January 11

Aldo Leopold

On this date in 1887, wildlife ecologist Rand Aldo Leopold was born in Burlington, Iowa, the eldest of four in a family of Lutherans who rarely attended church. Leopold earned his master of forestry from Yale University in 1909, worked in the Southwest, then transferred to the Forest Products Laboratory, in Madison, Wis. He became professor of game management at the University of Wisconsin in 1933 and chair of its new wildlife management department in 1939.

Leopold married a Catholic, Estella Bergene, in 1912, and they had five children. His church-going was limited to being married in one and attending his daughter Nina’s wedding. Beyond that, he believed “there was a mystical supreme power that guided the Universe, but to him this power was not a personal God. It was more akin to the laws of nature,” according to biographer Curt Meine (Aldo Leopold: His Life and Work, 1988).

In the 1930s he acquired a worn-out farm near Baraboo, Wis., dubbed “the Shack,” as a weekend retreat. He applied his respect for living lightly on the land and for “harmony between people and the land” to restore it. It remains the only “chicken coop” listed on the National Register of Historic Places. His influential book A Sand County Almanac, composed of sketches of nature and philosophical essays, was published posthumously in 1949. He suffered a fatal heart attack at age 61 while helping a neighbor put out a grass fire near Baraboo. (D. 1948)

PHOTO: Courtesy of USFS Forest Products Laboratory

“He thought organized religion was all right for many people, but did not partake of it himself.”

— "Aldo Leopold: A Fierce Green Fire" by Marybeth Lorbiecki (1996)

Alice Paul

On this date in 1885, feminist Alice Stokes Paul was born in Moorestown, N.J., to a Quaker family which believed in the equality of the sexes. She attended Swarthmore College, then spent a year as a student at the New York School of Philanthropy while working at a settlement house. Paul earned a master’s degree from the University of Pennsylvania in economics and sociology, then won a fellowship to study in England. She took courses at the University of Birmingham and London School of Economics and worked in the British settlement movement.

Paul was arrested and jailed several times in England for joining in brick-throwing at government buildings and took part in hunger strikes. Returning to New Jersey in 1910, she lectured in favor of adopting the British militancy. That year she stopped speaking to Quaker groups after her views were repudiated by them and transferred her allegiance to pure feminism. Like Quaker-raised Susan B. Anthony, Paul became an agnostic, according to Warren Allen Smith in Who’s Who in Hell. Her story inspired the 2004 HBO film “Iron Jawed Angels” in which she was portrayed by Hilary Swank.

Teaming up with her New York friend Lucy Burns, Paul talked the National American Woman Suffrage Association into letting them take over its congressional committee with help from Jane Addams, in 1912. They set up shop in Washington, D.C., organizing a historic parade of suffragists on March 3, 1913, upstaging the inauguration of President Woodrow Wilson. Peacefully parading women were attacked by a violent mob, which created huge headlines and reinvigorated the suffrage campaign.

During World War I, Paul and supporters picketed the White House with placards asking “How Long Must Women Wait for Liberty?” When mobs attacked, police arrested more than 100 suffragists, many of whom were sentenced to notorious workhouses. Paul and other hunger strikers were force-fed, and she was even transferred to a psychiatric hospital. The public outcry forced Wilson to unconditionally release the women. Demonstrations continued and Congress finally enacted the suffrage amendment, ratified by the states in 1920.

Paul went to law school, earning three degrees, then began promoting the Equal Rights Amendment, which she called the Lucretia Mott Amendment. Many women’s groups at the time, including the League of Women Voters and Women’s International League for Peace and Freedom, opposed the ERA on the grounds that women needed protective legislation. The amendment was first introduced into Congress in 1923. Paul lobbied for it in every successive session until 1972, when it passed. The combined forces of the tax-exempt religious lobbies defeated the ratification process in 1982 after it failed to gain support in the required number of states.

Paul, who never married, died at age 92 at a Quaker facility in New Jersey, less than a mile from her birthplace. (D. 1977)

PHOTO: Paul in 1915.

“Equality of rights under the law shall not be denied or abridged by the United States or by any state on account of sex.”

