ages 15 to 30 before devoting her life to reform. She and Elizabeth Cady Stanton, starting in 1850, became lifelong feminist collaborators. The tireless crusader spent 30 years campaigning for women’s suffrage. Raised Quaker, she became a Unitarian but at the end of her life was an agnostic. Anthony’s professed “creed” was that of “the perfect equality of women,” according to Stanton.

While privately scolding Stanton for editing the controversial Woman’s Bible, Anthony publicly defended her: “I think women have just as much a right to interpret and twist the Bible to their own advantage as men always have interpreted and twisted it to theirs.” (Interview in the Rochester Democrat and Chronicle, quoted in The Life and Work of Susan B. Anthony.) She also confessed, “But while I do not consider it my duty to tear to tatters the lingering skeletons of the old superstitions and bigotries, yet I rejoice to see them crumbling on every side.”

Her biographer Ida Husted Harper wrote that after Anthony visited a poor mother of six in Ireland in 1883, Anthony noted that “the evidences were that ‘God’ was about to add a No. 7 to her flock” and later commented, “What a dreadful creature their God must be to keep sending hungry mouths while he withholds the bread to fill them!”

There is no record she ever had a serious romance despite receiving marriage offers and would answer journalists’ questions with statements like “It always happened that the men I wanted were those I could not get, and those who wanted me I wouldn’t have.” To another she answered, “I never found the man who was necessary to my happiness. I was very well as I was.” She had no desire to “give up my life of freedom to become a man’s housekeeper.”

But according to Sted Mays, writing in the Gay & Lesbian Review, Anthony felt compelled to create a conventional public persona and made excuses for her unmarried status in order to hide her same-sex attractions: “She talked in interviews about not wanting to be trapped in a male-dominated relationship. But the real reason she never had a serious relationship with a man was that her passions were directed toward other women.” (“Stop Straightwashing Susan B. Anthony,” Feb. 10, 2020)

She died of heart failure at age 86 at her home in Rochester, N.Y. (D. 1906)

“I could not dash her faith with my doubts, nor could I pretend a faith I had not; so I was silent in the dread presence of death.”

— Anthony contemplating her sister on her deathbed, "The Life and Work of Susan B. Anthony, Vol. 2" by Ida Husted Harper (1898)

