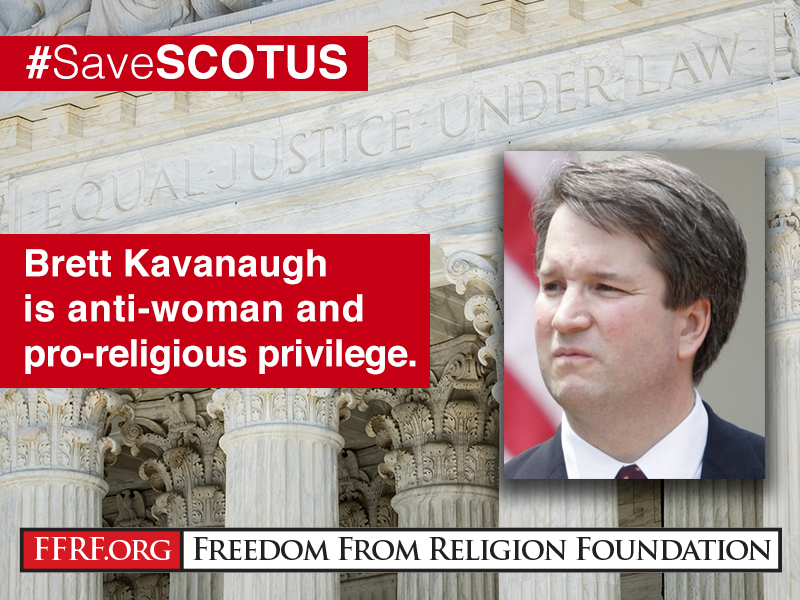

The Freedom From Religion Foundation says President Trump’s new Supreme Court nominee Judge Brett Kavanaugh would be “a disaster for the constitutional principle of separation between state and church” and tilt the court to the religious right for more than a generation.

FFRF is asking its nationwide membership of over 32,000 secularists to call their senators to strongly oppose this nominee and hold confirmation hearings in the next session of Congress. Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell, who will be in charge of the confirmation, himself said, “The American people should have a voice in the selection of their next Supreme Court Justice.” This has become known as the “McConnell Rule.” McConnell has already stated that he intends to violate the eponymous rule for Kavanaugh and, indeed, McConnell recommended Kavanaugh to the president.

“If Kavanaugh is confirmed, he will unquestionably eviscerate the Establishment Clause of the First Amendment,” warn FFRF Executive Directors Dan Barker and Annie Laurie Gaylor. “It seems unlikely the cherished wall of separation between state and church protecting true religious liberty could survive intact. Many of our hard-won freedoms would be gutted.”

Crucially, Kavanaugh would replace Justice Anthony Kennedy — a nominal swing vote who was often disappointing, but his swing vote nevertheless upheld LGBTQ rights and abortion rights.

FFRF noted that the 53-year-old Catholic, a former clerk for Kennedy, would be a threat for a host of important progressive and humanist issues. Kavanaugh, who currently serves on the U.S. Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia, has seemingly never met a regulation he wouldn’t strike down, including regulations to prevent another financial collapse as in 2008, to protect clean air, clean water, and fight climate change, to enforce safety standards for the auto industry, uphold the Affordable Care Act and protect workers.

Of most relevance to the work of FFRF, a state/church watchdog, is Kavanaugh’s disturbing history of working to privilege religion, harm women’s rights and tear down the wall separating state and church.

Two recent decisions illustrate his views, revealing that Kavanaugh seems “less driven by the law than by ideology,” notes FFRF Director of Strategic Response Andrew L. Seidel, who with FFRF’s Strategic Response Team researched his record.

Kavanaugh dissented in a 2017 case garnering national attention and concern, involving a pregnant, unaccompanied minor immigrant under detention, whom the Trump administration was preventing from exercising her right to end an unwanted pregnancy. Kavanaugh wrote that forcing the 17-year-old girl to continue her pregnancy for so many weeks she risked being unable to obtain an abortion was not an “undue burden.” Conversely, in a 2015 case, Priests for Life v. HHS, he wrote a dissenting opinion calling it a “substantial burden” on religion for a religious organization wanting to opt out of the contraceptive mandate to be asked simply to fill out a five-blank form — name, corporate name, date, address, sign.

“In Kavanaugh’s legal world, it burdens religion to fill out five blanks on a form, but it’s not a burden to force a teenager to carry a unwanted pregnancy. That is alarming,” adds Seidel.

Kavanaugh evinces hostility to state-church separation.

Kavanaugh’s record shows a consistent hostility to state-church separation. Even while working in private practice he submitted amicus briefs on a number of cases involving the Establishment Clause, always on the wrong side.

In the landmark 2000 case, Santa Fe Independent School District v. Doe, the last big school prayer case decided by the high court, it ruled unconstitutional prayers delivered over the school public address system at school-scheduled, school-sponsored events, including student led.

