June 5

Adam Smith

On this date in 1723, Adam Smith was born in Scotland. He was educated at Glasgow University, where he won an exhibition giving him a scholarship to Oxford on the condition that he become a minister of the Church of Scotland. A rationalist, he ignored the condition. Smith became chair of logic, then moral philosophy, at Glasgow University, where he sought unsuccessfully to discontinue classroom prayers and religious duties. He served as dean of the faculty from 1760-62, when he became vice rector.

He was on friendly terms with Glasgow’s elite freethinkers, including David Hume and deistic engineer James Watt. Smith’s Theory of the Moral Sentiment was published in 1759. As tutor to the young Duke of Buccleuch, he lived in France for a while, where he became friendly with Voltaire, Rousseau and the French Encyclopedists. In 1767 he joined the Royal Society. His master work, Inquiry into the Nature and Causes of the Wealth of Nations, was published in two volumes in 1776. The classic explanation of the free market was quickly translated into many other languages. In 1777, Smith’s Life of Hume came out, clearly endorsing Hume’s rationalist views.

After Smith became Lord Rector of Glasgow University in 1787, a position requiring that he bow to convention, he begged off aiding in the posthumous publication of Hume’s Dialogues on Natural Religion. Smith was said to have burned 16 volumes of his own manuscripts before his death. He advised, “Virtue is more to be feared than vice, because its excesses are not subject to the regulation of conscience.” During his lifetime, Smith made many anonymous acts of charity. D. 1790.

“Science is the great antidote to the poison of enthusiasm and superstition.”

— Smith, "The Wealth of Nations" (1776)

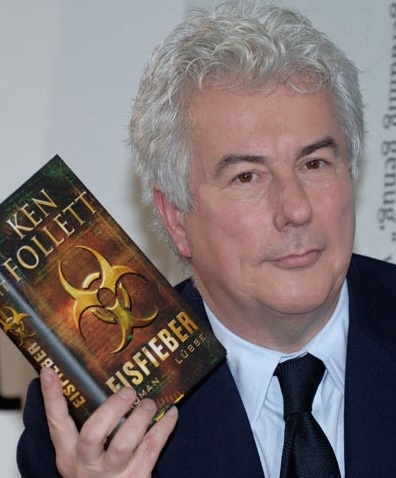

Ken Follett

On this date in 1949, prolific author Kenneth Martin Follett was born in Cardiff, Wales, the eldest of four children of Martin and Lavinia Follett, respectively a tax inspector and stay-at-home mother. Follett’s parents and extended family belonged to a Puritan religious group called the Plymouth Brethren. “For us, a church was a bare room with rows of chairs around a central table. Paintings, statues and all forms of decoration were banned,” he remembers.

He was not allowed to watch TV or go to movies, so he found entertainment in books. When he was 10 the family moved to London, where he attended public schools, graduating with honors in philosophy in 1970 from University College. Follett then worked as a reporter with the South Wales Echo and London Evening News and started writing novels in his spare time.

He and Mary Elson had wed in 1968, the same year their son Emanuele was born. Daughter Marie-Claire was born in 1973. His spy novel Eye of the Needle (1978) became a best-seller, as did four others in that genre which were popular with readers in several languages. By then Follett was deputy managing director at Everest Books in London. The Pillars of the Earth (1989), a historical novel about building a cathedral in an English village in the Middle Ages, got rave reviews.

The Times of London once asked readers to rate the “60 greatest novels” of the last 60 years. Pillars placed second after To Kill a Mockingbird. Follett wrote in the preface: “What’s more, I don’t believe in God. I’m not what you would call a spiritual person. According to my agent, my greatest problem as a writer is that I’m not a tortured soul. The last thing anyone would have expected from me was a story about building a church.”

His historical Century Trilogy (2010-14), set in the 20th century, details the lives of five families: American, English, German, Russian and Welsh. His book sales top 130 million copies. He married politician Daphne Barbara Hubbard in 1985. She went on to serve 13 years in Parliament and in Prime Minister Gordon Brown’s administration. In 2010, Follett and 54 other public figures signed an open letter in The Guardian objecting to Pope Benedict XVI’s state visit to the UK.

Photo (cropped) by Blaues Sofa under CC 2.0.

“By the time I applied to college, I had grave doubts about my parents’ religion. I had arguments with my father about theology. Philosophy is, in part, a study of what is a good argument and what is not; what is evidence and what is fake evidence. So, my interest in philosophy stemmed from the agonizing conflict I had over whether or not I believed in my parents’ religion. In the end, I completely rejected it. I’m not a religious person. I’m an atheist. I ended up being the absolute opposite of my parents.”

— Huffington Post interview, Sept. 17, 2014