On this date in 1941, Stokely Standiford Churchill Carmichael, aka Kwame Ture, was born in Port of Spain, Trinidad and Tobago, to Mabel “May” and Adolphus Carmichael, respectively a steamship stewardess and a carpenter and cab driver. His parents moved to New York when he was 2 and he was raised by his grandparents before joining his parents in Harlem at age 11. They attended a United Methodist church.

His time at the Bronx High School of Science “led Carmichael to sever his traditional religious notions and pushed him toward secular humanism,” wrote Christopher Cameron in Black Freethinkers: A History of African American Secularism (2019). Impetus came from “the curriculum at Bronx Science, which Carmichael stated was ‘heavily focused on Western rationalism, scientific materialism, and the scientific method, all of which I found logical and thus intellectually satisfying.’ Because of this curriculum, Carmichael claimed, ‘my religious feelings gradually lessened.’ ”

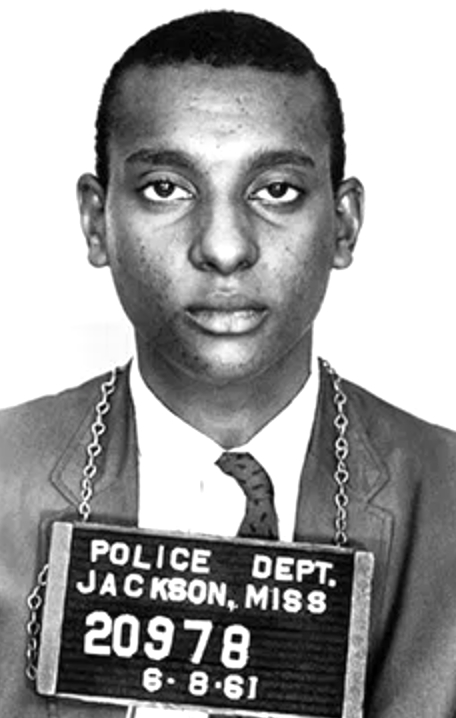

After graduating in 1960, he enrolled at Howard University in Washington, D.C., where he joined a chapter of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) and became active in the civil rights movement. In 1961 he went to Mississippi along with other Freedom Riders, was arrested and served 49 days behind bars in the notorious Parchman Farm prison.

Despite attending Young Communist League meetings, he never joined, according to Cameron: “His own devotion to religion was waning, but he knew that was not the case for most black people in the United States, and he [wrote in Ready for Revolution that he] ‘did not want to be alienated from my people because of Marxist atheism.’ … Carmichael came to believe that if he was going to be a serious civil rights activist, ‘then any talk of atheism and the rejection of God just wasn’t going to cut it.’ ”

He continued his activism, succeeded John Lewis as SNCC chairman in 1966 and gave his first “black power” speech at a March Against Fear rally organized by James Meredith. After stepping down as SNCC chair, he wrote the book Black Power: The Politics of Liberation (1967) with Charles Hamilton. He started distancing himself from the Black Panther Party after serving for a time as its “honorary prime minister.”

In 1968, now calling himself Kwame Ture, he married the South African singer Miriam Makeba and they settled in Conakry, Guinea, in west Africa. Makeba was named Guinea’s delegate to the United Nations. After divorcing in 1973, he married Marlyatou Barry, a Guinean doctor. They had a son, Bokar (b. 1982) before divorcing.

In a long essay in Life magazine in 1967, photojournalist and filmmaker Gordon Parks wrote how Carmichael’s mother once confronted him about the danger of his activism by saying, “I’ve got one son. Let other Negroes give of theirs for a while.” He answered, “What’s all this religious stuff you taught me about Abraham sacrificing his son. If you really believe that, you shouldn’t mind sacrificing your own son.”

In his last years, Carmichael promoted the All-African People’s Revolutionary Party founded by Ghanaian politician Kwame Nkrumah to unify the continent politically. He often returned to speak at Howard University and other U.S. campuses. After a 1996 prostate cancer diagnosis, he was treated in Cuba and at Columbia-Presbyterian Medical Center in New York before returning to Guinea.

He died of cancer at age 57 in Conakry. Julian Bond, NAACP chair, said Carmichael “ought to be remembered for having spent almost every moment of his adult life trying to advance the cause of black liberation.” (D. 1998)