December 26

Steve Allen

On this date in 1921, entertainer Stephen Valentine Patrick Allen was born in New York City to Carroll and Isabelle {Donohue) Allen, who were vaudeville performers. His father died when he was an infant and Allen was raised mostly by his mother’s Irish-Catholic family in Chicago. He dropped out of Arizona State Teachers College during his sophomore year to go into radio, then served during World War II before returning to radio work.

Allen became a household name as the original host of the NBC “Tonight Show.” He portrayed Benny Goodman in the movie “The Benny Goodman Story,” recorded 40 albums as a jazz pianist, composed over 8,000 songs, wrote 54 books and hosted the PBS series “Meeting of Minds” (1977-81). Great minds from the past met on the groundbreaking show, which featured at least its share of freethinkers. Allen was also a lyricist whose songs include “This Could Be the Start of Something Big.”

He was a regular panelist in the early 1950s on “What’s My Line?” before hosting “The Steve Allen Show” in 1953 on a New York station. It was renamed “Tonight!” in 1954 and started its historic run on the full NBC network. Allen was host until succeeded in 1957 by Ernie Kovacs. He continued to host variety and comedy shows in the coming years. He last guest-hosted “The Tonight Show” in 1982 and made a final “Tonight” appearance in 1994 for the show’s 40th anniversary broadcast.

He was married for 46 years to actress Jayne Meadows after being married to Dorothy Goodman from 1943-52. They had three sons, and he and Meadows had another son. When his son Brian (with Dorothy) joined a cult in the 1970s, Allen wrote Beloved Son: A Story of the Jesus Cults (1982). Allen became aware of the distressing nature of the bible while reading Gideon Bibles left in hotel rooms. In Steve Allen on the Bible, Religion & Morality (1990), he mused: “I believe it is the imposition of a dictatorship that increasing numbers on the Christian Right now wish to construct in the United States.”

Working with Paul Kurtz, publisher of Prometheus Books, Allen published 15 books, including Dumbth: The Lost Art of Thinking with 101 Ways to Reason Better and Improve Your Mind. In 2011 he was selected for inclusion in the Committee for Skeptical Inquiry’s Pantheon of Skeptics.

Allen died at age 78 in Encino, Calif., from a ruptured blood vessel caused by chest injuries he didn’t realize he had sustained in a minor traffic accident earlier in the day. (D. 2000)

“The proposition that the entire human race — consisting of enormous hordes of humanity — would be placed seriously in danger of a fiery eternity characterized by unspeakable torments purely because a man disobeyed a deity by eating a piece of fruit offered him by his wife is inherently incredible.”

— "Steve Allen on the Bible, Religion & Morality" (1990)

James Mercer

On this date in 1970, musician James Russell Mercer was born in Honolulu, Hawaii. He frequently moved with his family because his father was in the Air Force. Mercer has been an atheist since he was about 10, breaking away from his family’s Catholic faith. “There was a half-assed attempt to give me religion,” Mercer said. “They sent me to a Catholic Sunday school … and they showed me videos of the end of the world. It seemed like a comic book and Satan was just another villain, like Lex Luthor or something. It seemed totally preposterous.” (Magnet magazine, No. 86.)

Mercer’s first break as a musician came with the album “Your Land is Here, It’s Time to Return” with his band Flake Music. This led them to go on tours with bands such as Modest Mouse. Mercer is well known as lead singer and songwriter of the indie band The Shins, which formed in 1996. The Shins’ 2007 album “Wincing the Night Away” was nominated for a Grammy for Best Alternative Music Album and peaked at number two on the Billboard 200 album chart.

Mercer’s indie rock project was named Broken Bells. His co-member was Brian Burton, known as Danger Mouse, who, along with Cee Lo Green, made up the band Gnarls Barkley. Broken Bells’ debut self-titled album was released in 2010 and peaked at number two on the Billboard Independent Albums chart. Mercer’s music has been featured in many movies, including “Garden State” (2004) and “The Amazing Spider-Man” (2012).

He married designer/decorator Marisa Kula in 2006. They have three daughters. Mercer said in a 2012 SPIN interview, “There’s no real reason for me to be so obsessed with trying to understand the true nature of things. You can live a perfectly happy life being utterly confused and not knowing.”

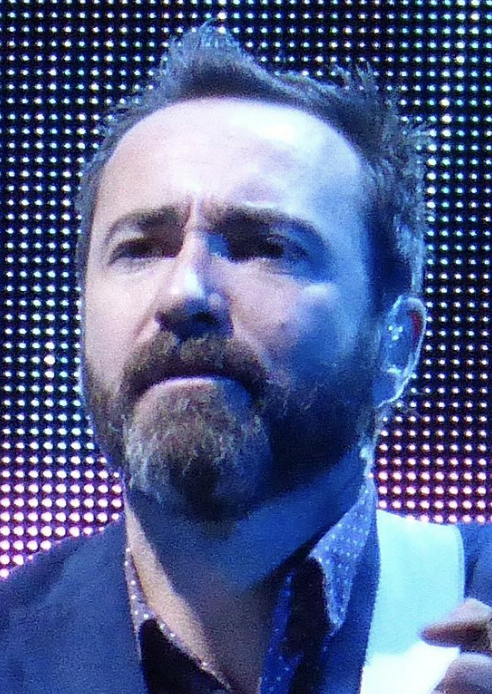

PHOTO: Mercer performing with Broken Bells in 2014 at Coachella. CC 1.0

“I do like talking with friends about big concepts, you know, the stuff that will ruin a party. To me, the party hasn’t begun until we’re talking about the nonexistence of God.”

