January 29

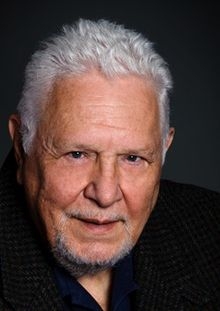

W.C. Fields

On this date in 1880, comedian W.C. Fields (né William Claude Dukenfield) was born in Philadelphia. His father was a Cockney immigrant and his mother a native Philadelphian. Fields dropped out after four years of schooling to work with his father, who ran a horse-drawn vegetable cart. A rough home life drove Fields away by the age of 11. He lived on the streets, was occasionally beaten up and sometimes jailed.

By 13 he had become skilled at juggling and playing pool. That year he moved to Atlantic City, where he was hired to juggle (perfecting the appearance of losing his juggling pieces) and, when business was slow, to pretend to drown for crowd amusement.

At 19 he was dubbed “The Distinguished Comedian.” By 23 he had played at Buckingham Palace in London, appearing the same evening as Sarah Bernhardt. Fields was on the program with Charles Chaplin and Maurice Chevalier at the Folies-Bergeres. Fittingly, his first movie, at age 35, was “Pool Sharks” (1915).

Fields appeared in 37 movies, including “David Copperfield” (despite his adage “Never work with animals or children”) and “My Little Chickadee” (1940). Known for his poses as a caustic curmudgeon and imbiber, Fields actually had two sons (one outside marriage who was raised by foster parents) and did not appear in public inebriated.

In 1945, crippled by arthritis and weakened by cirrhosis of the liver, he moved out of his Bel Air home into Las Encinas Sanitarium, where he died on Christmas Day 1946 of a gastric hemorrhage at age 66. His son and estranged wife contested a clause in his will leaving part of his estate to establish a “W. C. Fields College for Orphan White Boys and Girls, where no religion of any sort is to be preached.” (Man on the Flying Trapeze: The Life and Times of W.C. Fields by Simon Louvish, 1997.)

Actor Edgar Bergen, speaking at Fields’ memorial service in Forest Lawn, said: “Of the five hundred religions in the world he had his own, and he hoped his friends would understand his requests. It seems wrong not to pray for a man who gave such happiness to the world. But this is the way he wanted it.” (D. 1946)

PHOTO: Fields as Micawber in the 1935 film “David Copperfield.”

“[Fields] regarded all religions with the suspicion of a seasoned con man.”

— "W.C. Fields: A Biography" by James Curtis (2004)

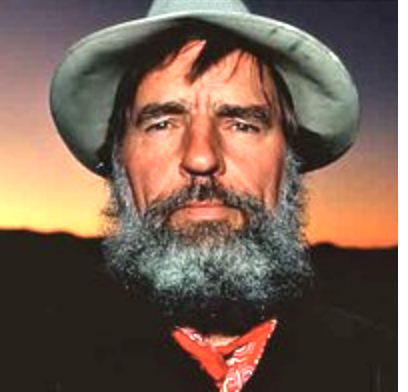

Victor Stenger

On this date in 1935, particle physicist, author and skeptic Victor John Stenger was born in Bayonne, New Jersey. Stenger, the son of a first-generation Lithuanian immigrant and a second-generation Hungarian immigrant, grew up in a Catholic neighborhood. He earned a bachelor’s in electrical engineering from Newark College of Engineering and a master’s in physics from UCLA, followed by a Ph.D. After taking a position on the University of Hawaii faculty, Stenger began a long and influential career during one of the most exciting times for physics in history.

His experiments helped establish standard models in physics, examining and uncovering the properties of quarks, gluons, neutrinos and “strange” particles. Stenger also made contributions to the emerging fields of high-energy gamma ray and neutrino astronomy. In his last major research endeavor before retiring in Colorado in 2000, Stenger collaborated on a project in Japan that demonstrated for the first time that the neutrino has mass. The project’s head researcher won the Nobel Prize in Physics in 2002.

In addition to his numerous and influential peer-reviewed articles, Stenger wrote 12 books, including the 2007 bestseller God: The Failed Hypothesis: How Science Shows that God Does Not Exist. Some of his other titles include Not By Design: The Origin of the Universe (1988), The Unconscious Quantum: Metaphysics in Modern Physics and Cosmology (1995), The New Atheism: Taking a Stand for Science and Reason (2009), The Fallacy of Fine-Tuning: Why the Universe Is Not Designed for Us (2011), and God and the Folly of Faith: The Fundamental Incompatibility of Religion and Science and Why It Matters (2012).

