September 27

Albert Ellis

On this date in 1913, Albert Ellis was born in Pittsburgh, Pa. He graduated from the City University of New York with a degree in business and later decided to earn a Ph.D. in clinical psychology from Columbia University. He worked as a psychotherapist, marriage and family counselor and sex therapist. He became chief psychologist of New Jersey in 1950.

Ellis initially practiced psychoanalysis but in 1953 he declared it unscientific and became what he called a “rational therapist.” In 1955 he formulated Rational Emotive Behavior Therapy (REBT), a type of short-term cognitive behavioral therapy that counseled patients to take action to improve their lives in the present instead of focusing on past experiences. He founded the nonprofit Albert Ellis Institute in 1964, which worked to promote REBT and make it accessible. REBT was considered a revolutionary change in psychotherapy. A 1982 study found that Ellis was considered more influential than such famous psychologists as Sigmund Freud and Carl Jung.

Ellis became a “firm atheist and anti-mystic” at age 12, according to his 2007 book Are Capitalism, Objectivism, and Libertarianism Religions? Yes!. In the book, he also called himself a “probabilistic atheist,” meaning that he believed the probability of a god existing was very low. “We can have no certainty that God does or does not exist [but] we have an exceptionally high degree of probability that he or she doesn’t,” Ellis explained in his 2004 book, Rational Emotive Behavior Therapy: It Works For Me – It Can Work For You.

Ellis wrote “Case Against Religion: A Psychotherapist’s View and the Case Against Religiosity,” which was first published in The Independent in 1980 and later published as a pamphlet. He wrote that religion’s “absolutistic, perfectionistic thinking is the prime creator of the two most corroding of human emotions: anxiety and hostility.” D. 2007.

"For a man to be a true believer and to be strong and independent is impossible; religion and self-sufficiency are contradictory terms."

— Ellis, “Case Against Religion: A Psychotherapist’s View and the Case Against Religiosity,” 1980.

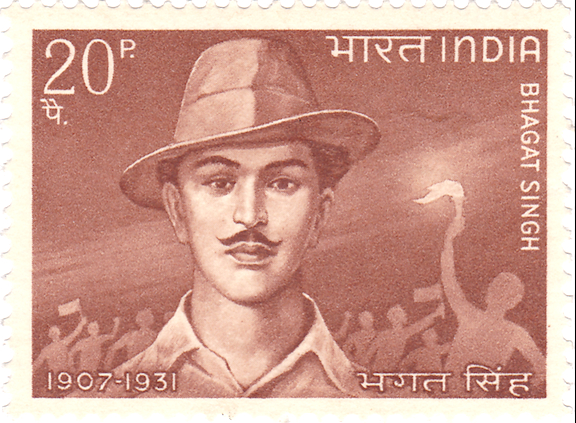

Bhagat Singh

On this date in 1907, Bhagat Singh, a revolutionary hero of the Indian independence movement, was born in Lyallpur (in current-day Pakistan). Although he’s revered almost universally in India, few of his admirers know that he was an avowed atheist and Marxist.

Singh was part of a family of freedom fighters and quickly acquired a radical consciousness. In 1928 he was convicted of conspiring to kill a British police officer in revenge for the beating death of an elderly independence stalwart, Lala Lajpat Rai. Singh escaped from the assassination scene only to reappear at the Punjab state Assembly building some months later, setting off bombs and shouting slogans.

Singh was willingly arrested with his comrade Batukeshwar Dutt. He was hanged by the British authorities along with two other co-conspirators on March 23, 1931, rendering him “immortal” in the eyes of his fellow Indians. He is remembered all across India and glorified in movies, TV shows, plays and songs. Singh was of Sikh background but became disillusioned with religion by his early youth. A turning point was religious unrest in his hometown of Lahore. He wrote articles analyzing the deleterious role that religion was playing in preventing Indians from coming together to oust the British.

His seminal essay on the issue was composed in prison in response to friends who thought his unbelief stemmed from vanity. In “Why I Am an Atheist,” written while he was facing execution, Singh patiently explained why he stopped believing in God and challenged every major Indian religion: “By the end of 1926 I had been convinced as to the baselessness of the theory of existence of an almighty supreme being who created, guided and controlled the universe. I had given out this disbelief of mine, I began discussion on the subjects with my friends. I had become a pronounced atheist.”

Singh offers a paradox in present-day India, where a man is venerated but his freethought and radicalism are conveniently ignored. A postage stamp with his image was issued in 1968. An 18-foot statue of him stands tall in the Indian Parliament, and his cremation site has been designated as the National Martyrs Memorial, but there are few takers for his ideas.

Singh’s proud embrace of atheism, even in the face of imminent death, presents a possible way out of the religious nationalism that has been bedeviling the country. D. 1931.

“One friend asked me to pray. When informed of my atheism, he said, ‘During your last days you will begin to believe!’ I said, ‘No, dear sir, it shall not be. I will think that to be an act of degradation and demoralization on my part.’ "

— Singh, "Why I Am an Atheist" (Oct. 5-6, 1930)

Robert Phillips

On this date in 1929, scientist and inventor Robert Matthews Phillips was born in Arcadia, Calif., the fourth of five children born to Annette (Matthews) and Edward Ashley Phillips. One month later, stocks started their deep decline, ushering in the Great Depression.

His father was an economics professor at the University of Southern California, where he met Phillips’ mother, who was majoring in language and later taught high school Spanish before becoming a stay-at-home mom. Just as the Depression loomed, his father was terminated at the insistence of the alumni association for giving deservedly low grades to academically underperforming athletes, threatening their football eligibility.

The family subsisted on the proceeds from a chicken/egg ranch and an acre of land devoted to growing fruits and vegetables. “My mother was a devout Methodist and my father was a lukewarm Presbyterian,” Phillips recalled. “She would read passages from the bible to us before we went to sleep. By the tender age of 7, I was convinced that these bible passages were based on fiction.” But overall, despite the economic challenges, his childhood was quite happy.

The family’s prospects turned positive after his father went to work for the Internal Revenue Service and Phillips was able to enroll after high school at the California Institute of Technology in Pasadena. He graduated from Caltech in 1952 with a B.S. in electrical engineering and joined General Electric’s advanced engineering program in Schenectady, N.Y., where he met Helen Cascio. They married in 1957 and have three daughters: Laura, Carol and Roben. They celebrated their 65th anniversary in 2022.

Phillips had transferred to GE’s microwave lab division in Palo Alto, Calif., in 1956. He invented the ubitron a year later, a vacuum tube that was the most powerful microwave amplifier of its time. In recognition of his pioneering work, he received the Free-Electron Laser Prize in 1992.

Today’s free-electron lasers employ the same basic principle as the ubitron. They produce powerful electromagnetic radiation used to explore the dynamics of chemical bonds, understand photosynthesis, analyze how drugs bind with targets and create warm, dense matter to study how gas planets form.

His career continued with research and management positions at GE, Varian and Eimac. He started a solar products company called Solartronics in 1975 and helped develop Star Microwave in 1991. In the mid-1990s, he joined the Stanford Linear Accelerator operated by Stanford University in Menlo Park, Calif., as a researcher. He retired there in 2005.

“I love the beauty and purity of mathematics and science and marvel at the inventions and understanding that unfold as we delve into scientific research,” Phillips said.

PHOTO: Phillips in the mid-2000s; photo courtesy of the Phillips family.

“There is so much yet to discover, and I am perplexed and frustrated by religion, which holds humanity back from its potential to evolve and to discover by clinging to improbable stories that deny evolution and so many observable and verifiable truths.”

— Phillips email to FFRF at age 92 (July 16, 2022)