May 16

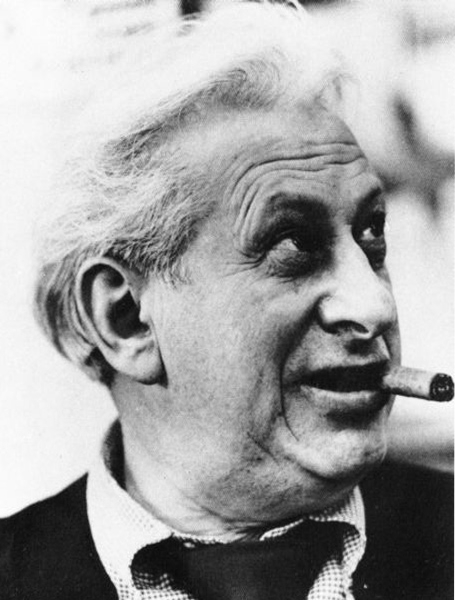

Louis “Studs” Terkel

On this date in 1912, Louis Terkel was born in the Bronx, N.Y., the third son of Samuel Terkel, a tailor, and the former Anna Finkel, an emigrant from Bialystok, Poland. A spirited man, he called himself an agnostic. Life was about life, not looking ahead to death, said Terkel, who spent most of his 96 years on Earth in Chicago.

As an actor in the theater he took the name Studs, after James T. Farrell’s fictional Studs Lonigan. He earned degrees in law and philosophy, was part of the Federal Writers’ Project and worked in radio drama and scriptwriting. He created his own radio show in 1945, a blend of music, interviews and commentary.

“Studs’ Place,” his first TV show, went on the air in 1950 but was soon canceled due to NBC’s nervousness about Terkel’s left-wing politics. He was back on the radio before long at WFMT, where his on-air career flourished for decades. He interviewed Bertrand Russell in Wales in 1962 when Russell was 90. “In the course of nature, I will soon die,” Russell told him. “My young friends have the right to many fruitful years. Let them call me fanatic.”

Division Street: America (1966) was Terkel’s first best-seller and became the blueprint for other literary oral histories like Hard Times, Working, The Good War, Race and Coming of Age. All told, he wrote 18 books. The last (in 2008) was P.S.: Further Thoughts From a Lifetime of Listening. Terkel told AARP magazine (March/April 2006), “I think we’re capable of extraordinary things, human beings. I call that God-like.” He died at home in Chicago at age 96. (D. 2008)

“TIPPETT: So, you know, one thing that is very striking that I didn’t expect is that this book, your book about death, it’s really a very religious book.

TERKEL: Religious book?

TIPPETT: Yes. I mean, there’s a lot of religion in it, all the way through it. I mean, did you know that, that those themes would be so prominent when you started it?

TERKEL: Well, I knew religion would play a role when I — to be fair, I happen to be an agnostic. You know what an agnostic is, don’t you?

TIPPETT: Oh, yeah.

TERKEL: A cowardly atheist. And I’m an agnostic. … You asked about the afterlife. Well, I can’t take bets on it. Who’s going to take my bet, you know? I, myself, don’t believe in any afterlife. I do believe in this life, and what you do in this life is what it’s all about.”— Interview with Krista Tippett on "Speaking of Faith," American Public Media, 2004