Stenger’s work hinged on the interplay between philosophy, particle physics, quantum mechanics and religion. He was a self-professed skeptic and atheist, maintaining that all things in existence — including consciousness and the subjective illusion of libertarian free will — may be revealed and described by rational scientific inquiry without resorting to supernatural explanations, the meaning of which are empty, useless, unproductive and put a crippling end to intellectual progress.

In order to champion these causes, Stenger pursued public speaking, debating prominent Christian apologists and participating in the 2008 “Origins Conference” hosted by the Skeptics Society. Stenger was a member of a number of skeptics and humanist organizations, including presidential stints with the Hawaiian Humanists from 1990-94 and the Colorado Citizens for Science from 2002-06.

He was an honorary director of FFRF, a member of the Society of Humanist Philosophers and the Free Inquiry editorial board, and a fellow of the Center for Inquiry and the Committee for Skeptical Inquiry. Among a number of visiting positions, Stenger was an adjunct professor of philosophy at the University of Colorado and an emeritus professor of physics at the University of Hawaii. Stenger lived with his wife Phylliss, whom he married in 1962. They had two children. (D. 2014)

PHOTO: Licensed under CC BY 3.0.

“Science flies you to the moon. Religion flies you into buildings.”

— Stenger, who suggested this slogan post-9/11 after ideas for bus signs were solicited by the Richard Dawkins Foundation.

Edward Paul Abbey

On this date in 1927, author Edward Paul Abbey was born in Indiana, Pa., to Mildred (Postlewait) and Paul Abbey, the eldest of five siblings. Both were hardworking, independent persons, and while Mildred was a lifelong liberal Presbyterian, Paul was more radical, declaring himself an atheist and a socialist as a young adult. Edward Abbey served in the U.S. Army as a military police officer in Italy and then enrolled at the University of New Mexico, where he earned a B.A. in philosophy and English in 1951 and a master’s in philosophy in 1956. He married Jean Schmechal, the first of his five wives (with whom he had five children), as an undergrad. He was removed as editor of the student newspaper for putting Diderot’s famous quote, “Man will never be free until the last king is strangled with the entrails of the last priest,” on the cover of one issue.

He worked as a welfare caseworker, teacher, bus driver and technical writer before starting a career as a ranger and fire lookout at several national parks or monuments. His two seasons at Arches National Monument (later a national park) near Moab, Utah, in 1956-57 provided the grist for the book that brought him acclaim, Desert Solitaire: A Season in the Wilderness (in 1968), a nonfiction work that was preceded by three novels. His 1975 comic novel The Monkey Wrench Gang, about a group of ecological saboteurs is perhaps his best-known work. While he wrote primarily about environmental issues and land-use policies, Abbey was basically a political anarchist, and according to Wilderness.net, “he wasn’t comfortable with environmental activists or activism as a whole.”

His best friend Jack Loeffler recorded Abbey’s thoughts on religion after their 1983 camping trip in the Superstition Mountains of Arizona, included in his 1989 book Headed Upstream: Conversations with Iconoclasts, in which Abbey said, “I regard the invention of monotheism and the otherworldly God as a great setback for human life.” Abbey himself roundly condemned religion in his own works, particularly in A Voice Crying in the Wilderness, published in 1989, the year he died of esophageal hemorrhaging after surgery for a congenital circulatory disorder. “What is the difference between the Lone Ranger and God?” Abbey asked, before answering, “There really is a Lone Ranger.”

“Whatever we cannot easily understand we call God; this saves much wear and tear on the brain tissues.”

— "A Voice Crying in the Wilderness: Notes from a Secret Journal" (1989)

Freethinkers Day

Freethinkers Day celebrates the life of Thomas Paine, born on today’s date in 1737 (see entry on this page). The day educates the public about Paine’s work and about freethinking, which rejects arbitrary authority and puts reason and logic before faith. The holiday started being observed in the 1990s by The Truth Seeker magazine founded by D.M. Bennett in New York in 1873 and still in publication. (October 12 is observed as Freethought Day to note the beginning of the end of the Salem witch trials.)

—

Thomas Paine

On this date in 1737, Thomas Paine was born in Thetford, Norfolk, England, emigrating to British colonial America in 1774. Paine wrote the pamphlet “Common Sense” in 1776, fanning the flames of the American Revolution. Paine is best known for his political writings. No better index to his character can be found than his reply to Ben Franklin’s remark, “Where liberty is, there is my country.” Paine replied, “Where liberty is not, there is mine.” Without the pen of Paine, said one contemporary, the sword of George Washington would have been wielded in vain.

