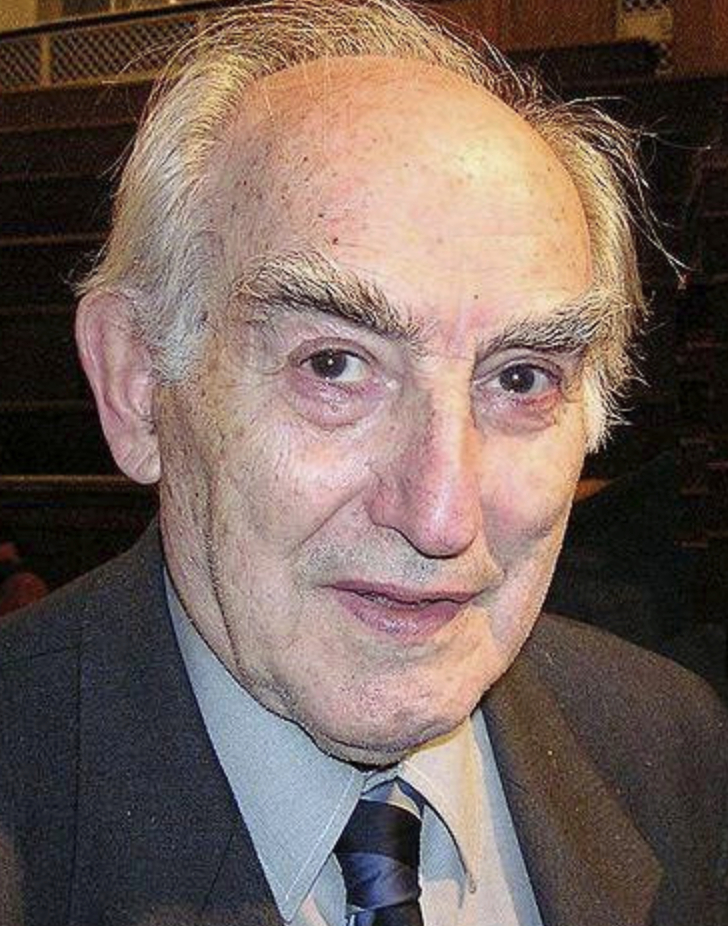

Born on this date in 1916 (Sept. 21 on the old Russian calendar) was Vitaly Lazarevich Ginzburg, a Nobel Prize-winning physicist and a father of the Soviet hydrogen bomb.

Ginzburg’s obituary in the UK Guardian called him a “vehement atheist” who strongly opposed the role of the Russian Orthodox Church in state affairs after the 1991 Soviet collapse: “He protested against attempts to introduce religious lessons in schools, telling a newspaper in 2007 that ‘these Orthodox scoundrels want to lure away children’s souls.’ As a result, several Orthodox Christian groups threatened to sue him for ‘offending millions of Russian Christians.’ “

Ginzburg was born in Moscow to Jewish parents. His father was an engineer and his mother, who died of typhoid when he was 4, was a physician. After working as an assistant in an X-ray lab, he earned a Ph.D. in physics from Moscow State University and joined the Lebedev Institute. He and his first wife, Olga Zamsha, were married in 1937 and divorced in 1946, when he married Nina Ermakova. In 1944 Nina had been arrested for allegedly being part of a plot to kill Stalin. She was released in 1945 but was exiled to Gorki, where Ginzburg met her. The institute had been moved to Gorki during World War II.

His areas of expertise in physics included quantum theory, astrophysics and radioastronomy. Ginzburg was originally turned down to be part of the Soviet hydrogen bomb program due to his wife’s exile and his Jewish background, but later he joined a team that included Andrei Sakharov. Sakharov suggested using alternating layers of uranium and fuel in the bomb. Ginzburg suggested using lithium-6 as fuel because, when hit by neutrons, it would release tritium and helium nuclei and significant amounts of energy. He would later say that only his participation in the H-bomb project saved him from the firing squad.

Ginzburg next turned his attention to superconductivity, the ability of some materials to carry electricity without any losses due to friction. With physicist Lev Landau, he worked out equations that correctly predicted a superconductor’s tolerance for a magnetic field. Their work paved the way for Alexei Abrikosov to develop ways to achieve superconductivity despite the presence of high magnetic fields. Ginzburg and Abrikosov shared the 2003 Nobel Prize in physics with Anthony Leggett.

Ginzburg was part of a group of scientists who helped discredit Trofim Lysenko’s hypothesis that acquired physical characteristics could be inherited, a belief that impeded genetic research in Russia for decades.

Commenting when he was 86 on Karl Marx‘s aphorism that “Religion is the opium of the people,” Ginzburg said, “I am not a supporter of Marxism, but I fully agree with this formulation.” (“Notes on Jewish History,” Dec. 26, 2002) He said he envied believers, “But the mind is given to man in order to control his emotions and not engage in self-deception, belief in miracles.”

He died of cardiac arrest at age 93. (D. 2009)