April 9

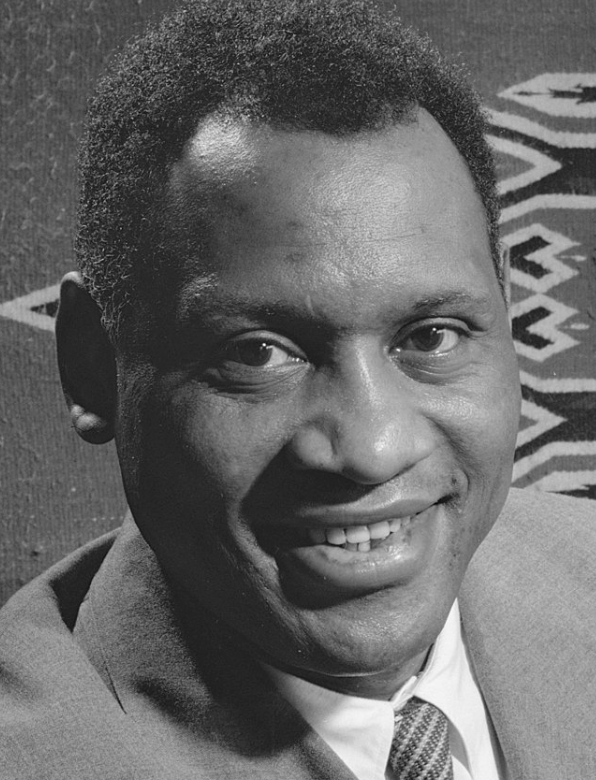

Paul Robeson

On this date in 1898, Paul Leroy Robeson, was born in Princeton, N.J., to Maria (Bustill) and William Robeson. His mother’s family was Quaker and his father, who escaped slavery as a teen, was a Presbyterian minister. Robeson was awarded a four-year scholarship to Rutgers, becoming that university’s third black student. He was a 12-letter athlete, Phi Beta Kappa scholar, Cap & Skull Honor Society member and valedictorian of his 1919 graduating class.

Robeson earned a law degree from Columbia in 1923 but encountered racial barriers, such as a white secretary refusing to take dictation from him. He turned to theater, starring in Eugene O’Neill’s “All God’s Chillun Got Wings” (1924) and “Emperor Jones.” Robeson changed the words to Jerome Kern’s song] “Ol’ Man River” when he starred in “Showboat.” It became the mellifluous singer’s signature song. He married Eslanda Goode (1921-65) and they had a son, Paul Jr..

He made 11 films and gave popular concert tours around the world but faced constant “Jim Crow” racism even in Europe. The increasingly radical Robeson, questioning why American blacks should be loyal to a country that denied them equal rights, was called before the House Committee on Un-American Activities in 1947 and was denied a passport until 1958. He spent time in Russia and abroad before returning to the U.S.

According to Warren Allen Smith in Who’s Who in Hell, Robeson was a nontheist. (D. 1976)

“A polyglot (10 languages, from Chinese to Swahili), he spoke out against man’s inhumanity to man and utilized naturalistic rather than supernaturalistic terms in arguing his outlook.”

— Warren Allen Smith, "Who's Who in Hell" (2000)

Charles Baudelaire

On this date in 1821, influential poet Charles Pierre Baudelaire was born in Paris into an aristocratic, Catholic family. His father, a former priest, had, at age 60, married a 26-year-old woman. After Charles’ father died, his mother remarried, leading to an estrangement and what he recalled as a feeling of “eternal solitude” during his childhood. He abandoned religious notions in his youth. Educated at College de Lyon and Lycee Louis le Grand, he entered law school, where he apparently acquired both syphilis and an opium habit but no law degree.

Baudelaire was described as being “on the barricades” of the revolution of 1848. He translated Edgar Allan Poe’s Tales in 1856. His own collection of 151 short poems, Les Fleurs du Mal (The Flowers of Evil) came out in 1857, including the poem “Les litanies de Satan.” He, the publisher and the printer were all prosecuted for obscenity and blasphemy and found guilty. Six poems were excised to conform to the laws. He had several mistresses, primarily Jeanne Duval, a woman of mixed race whom he immortalized in his poem “Black Venus.”

Along with Mallarme and Verlaine, Baudelaire was one of the so-called “Decadents.” He had some success as a critic, and knew many writers and painters. His life ended in a medical downward spiral, but not before penning “Pauvre Belgique,” a collection of insults toward that country, where he had lived as an invalid, which has been published in several editions. Baudelaire died in his mother’s arms. (D. 1867)

“God is the only being who does not have to exist in order to reign.”

— Baudelaire, quoted in "Who's Who in Hell" by Warren Allen Smith (2000)

Tom Lehrer

On this date in 1928, satiric songwriter Thomas Andrew Lehrer was born to a secular Jewish family in New York City. A precocious student, he earned a degree in math from Harvard at 18 and a master’s the following year. Lehrer recorded “The Songs of Tom Lehrer” in 1953, followed by “An Evening (Wasted) With Tom Lehrer.” He performed on stage reluctantly, finally bowing out altogether.