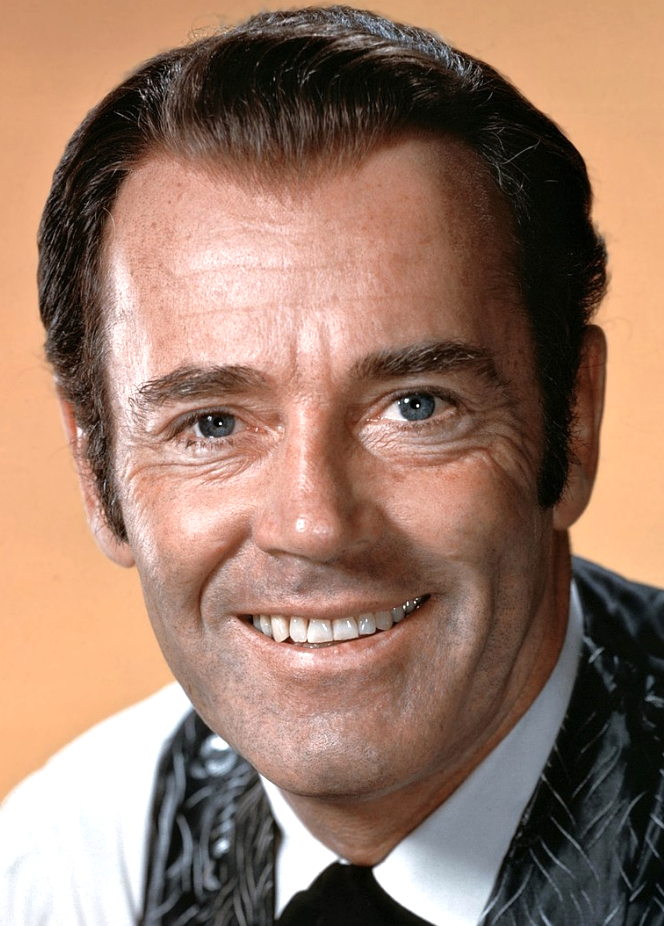

Henry Fonda

On this date in 1905, actor Henry Jaynes Fonda, the oldest of three children, was born in Grand Island, Neb., to William Brace Fonda and Herberta Krueger Jaynes. Although raised as a Christian Scientist, according to his biography, Fonda: My Life, written by Howard Teichmann in collaboration with Fonda, “[Fonda] claims to be an agnostic. Not an atheist but a doubter.” “My father was an agnostic,” wrote Jane Fonda in her autobiography, My Life So Far (2005).

Although he studied journalism in college, Fonda quit school and worked briefly in sales. At 20, Fonda started acting at the Omaha Community Playhouse. Between 1926 to 1934 he was in a myriad of theatrical productions before finally making his Hollywood debut in 1935, where his career took off. Fonda was nominated for an Academy Award for his performance in “The Grapes of Wrath” (1941). He won a Tony Award for his part as a junior officer in “Mister Roberts” (1948).

In 1957 he acted in and produced “12 Angry Men,” for which he shared the Academy Award and Golden Globe nominations with co-producer Reginald Rose, also winning the BAFTA Award for Best Actor for that film. Fonda was nominated for an Emmy for the TV movie adaptation of John Steinbeck’s novel, “The Red Pony” (1973). Returning to Broadway in 1974, he was nominated for a Tony Award for his riveting performance in the one-man show “Clarence Darrow.”

Although failing in health, Fonda continued acting in both TV and film, winning the Cecile B. DeMille Award for Lifetime Achievement in 1980. In 1981, he received a Lifetime Achievement Award from the Academy, as well as Best Actor for his performance in “On Golden Pond.” He also picked up the Golden Globe award for Best Motion Picture Actor for that movie. Making more than 100 films during his lifetime, Fonda was best known for his roles as the plain-speaking idealist. He was the father of three children, Jane and Peter Fonda, and their younger sister, Amy, and was the grandfather of actress Bridget Fonda. (D. 1982)

PHOTO: Fonda in a 1959 studio publicity shot for the movie “Warlock.”

“There had never been any renunciation of religion on my part, but like so many people, it was a gradual fading away.”

— Fonda, quoted in "Fonda: My Life" by Howard Teichmann (1981)

Brian Eno

On this date in 1948, Brian Peter George Eno was born in Woodbridge, England, and grew up in rural Suffolk. He graduated from the Winchester School of Art in 1969, where he studied painting. Eno felt that his work was influenced by avant-garde music, but did not go into music because he didn’t play an instrument.

He did work with sound by using cassette tapes and synthesizers, and in 1971 he joined the group Roxy Music, where he manipulated sound and sang backup. Eno’s on-stage garb in the early portion of his career was influential on the growing glam rock scene. After Eno left Roxy, he went on to record several solo albums.

In 1975 he developed the idea of ambient music, which was designed to blend with the surroundings. Eno has worked as a producer on many albums, including several albums for both U2 and Coldplay and one collaboration with Paul Simon. He also works with generative music, or music that is created according to a rule, for example a computer program.