— Mercer interview with SPIN magazine (February 2012)

David Sedaris

On this date in 1956, author and humorist David Raymond Sedaris was born near Binghamton in Johnson City, N.Y., to Sharon (née Leonard), an Anglo-American, and Louis Sedaris. His father, an IBM engineer, was born in the U.S. to Greek Orthodox immigrants.

David’s Greek grandmother “kept a crucifix the size of a hand mirror in her bedroom and kissed it until her lips wore the plating off Jesus’ stomach. Cried when she saw Billy Graham on TV, even though she didn’t understand what he was saying. ‘Jesus blessie,’ she’d whisper, crossing herself whenever we passed a church, any church. Tie two sticks together and her eyes would water. My father had maybe a third of her faith, and his children, for whatever reason, none. (“The Hem of His Garment,” The New Yorker, Sept. 2, 2024)

He grew up in a suburb of Raleigh, N.C., the second eldest of four sisters and a brother. His sister Tiffany was plagued by mental illness and killed herself in 2013 at age 49. The last time he saw her, he shut his door as she stood outside it after a book reading because of a disagreement they’d had earlier.

“[W]e never spoke Greek at home, so I never understood what they were saying [in church]. I didn’t grow up with the idea of a punishing God, just a really dull one. So my idea of death didn’t really include an afterlife. The first person I knew to die was my grandfather and no one said, ‘He’s in heaven now.’ Every time I hear that, I just want to throw up. … It just seems so implausible to me. I don’t think my mother would necessarily want to be with my father for an eternity. The time on Earth was more than enough.” (Sydney Morning Herald interview, Oct. 14, 2022)

He attended Western Carolina University and Kent State University in Ohio, dabbled in visual and performance art and writing before moving to Chicago in 1983 and graduating from the School of the Art Institute of Chicago.

Sedaris, slight of stature at 5-foot-5, massively impressed radio host Ira Glass while reading in a Chicago club a diary he had kept since 1977. Success on Glass’ show and in other venues led to his National Public Radio debut in 1992 reading his essay titled “Santaland Diaries” describing his experiences as a Christmas elf in Macy’s in New York.

The New York Times called the essay “a minor phenomenon” and he started recording regular NPR segments, signed a two-book deal with Little, Brown and writing essays for The New Yorker and Esquire. Several essay collections followed. “Me Talk Pretty One Day,” recounting life in Paris while learning French, won the 2001 Thurber Prize for American Humor. “Dress Your Family in Corduroy and Denim” reached No. 1 on The New York Times Nonfiction Best Seller List in June in 2004.

Essays and articles followed into the 2020s. In “Calypso” (2018), he wrote, “Increasingly at Southern airports, instead of a ‘good-bye’ or ‘thank-you,’ cashiers are apt to say, ‘Have a blessed day.’ This can make you feel like you’ve been sprayed against your will with God cologne. ‘Get off me!’ I always want to scream. ‘Quick, before I start wearing ties with short-sleeved shirts!’ ” (Essay, “Your English is so good”)

Sedaris has written several plays with his sister, actress Amy Sedaris, under the name “The Talent Family.” Speaking and book tours have taken him around the world. He and Hugh Hamrick, who met in 1990 when Hamrick worked as a theatrical painter and set designer, have been in a relationship since then and as of this writing in 2024 live in West Sussex, England.

After California legalized same-sex marriage in 2008, Sedaris commented that he and Hamrick were “the sort of people who wouldn’t get married. And I know a lot of heterosexual couples who are the same way.” He then mused about a possible exception: “I would get married so I would never have to hear the word partner again. I like the word boyfriend, but now people feel like they have to say partner to be correct, and I think no, no, no, he’s my boyfriend. It wouldn’t matter if I were 80, he’d still be my boyfriend. If we got married, I suppose he’d be my husband, but anything beats partner.” (Newsweek, May 29, 2008)

Sedaris was among about 100 comedians invited to meet Pope Francis in June 2024 to help the pontiff explore how the “art of comedy can contribute to a more empathetic and supportive world.” He told this joke at a formal dinner the night before the papal audience: “A cop stops a car two priests are riding in. ‘I’m looking for a couple of child molesters,’ he tells them. The priests look at each other. ‘We’ll do it!’ they say.

“Substitute rabbis or Baptist ministers for priests, and you’ll get nothing. I mean, the Catholic Church earned those laughs, and every time its senior clerics look away, or quietly send an offending clergyman to the back bench, it’s making this scandal larger than its ministry, at least to an outsider such as myself.” (The New Yorker, Sept. 2, 2024)

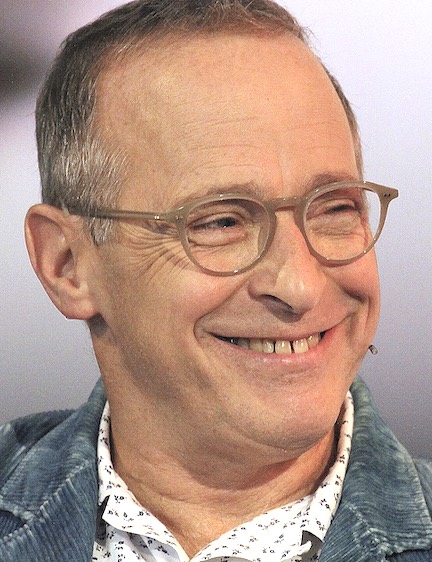

PHOTO: David Sedaris at the Frankfurt Book Fair in 2018; Heike Huslage-Koch photo under CC. 4.0.

“If I don’t see the Pope as dazzling, I suppose it’s because I’m not religious in any way. On my deathbed, I’ll likely cover my bases and beg for forgiveness, but not until I’m coughing up blood, or see Hugh reaching for the plug of my respirator. Does that make me an agnostic or a flat-out atheist?”

— "The Hem of His Garment," The New Yorker (Sept. 2, 2024)