After writing for NBC’s “That Was The Week That Was” (1964), Lehrer cut his third and most political album, “That Was The Year That Was.” A musical revue of his work, “Tomfoolery,” later opened in London. Lehrer has taught at MIT, Harvard, Wellesley and at the University of California-Santa Cruz.

One of his most famous quips: “Political satire became obsolete when Henry Kissinger was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize.” His claim to fame in the freethought community is the perennial favorite “The Vatican Rag” (lyrics below). Lehrer has said: “I firmly believe all religion is bullshit, but I don’t think I would have gone and written a song expressing that, unless I could figure out a way to make it funny.” (Telephone interview with Jeremy Mazner, Nov. 21, 1995)

He died at age 97 at his home in Cambridge, Mass. (D. 2025)

PHOTO: Lehrer at about age 30.

First you get down on your knees,

Fiddle with your rosaries,

Bow your head with great respect,

And genuflect, genuflect, genuflect!Do whatever steps you want, if

You have cleared them with the Pontiff.

Everybody say his own

Kyrie eleison,

Doin’ the Vatican Rag.Get in line in that processional,

Step into that small confessional,

There, the guy who’s got religion’ll

Tell you if your sin’s original.

If it is, try playin’ it safer,

Drink the wine and chew the wafer,

Two, four, six, eight,

Time to transubstantiate!So get down upon your knees,

Fiddle with your rosaries,

Bow your head with great respect,

And genuflect, genuflect, genuflect!Make a cross on your abdomen,

When in Rome do like a Roman,

Ave Maria,

Gee it’s good to see ya,

Gettin’ ecstatic an’

Sorta dramatic an’

Doin’ the Vatican Rag!— "The Vatican Rag," words and music by Tom Lehrer (1965)

Paul Krassner

On this date in 1932, comedian and radical editor Paul Krassner was born in Brooklyn, N.Y., to Jewish parents. A violin prodigy, he performed at Carnegie Hall at age 6. He majored in journalism at Baruch College (then a branch of the City College of New York) and started performing as a comedian under the name Paul Maul. A co-founder of the Yippies (Youth International Party) with Abbie Hoffman and Jerry Rubin, he edited The Realist from 1958-74.

When People magazine dubbed the stand-up satirist the “father of the underground press,” he quipped that he would demand a paternity test. Both journalist and activist, Krassner, after interviewing a doctor who was performing abortions before their legalization, decided to run an underground abortion referral service.

An FBI agent once wrote a letter to the editor saying, “To classify Krassner as a social rebel is far too cute. He’s a nut, a raving, unconfined nut.” His 1993 memoir was subsequently titled Confessions of a Raving, Unconfined Nut: Misadventures in the Counterculture.”

Krassner edited Lenny Bruce’s biography, How to Talk Dirty and Influence People. His comedy records included “We Have Ways of Making You Laugh.” After ABC’s Harry Reasoner said, “Krassner not only attacks establishment values; he attacks indecency in general,” he called his one-man show “Attacking Indecency in General.” He wrote for Rolling Stone, Spin, Mother Jones, The Nation and Ron Reagan’s late-night talk show. Krassner was inducted in the Counterculture Hall of Fame in 2002.

His many books included The Winner of the Slow Bicycle Race: The Satiric Writings of Paul Krassner, Impolite Interviews, Murder at the Conspiracy Convention and Other American Absurdities. The San Francisco Examiner said of him: “He has lived on the edge so long he gets his mail delivered there.” Krassner repeatedly identified himself as an atheist in his interviews and writings.

He suffered for several years from a neurological disease and died at his home at age 87 in Desert Hot Springs, Calif. (D. 2019)

“I had become an atheist at the age of thirteen, when atomic bombs were dropped on Japan.”

— Krassner, "Confessions of a Raving, Unconfined Nut" (1993)

Hugh Hefner

On this date in 1926, Playboy mogul Hugh Marston Hefner was born in Chicago, the firstborn of Grace and Glenn Hefner’s two sons. His parents were strict Methodists. He went to school in the city and started a school newspaper at Steinmetz High School. He served in the U.S. Army during World War II. After discharge in 1946, he studied at the Chicago Art Institute for two years and then at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, completing a degree in psychology in 1950.

After college he began working as a promotional copywriter at Esquire in Chicago, which was then the premier men’s magazine. After three years he left in frustration, determined to start his own publication. With $8,000 from 45 investors, Hefner started Playboy magazine. The first issue was published in December 1953. It was an instant success, selling 50,000 copies. By 1959 Playboy was selling almost a million copies a month and Hefner was expanding his success. Playboy Enterprises established private key clubs, staffed with the iconic “bunnies” as hostesses, high-end resorts and modeling agencies. There were books and films and two television series. By 1970 the publication was selling 7 million copies a month.