Kavanaugh wrote an amicus brief defending the imposition of prayers upon students on behalf of U.S. Rep. Steve Largent, a former football player. Throughout the brief, Kavanaugh argued that the case was about “banning” students’ religious speech. It was really about a public school (with its own tradition of imposing prayer) handing religious students a government-owned megaphone to impose the prayers on other students at public school events. That distinction is crucial, and Kavanaugh’s inability to grasp it is disturbing.

Kavanaugh uses inflated language to disparage advocates of state-church separation — in other words, those of us who support the First Amendment — as “absolutist[s],” “hostile to religion in any form,” advocating for an “Orwellian world,” and seeking “the full extermination of private religious speech from the public schools” and “to cleanse public schools throughout the country of private religious speech.”

In an astonishing paragraph, he portrays Christians as beleaguered and downtrodden folks “below socialists and Nazis and Klan members and panhandlers and ideological and political advocacy groups of all stripes,” rather than the privileged majority they are.

In one of the most concerning passages in the brief, Kavanaugh sends a clear signal that he does not think the Supreme Court should even apply legal tests to the Establishment Clause. In other words, it appears he would happily overrule the critical rule of law laid out in Lemon v. Kurtzman (1971), known as “The Lemon Test.” The Lemon Test simply says a government action violates the Establishment Clause if it (1) doesn’t have a secular purpose; or (2) has the primary effect of advancing or inhibiting religion, or (3) fosters excessive entanglement between religion and government. Kavanaugh wrote: “In Establishment Clause cases, the search for an overarching test is not always necessary, and can sometimes be counterproductive or even harmful.”

Kavanaugh continued to display hostility to state-church separation when he became a judge on the Court of Appeals for the D.C. Circuit.

The D.C. Circuit dismissed a case taken by atheist Michael Newdow challenging the addition of “so help me God” to the presidential oath and inaugural prayers. Notably, religious language is not present in the oath laid out in Article II of our secular Constitution, yet it is typically added by the chief justice during inaugurations.

When the court threw out the case on procedural grounds, Kavanaugh wrote separately to say that the challengers (who included FFRF) should have lost on the merits “because those long-standing practices do not violate the Establishment Clause.” Essentially, Kavanaugh relied on a long history of use of the words “so help me God,” supposedly, he wrote, dating back to George Washington. But Washington never uttered those words. The history of “so help me God,” is considerably shorter. The phrase has only been in regular use since World War I. In any event, that a constitutional violation is longstanding does not make it any less a violation. The argument from tradition is a poor argument which concedes that there is no better reason to continue the practice, and it is disconcerting that Kavanaugh would have relied on it to uphold violations of the First Amendment.

In two cases, Kavanaugh has sided with the U.S. Navy chaplaincy and against plaintiffs alleging various forms of discrimination, including actions that favored Catholics against other chaplains. In re Navy Chaplaincy, 534 F.3d 756 (D.C. Cir. 2008); In re Navy Chaplaincy, 738 F.3d 425 (D.C. Cir. 2013).

Kavanaugh defended Florida’s unconstitutional school voucher scheme.

Kavanaugh represented pro-voucher Florida Gov. Jeb Bush in a constitutional challenge to Florida’s school voucher legislation. Florida plaintiffs — including a branch of the NAACP, the Florida Education Association, and the AFL-CIO — sued Bush and the Florida Department of Education over the allocation of public funds to private schools through a voucher system. The Florida Supreme Court held the voucher system Kavanaugh defended was unconstitutional.

He went back to Florida to help Bush litigate the outcome of Florida’s electoral votes in the disputed Bush-Gore 2000 presidential election. More successful there than with the vouchers, Kavanaugh then went to work in the George W. Bush White House as associate counsel to the president. Bush nominated him to the U.S. Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia in 2003, and after a bitter fight that lasted three years, he finally was seated in 2006.

Would Kavanaugh hold the president accountable for wrongdoing?

While still in private practice, Kavanaugh was a key member of Kenneth Starr’s team investigating President Clinton and was a prominent voice calling for Clinton’s impeachment. But in a turn that seems hypocritical, he has lately written that presidents are under such extraordinary pressure they “should be excused from some of the burdens of ordinary citizenship while serving in office.” This statement was likely received well by Trump, facing a dogged and productive investigation by special counsel Robert Mueller.

Kavanaugh would be yet another Catholic on the already heavily Catholic Court.

The Constitution prohibits religious tests for public office, but one would think there was a requirement that Catholics hold a majority on the Supreme Court. Currently, although Catholics are about 20 percent of the overall population, five of the nine justices are Catholic, including outgoing Kennedy. The Kavanaugh nomination would retain the lopsided Catholic majority, and be a lost chance for more diversity (such as a nonreligious justice or even another Protestant!).

The National Review endorsed Kavanaugh partly because of this zealous Catholicism: “He is a lector at his parish, and he volunteers with Catholic charities, teaches and mentors in Catholic (and other) schools, and coaches his daughters’ Catholic Youth Organization (CYO) basketball teams.”

FFRF is committed to fighting any nominee that is so clearly hostile to American secularism.

“This is the legal fight of the century for America. Our nation’s future, our constitution and our civil rights hang in the balance,” says Gaylor.