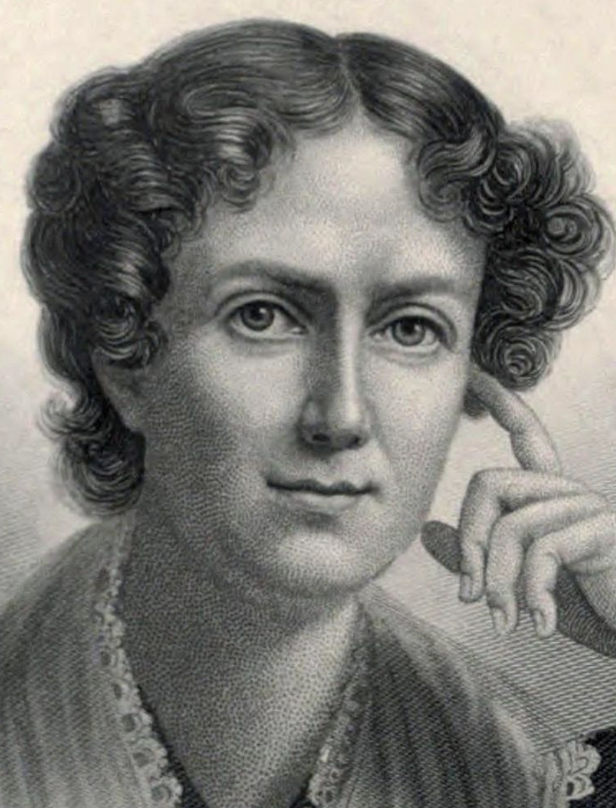

On this date in 1795, Frances Wright, the first woman to publicly lecture in the United States, was born an heiress in Scotland. An arresting five feet, 10 inches as an adult, Wright influenced fashion of her day with her liberating style of ringlets and later her adoption of “Turkish trousers.” She traveled with her younger sister Camilla to America in 1818. Her play, “Altorf,” was staged to acclaim in New York in 1819, where she shocked society by using her byline as a female author.

Her travel book, Views of Society & Manners in America (1820), caused a sensation in Great Britain and abroad. Freethinker Jeremy Bentham became her mentor and General Lafayette her confidante. Returning at 29 to America, Frances became a U.S. citizen. As an early and passionate abolitionist, she began a noble but ill-fated model communal plantation to educate slaves for freedom at Nashoba, Tenn. They would have no religion but “kind feeling and kind action,” Wright decreed. The experiment unraveled for lack of money.

At 33, Wright launched her speaking career on July 4, 1828, in Cincinnati, seeking to “destroy the slavery of the mind” and counteract the effects of a religious revival on women, as well as the Christian Party in Politics movement. Wright called for the education of women and the rejection of religion. Her historic speaking tour won her adoration from progressives such as the young Walt Whitman, who recalled how “we all loved her: fell down about her.” But press and clergy dubbed Wright “The Red Harlot of Infidelity” and a “voluptuous preacher of licentiousness.”

Wright urged, “Turn your churches into halls of science, exchange your teachers of faith for expounders of nature. … Fill the vacuum of your mind!” Practicing what she preached, she purchased an old church in New York City for $7,000 and renamed it the “Hall of Science.” It opened its doors in April 1829 for lectures, a radical bookstore and at one time offered a health clinic. She and Robert Dale Owen launched The Free Enquirer and the Working Men’s Party, advocating a 10-hour workday, for which she was dubbed a “female Tom Paine” by the mayor of New York.

After an unsuccessful marriage to Frenchman Phiquepal D’Arusmont, resulting in the birth of a daughter, Wright returned to the U.S., where she lectured and wrote. When Wright divorced her husband, she tragically lost custody of her daughter. She broke her hip in a fall and died prematurely after great suffering in Cincinnati. D. 1852.