His 2006 work “77 Million Paintings” combined generative music with generative video for a viewing experience that will be different every time. Eno created the score for Peter Jackson’s 2009 film “The Lovely Bones.” He continues to compose and record imaginative music as of this writing in 2019. Eno’s “Reflection” (2017), an album of ambient, generative music, was nominated for a Grammy at 2018’s 60th Grammy Awards ceremony.

Eno referred to himself in a 2007 BBC interview about “77 Million Paintings” as “kind of an evangelical atheist, actually.” In an interview with FACT magazine (Aug. 4, 2012), he compared his work to religion: “Religion gives people a chance to surrender. And I think part of what happens to people when they come into one of my shows is that they practise this feeling of surrendering.”

In 1967 at age 18 he married Sarah Grenville and they had a daughter that year. After divorcing, he married his manager Anthea Norman-Taylor in 1988. They have two daughters, Irial and Darla.

“Basically, Abrahamic religion belongs to the Middle Ages, and we’re moving beyond that now. We’re moving beyond wanting religion to do things it used to do. It used to have an explanatory role, but science has taken that place. It used to be the main source of beauty and awe, but art has taken that role. It used to be the main source of sanctions, but law has taken that role. What remains is what primitive people use it for – consolation and community-building.”

— Eno interview with Jules Evans, History of Emotions Blog (June 19, 2013)

Jean Hanff Korelitz

On this date in 1961, novelist Jean Hanff Korelitz was born in New York City to Ann and Burton Korelitz. She was raised in “an extremely progressive environment” by her Jewish parents. Her physician father specialized in gastroenterology and her mother was a therapist. Korelitz describes herself as “a lifelong atheist, but deeply tortured by ethical guilt and moral compulsion.” (The Guardian, July 23, 2021)

Korelitz credits her “love of psychopaths” to her mother, with whom she would “dissect” clients’ stories over the dinner table: “She had a vested interest in indoctrinating my sister and me with this information because she wanted us not to fall prey to the devastating charm of these people.” (Ibid.)

Life-changing for her was “D’Aulaires’ Book of Greek Myths” (1962): “The book that made me an atheist at the age of eight, while filling me with a passion for stories and art.” Her favorite book as a child was “anything involving a horse,” and the closing lines of Anna Sewell’s “Black Beauty” (1877) captured her imagination. (Shelf Awareness, Feb. 24, 2014)

After graduating from the private Fieldston School (started by Felix Adler, founder of the Ethical Culture movement), she earned an English degree from Dartmouth College and a master’s in English from Clare College in Cambridge, England. Her first novels — “A Jury of Her Peers” (1996) and “The Sabbathday River” (1999) — were filled with legal intrigue.

Novels that followed: “The White Rose” (2006), “Admission” (2009, with a 2013 film adaptation starring Tina Fey), “You Should Have Known” (2014, with a 2020 HBO film titled “The Undoing” with Nicole Kidman and Hugh Grant), “The Devil and Webster” (2017), “The Plot” (2021), “The Latecomer” (2022) and “The Sequel” (to “The Plot,” 2024).

Korelitz and Irish poet Paul Muldoon were married by a rabbi in 1987 at her parents’ home in South Salem, N.Y., and have a daughter, Dorothy (b. 1992) and a son, Asher (b. 1999). Muldoon won the 2003 Pulitzer Prize for Poetry and has taught since 1987 at Princeton University.

Korelitz and her sister Nina in 2015 co-produced “The Dead, 1904,” an immersive theater adaptation of James Joyce’s short story “The Dead.” Korelitz and Muldoon adapted the story for performance Off-Broadway by the Irish Repertory Theatre.

While long an open atheist, she is fascinated by religion, and Mormonism perhaps most of all. (For proof, watch her 15-minute “riff and rumination” on the House of SpeakEasy’s “Seriously Entertaining” series in 2023): “I can’t speak for all atheists but this one is fascinated by other people’s religious faith. … I think that’s because even though I’m pretty sure I’m right and I think we should all be atheists, part of me still believes that if you believe you are better than I am, and I can’t really explain that, but it means that even terrible people who I could name who are maybe in Congress right now, who are religious believers and who do terrible, terrible things are somehow better than I am because they have made this bargain with the unknown.”