A freethinker in the 18th-century mode of deism, although he never described himself as a deist, Paine wrote the classic criticism of the bible, The Age of Reason (1792), completing the second volume under arduous conditions of imprisonment in France. “I believe that religious duties consist in doing justice, loving mercy, and endeavoring to make our fellow creatures happy. I do not believe in the creed professed by the Jewish church, by the Roman church, by the Greek church, by the Turkish church, by the Protestant church, nor by any church that I know of. My own mind is my own church.”

He wrote that organized religion was “set up to terrify and enslave” and to “monopolize power and profit.” Paine repudiated the divine origin of Christianity on the grounds that it was too “absurd for belief, too impossible to convince and too inconsistent to practice.” He was vilified for his unabashed analysis of the bible when he returned to America in 1802. Even a century after his death, Theodore Roosevelt referred to Paine, the man who named the United States of America, as “a filthy little atheist,” ignoring the fact that Paine wrote in The Age of Reason, “I believe in one God, and no more; and I hope for happiness beyond this life.” In Rights of Man (1791) he wrote, “My country is the world, and my religion is to do good.”

Paine married Mary Lambert in 1759. She died in early labor a year later, along with the child. He married again in 1771 but legally separated three years later just before leaving for America. He died in New York City at age 72. (D. 1809)

“Whenever we read the obscene stories, the voluptuous debaucheries, the cruel and tortuous executions, the unrelenting vindictiveness, with which more than half the Bible is filled it would be more consistent that we call it the word of a demon than the word of God. It is a history of wickedness that has served to corrupt and brutalize.”

— Paine, "The Age of Reason" (1792)

Robin Morgan

On this date in 1941, Robin Morgan — feminist author, journalist, editor, lecturer, organizer, atheist and activist — was born in New York City. As she notes in her memoir, Saturday’s Child, “Saturday’s child has to work for a living.” She started at age 2 as a tot model. She had her own radio show by age 4, then acted in the role of Dagmar on the popular series “Mama” in the 1940s and 1950s. She left show biz to write and became a founder and leader of the contemporary feminist movement.

Morgan’s columns and articles for Ms. magazine appeared from 1974-88. She was editor-in-chief of Ms. for four years and later its international consulting editor. Her groundbreaking anthology Sisterhood Is Powerful came out in 1972, followed by Sisterhood Is Global (1984), Sisterhood Is Forever (2003) and Fighting Words: A Toolkit for Combating the Religious Right (2006). Morgan is a distinguished poet and the author of more than 20 books, including her 2006 novel The Burning Time, based on the first witchcraft trial in Ireland.

She has traveled the globe as a feminist activist, scholar, journalist and lecturer. She is a co-founder of the Feminist Women’s Health Network, the Feminist Writers’ Guild, Media Women and the National Network of Rape Crisis Centers. Her timely The Demon Lover: On the Sexuality of Terrorism tells the personal story of her travel to refugee camps in the Middle East, with a post-9/11 introduction and afterword. A recipient of many awards, she was named FFRF’s Freethought Heroine in 2005 and is an honorary director.

She was married from 1962-83 to poet Kenneth Pitchford, a founding member of the Effeminist movement. He and Morgan, who are both bisexual, have a son, musician Blake Morgan.

She was diagnosed with Parkinson’s in 2010. Instead of curtailing her effectiveness, the diagnosis inspired her to take the lead in creating the Parkinson’s Disease Foundation’s Women and PD Initiative to help women be better served by research, treatment and assistance for their caregivers. Morgan has shared her struggle with the disease by writing and presenting about her experiences at a variety of venues, including her 2015 Ted Talk, viewed over a million times. In 2018 she published Dark Matter: New Poems, which includes the verses from that presentation.

“Religion is not about awe and joy, despite its purported proprietorship of these and its promise to eventually deliver what already lies around us every day, freely available for utter celebration. Religion is about something else. The etymology of the word itself, from the Latin, to being ‘bound by rules.’ Religion is about terror.”

— Freethought Heroine acceptance speech at FFRF's national convention (Nov. 11, 2005)

Albert Gallatin

On this date in 1761, Albert Gallatin (né Abraham Alfonse Albert Gallatin) was born in Geneva, Switzerland. He studied mathematics, natural history and Latin at Geneva University, where he graduated with honors in 1779. Voltaire had been a friend of his grandmother and was an influence on Gallatin, also a deist. In 1780, to evade family pressure to join up with the Hessians, Gallatin gave up family and fortune to emigrate to America to demonstrate “a love for independence in the freest country of the universe.”