After suffering a minor stroke in 1985, Hefner largely stepped back from Playboy Enterprises, leaving his daughter, Christie Hefner, at the helm. He instead focused on philanthropic efforts, making a few notable TV and film appearances to continue promoting the Playboy brand. He championed the issues of free speech and freedom of the press. He established the Playboy Foundation in 1965 to provide grants to nonprofits fighting censorship or researching human sexuality. The foundation also sponsors the Freedom of Expression Award, which is given at Sundance Film Festival every year.

While Playboy became a byword for objectification of women, with Gloria Steinem writing a famed piece, “A Bunny’s Tale,” for Show magazine on May 1, 1963, exposing what it was like to be a “Bunny,” Hefner placated some feminist critics by defending women’s reproductive rights. The A&E network’s 12-part miniseries titled “Secrets of Playboy” started airing in early 2022. Directed by Alexandra Dean, it reexamined Hefner and Playboy Enterprises through the lens of 2022 and in the wake of #MeToo. Dozens of women appear in the documentary to allege decades of sexual predation, including rape, and extensive use of illegal drugs and secret recordings inside the Playboy Mansion in the Holmby Hills neighborhood of Los Angeles.

In response, an open letter signed by about 500 people defended Hefner, calling the allegations unfounded: “From all we know of Hef, he was a person of upstanding character, exceptional kindness, and dedication to free thought.” In a statement, the company said “today’s Playboy is not Hugh Hefner’s Playboy. We trust and validate these women and their stories and we strongly support those individuals who have come forward to share their experiences.”

Alexandra Dean: “His progressive reputation was like a shield that stopped a lot of these allegations from touching him. It was just too hard to believe that this guy who was always promoting women at his company and was a progressive champion, how could he secretly be attacking women behind closed doors?” (Variety, Feb. 7, 2022) “That other side of Hugh Hefner really does need to have a reckoning now — we need to figure out how to reconcile the two Hugh Hefners and now decide what his real legacy is.”

Hefner married three times: to Mildred Williams (1949), Kimberley Conrad (1989) and Crystal Harris (2012). He also lived with a succession of younger “partners” at the mansion. He was 86 when he married Harris, a 26-year-old former Playmate. He had a son and a daughter with Williams and two sons with Conrad. He died at the mansion at age 91 of cardiac arrest and was interred in a mausoleum drawer next to Marilyn Monroe in Westwood Memorial Park. (D. 2017)

PHOTO: Hefner in 2010; Glenn Francis photo under CC 3.0.

“It’s perfectly clear to me that religion is a myth. It’s something we have invented to explain the inexplicable.”

— Hefner interview in Playboy (January 2000)

Sam Harris

On this date in 1967, author and neuroscientist Samuel Benjamin Harris, a key figure in the 21st century freethought movement, was born in Los Angeles, the son of TV producer and writer Susan (Spivak) Harris and actor Berkeley Harris, who divorced when Sam was 2. He grew up in his mother’s secular household and enrolled at Stanford University to study philosophy but left during his sophomore year to study Eastern religions and meditation in India. He eventually returned to Stanford and graduated in 2000.

He started writing his first book, The End of Faith, after the Sept. 11 attacks in 2001. It received the PEN/Martha Albrand Award for First Nonfiction in 2005 and was followed by his Letter to a Christian Nation in 2006. Harris married in 2004 and has two daughters with his wife Annaka, an author and science editor. They co-founded the nonprofit Project Reason in 2007. He received a Ph.D. in cognitive neuroscience in 2009 from UCLA. Five of his books are New York Times bestsellers. His latest, as of this writing, are Waking Up: A Guide to Spirituality Without Religion (2014) and Islam and the Future of Tolerance (with British activist Maajid Nawaz, 2015).

Harris is generally considered a member of the “Four Horsemen of New Atheism” along with Richard Dawkins and the late Daniel Dennett and Christopher Hitchens. The name comes from the title of a video they made during a two-hour unmoderated discussion at Hitchens’ home on Sept. 30, 2007. Journalist Simon Hooper described New Atheism as “the view that superstition, religion and irrationalism should not simply be tolerated but should be countered, criticized and exposed by rational argument wherever its influence arises in government, education and politics.”

Harris has no use for the term New Atheism or for the atheist label. In a 2007 speech he said that while he had become “one of the public voices of atheism, I never thought of myself as an atheist before being inducted to speak as one. I didn’t even use the term in The End of Faith, which remains my most substantial criticism of religion. And, as I argued briefly in Letter to a Christian Nation, I think that ‘atheist’ is a term that we do not need, in the same way that we don’t need a word for someone who rejects astrology. We simply do not call people ‘non-astrologers.’ All we need are words like ‘reason’ and ‘evidence’ and ‘common sense’ and ‘bullshit’ to put astrologers in their place, and so it could be with religion.”

PHOTO: By Christopher Michel under CC 4.0.

“It is time that we admitted that faith is nothing more than the license religious people give one another to keep believing when reasons fail.”

— Harris in "Letter to a Christian Nation" (Knopf, 2006)