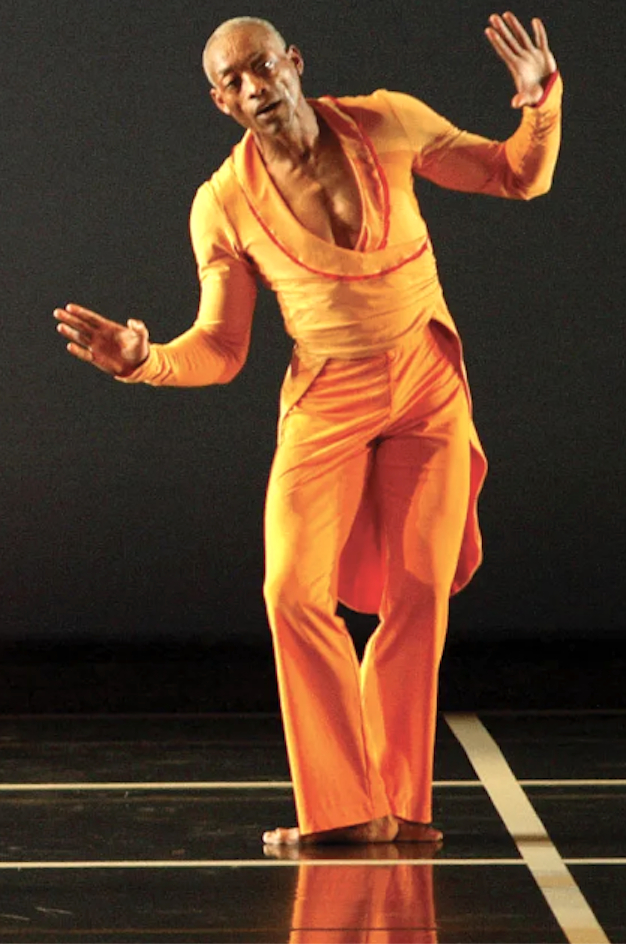

Bill T. Jones

On this date in 1952, William Tass “Bill T.” Jones was born in Bunnell, Fla., the 10th of 12 children born to Estella (Edwards) and Augustus Jones, migrant farm workers. The family followed the crops north and settled when he was 3 in Wayland, N.Y. “I am a child of potato pickers who wept at the Civil Rights Act of 1964, because they knew what it meant,” Jones later said. “They knew what had been denied them before.” (The Guardian, June 11, 2004)

He starred in track in high school and participated in drama and debate. After graduation he enrolled at the State University of New York at Binghamton, where he studied classical ballet and modern dance and took classes in west African and African-Caribbean dancing. Binghamton was where he fell in love with Arnie Zane. Their personal and professional relationship lasted until Zane’s death from AIDS in 1988.

With Lois Welk and Jill Becker, they formed American Dance Asylum in 1974 and began emphasizing a partnering technique called contact improvisation. Jones created a number of solo pieces during this period and performed in New York City. Interested in living in an area more supportive of the arts and of an interracial gay couple, he and Zane moved in 1979 to Rockland County just outside the Bronx.

Their duets featured photography, singing, and spoken dialogue with a political and social focus and acknowledgement of their personal relationship. A trilogy they created in 1979-81 — “Blauvelt Mountain,” “Monkey Run Road” and “Valley Cottage” — broke choreographic ground.

They formed the Bill T. Jones/Arnie Zane Dance Company in 1982, recruiting nontraditional performers representing different body sizes, shapes and colors. “Jones, a choreographic provocateur, presents his ideas about identity, art, race, sexuality, nudity, power, censorship, homophobia and AIDS-as-chemical-warfare with a streetwise, in-your-face attitude,” said a 1998 entry in the “International Encyclopedia of Dance.”

“Last Supper at Uncle Tom’s Cabin/The Promised Land” (1990) explored differences not only in body shapes but attitudes, race and sexuality. It was also about Jones’ conflict with faith, despite growing up in a devoutly Christian home. He has called it “a dialogue with my mother’s faith.” (Which never included 52 nude bodies dancing à la the piece’s fifth and final section.) “Last Supper” questioned how God could allow the cruelties of slavery and AIDS to happen. Zane had died in 1988 at age 39 of AIDS-related lymphoma. Jones’ piece “Absence” evoked his memory.

In an interview with Jeffrey Brown (Oct. 8, 2021) for “News Hour” on PBS, he told Brown “I’m an atheist.”

“Still/Here” (1995), a major midcareer work, was controversial in some quarters. It was “a meditation about mortality in which Jones incorporated the movements of terminally ill people whom he’d met in the free dance workshops he’d set up for them, the patients becoming, in a sense, collaborators.” (New York Times, June 6, 2016) New Yorker dance critic Arlene Croce called it “victim art” and refused to see the production.

With over 120 works for his own company, Jones has also choreographed for Alvin Ailey American Dance Theater and numerous other companies. “Arguably the most written-about figure in the dance world of the last quarter century, Jones is inarguably the most broadly laureled, with a National Medal of Arts and a Kennedy Center Honor and Tony Awards and a Dorothy & Lillian Gish Prize and a MacArthur Fellowship and, without hyperbole, scores more.” (Ibid.) His memoir “Last Night on Earth” was published in 1995.

Jones is married to designer and creative director Bjorn Amelan, a French national raised in Haifa, Israel, and several European countries. They have been together since 1993, when he started designing many of Jones’ sets.

"I am a humanist, as all Christians are supposed to be. For me, the bottom line is commonality. It is the only thing I accept. I don't even know if a soul exists. But I do know there is a condition called humanity that we are a part of, with wonderful potential for good and evil. I believe in limited free will. God? I believe there is an intelligence in the universe, but I don't believe in absolute morality, in sin."

— Interview, Los Angeles Times (March 10, 1991)