He taught French at Harvard, then moved to Virginia in 1785, where he was elected to the legislature. After being elected to the U.S. Senate, Gallatin was rejected by the body as a non-citizen, but returned to Congress in the House in 1795. He wrote “Views of the Public Debt, Receipts & Expenditures of the U.S.” in 1800, which is described by the U.S. Department of the Treasury website as “still a classic” analysis of the fiscal operations of government under the Constitution.

Jefferson believed the Alien and Sedition Act was framed to drive Gallatin — who worked to keep down expenses, especially for war and the military — from office. Jefferson offered Gallatin the position of secretary of state. He served under both Jefferson and Madison from 1801-13. He was minister to France from 1815-23, then served as an envoy to Great Britain. A lifelong scholar, he was a co-founder of New York University.

Determined to keep it secular, he later resigned from a position there when “a certain portion of the clergy had obtained control.” Gallatin opposed slavery and helped negotiate the Treaty of Ghent, ending the War of 1812. He served with the American Ethnological Society, helping to preserve native languages, and was president of the New York Historical Society. (D. 1849)

“[A] foundation free from the influence of clergy.”

— Gallatin's stated aim for New York University, cited by Joseph McCabe, "A Biographical Dictionary of Modern Rationalists" (1920)

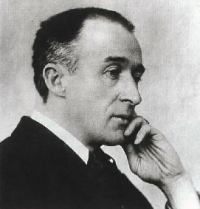

Frederick Delius

On this date in 1862, composer Fritz Theodor Albert Delius was born in England to parents who had emigrated from Germany and had 14 children. In 1884 he moved to Florida at his father’s behest to manage an orange plantation, staying for about 18 months. While there he became enchanted with African-American music, which would be documented in his “Florida Suite.” He studied at the Leipzig Conservatorium, then moved to Paris, composing vocal and instrumental works and orchestral pieces along with the operas “Irmelin” and “The Magic Fountain.”

His inspiration derived from the literature of England, Norway, Denmark, Germany and France, medieval romance, North American Indians and African-Americans, the Florida landscape and the Scandinavian mountainscape. His operatic masterpiece was “A Village Romeo and Juliet,” followed by “Appalachia,” “Sea Drift” and “A Mass of Life.” Then came “Songs of Sunset,” “Brigg Fair,” “In a Summer Garden,” the opera “Fennimore and Gerda,” “An Arabesque,” “The Song of the High Hills” and from 1911-12 came the popular “On hearing the first cuckoo in spring” and “Summer night on the river.” He produced many more concertos and orchestral/choral works.

Delius was a lifelong freethinker. He was “always ready to poke fun at the religious beliefs of his friends” (Grieg and Delius: A Chronicle of their Friendship in Letters by Lionel Carley.) In a letter to Edvard Grieg, Delius wrote, “I think the only improvement that Christ and Christianity have brought with them is Christmas. As people really then think a little about others. Otherwise I feel that he had better not have lived at all. The world has not got any better, but worse & more hypocritical, & I really believe that Christianity has produced an overall submediocrity & really only taught people the meaning of fear.” (Carley)

Close friend Eric Denby wrote an intimate biography in 1936 of Delius’s final years. “He had no faith in God,” Fenby wrote, “Nevertheless … my admiration for Delius’s music will in no wise have suffered thereby.” Fenby, a strong believer, often found himself a helpless punching bag for Delius’s criticisms of religion. “God? I don’t know him. Given a young composer of genius, the surest way to ruin him is to make a Christian of him.”

Delius married the German artist Jelka Rosen, a friend of Auguste Rodin and a regular exhibitor at the Salon des Indépendants, in 1903. They shared a passion for the works of Nietzsche and Grieg and moved to Grez-sur-Loing, a village 40 miles from Paris, where they lived together for the rest of their lives except for a period during World War I. They had no children and he was not a faithful husband, which Jelka seemed to accept. Delius was increasingly affected by the symptoms of syphilis that he had probably contracted in the 1880s. By 1928 he was partially paralyzed and blind. He died at age 72 in 1934. She died the next year and they share a grave in England. (D. 1934)

“The sooner you get rid of all this Christian humbug the better. The whole traditional concept of life is false. Throw those great Christian blinkers away, and look around you and stand on your own feet. … Don’t believe all the tommyrot priests tell you; learn and prove everything by your own experience.”

— Delius, quoted in "Delius As I Knew Him" by Eric Denby (1936)