PHOTO: Korelitz at the 2014 Texas Book Festival in Austin; photo by Larry D. Moore, CC 4.0.

“More important than the fact that I’m not a Mormon is the fact that I’m an atheist, and I became an atheist at the age of 8.”

— House of SpeakEasy's "Seriously Entertaining" (Jan. 10, 2023)

Jennifer Ouellette

On this date in 1964, science writer and editor Jennifer Ouellette was born in Ashland, Wis. “I was raised evangelical, and growing up, ‘secular humanist’ was pretty much synonymous with Satan. No truly good person could possibly be a humanist because all good comes from God. Or so I was taught.” (Speech to American Humanist Association, May 18, 2018)

“I thought everyone was adopted when I was a kid: You just go to the baby store and you get a baby. I didn’t know anything about my biological parents until I was in college. When I looked at the description of my biological mother, I thought: ‘Damn, I’m just like her in so many ways.’ ” (Psychology Today, Jan. 1, 2014)

After high school, she enrolled at Seattle Pacific University, founded by the Free Methodist Church, a conservative denomination, where she earned a B.A. in 1985. “I’m not a scientist by training. I’m a former English major who staunchly avoided taking physics, in any form, all through high school and college, only to run smack into it as a struggling freelance writer in New York City. And I found it wasn’t nearly as scary and inaccessible as I’d expected.” (Interview with science fiction author John Scalzi, June 20, 2007)

For about a decade after graduation, Ouellette was a contributing editor of The Industrial Physicist magazine, published by the American Institute of Physics. As a writer, she found her niche by focusing on how science meets culture, including in movies, TV and books. She directed the National Academy of Sciences’ Science and Entertainment Exchange from 2008-10 and wrote a blog for Scientific American titled “Cocktail Party Physics.”

Her physicist husband Sean M. Carroll (they married in 2007) explained that she was hired by the American Physical Society “after they found out that it was easier to teach physics to people who knew how to write than to teach writing to people who knew physics.” (Meet the Skeptics, Dec. 4, 2012)

Ouellette, who has a black belt in jiu-jitsu, was named senior science editor at Gizmodo in 2015 and joined Ars Technica in 2018 as a contributor and senior editor in 2024. She has published four popular science books: “Black Bodies and Quantum Cats: Tales from the Annals of Physics” (2005), “The Physics of the Buffyverse” (2006), “The Calculus Diaries: How Math Can Help You Lose Weight, Win in Vegas, and Survive a Zombie Apocalypse” (2010) and “Me, Myself And Why: Searching for the Science of Self” (2014).

She is “always looking for innovative ways to communicate the beauty and relevance of science – all science, not just physics – to people like me, for whom the traditional physics curriculum is, frankly, a bit of a turn-off. My brain just doesn’t work that way, but it doesn’t mean that I’m mentally challenged; rather, I just need a different approach to grasp the fundamental concepts of science.” (Ibid., Scalzi)

Long an advocate for death with dignity legislation, she talked about losing her brother when she accepted the Humanist of the Year award in 2018 from the American Humanist Association. He died of metastasized esophageal cancer (which Christopher Hitchens also succumbed to in 2011).

“David was really scared about his impending death — who wouldn’t be? But my evangelical Christian parents refused to admit that he was going to die. They had decided that Jesus was going to miraculously heal him, and any admission of the actual reality was akin to not having faith in their god’s power and greatness. This hurt David very deeply because he couldn’t talk to them about his feelings and what was happening to him.”

She added: “Humanists might appear to have a huge disadvantage when it comes to death and dying. We don’t have a rosy afterlife to point to, a reward in heaven to make up for all the suffering here on earth. Death is so very final. … But there is strength in facing that truth unflinchingly. Ironically, the humanists in the family dealt with David’s death far better than the devoutly religious members, precisely because we were willing to face the facts and grapple openly with a great personal loss.”

“I don’t need to tell anyone here that morality is not the exclusive domain of belief in a god. Anyone can live a good, fulfilling life, even without religion.”

— Ouellette, accepting AHA's Humanist of the Year award (May 18, 2018)