— From the Equal Rights Amendment drafted by Alice Paul and Crystal Eastman

G.W. Foote

On this date in 1850, atheist activist George William Foote was born in England. In 1876 he began co-editing a weekly newspaper, The Secularist, with Jacob Holyoake, then became the first editor of the National Secular Society’s publication The Freethinker. Foote edited The Freethinker for 35 years. The magazine is still published but moved to online-only in 2014.

Foote was prosecuted for blasphemy in 1882 and jailed for a year. His plight brought reform, making future criticism of Christianity lawful in Great Britain. Foote launched several other freethought journals, publishing companies and presses, devoting his life and career to the advancement of secularism. His books include Flowers of Freethought and, with W.P. Ball, The Bible Handbook. (D. 1915)

“Who burnt heretics? Who roasted or drowned millions of ‘witches’? Who built dungeons and filled them? Who brought forth cries of agony from honest men and women that rang to the tingling stars? Who burnt Bruno? Who spat filth over the graves of Paine and Voltaire? The answer is one word — Christians.”

— Foote from "Are Atheists Wicked?" (a chapter in "Flowers of Freethought," 1894)

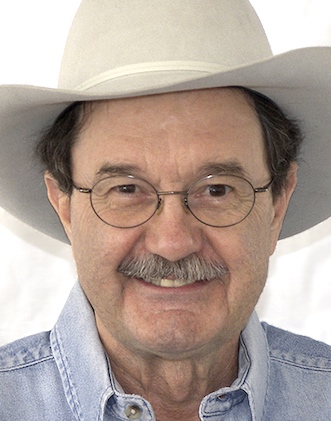

Jim Hightower

On this date in 1943, James Allen Hightower — author, columnist and political commentator — was born to working-class parents in Denison, Texas, where he grew up near the Oklahoma border. He’s perhaps most widely known for the quote “There’s nothing in the middle of the road but yellow stripes and dead armadillos,” also the title of his 1997 book.

“We considered ourselves the first line of defense against the ‘Okies’ there and I was raised in a small-business family. My mother and father both had come off of tenant farms,” he said. (Texas Legacy Project, April 9, 2002)

He worked while attending the University of North Texas State as assistant general manager of the Denton Chamber of Commerce and as a management trainee for the U.S. State Department. He served as student body president before earning a B.A. in government and later did graduate work at Columbia University in New York in international affairs.

He worked as an aide to U.S. Sen. Ralph Yarborough, a Texas Democrat, and then co-founded the Agribusiness Accountability Project in Washington before becoming editor in 1976 of the Texas Observer in Austin. He was elected state agriculture commissioner in 1982 and served until 1990, when he was defeated by Rick Perry. He launched Hightower Radio — a daily, syndicated two-minute commentary — in 1993 and it continues as of this writing in 2024 in conjunction with his print columns via the Creators Syndicate.

A monthly newsletter, The Hightower Lowdown, has over 40,000 subscribers. His views are progressive/populist, and he doesn’t hesitate to comment about religion: “In one of their satirical songs, the Austin Lounge Lizards lampooned the ridiculous bigotry of some Christian factions, singing: ‘Jesus loves me. But he can’t stand you.’ ” (El Dorado News-Times, Dec. 3, 2023)

Commenting on a Louisiana law mandating display of the Ten Commandments in public school classrooms, he wrote: “For us Texans, there’s nothing new about Bible-thumping politicians bedeviling us with the foolishness of their dogmatic Christian piety. A century ago, for example, a proposal was made to offer bilingual education to Spanish-speaking school kids. But it was quashed by the governor, who solemnly declared: ‘If English was good enough for Jesus Christ, it ought to be good enough for the children of Texas.’ ” (Creators Syndicate, July 3, 2024)

“Being an agitator is what America is all about. If it was not for the agitators of circa 1776, we’d all be wearing powdered wigs and still be singing ‘God Save the Queen.’ ” An agitator, he added, “is the center post in the washing machine that gets the dirt out.” (Americans Who Tell the Truth online biography)

Hightower accepted FFRF’s Clarence Darrow Award (video here) at its 2022 convention in San Antonio. In a speech titled “Progressives need more agitators,” he said: “It seems to me we’ve got to get out there and reach out to people, and then to try to unify them, because whether our particular issue is our labor rights or women’s rights, or climate change, abortion, or freedom from religion, our fundamental values come down to those issues of fairness and justice and opportunity for all.”

PHOTO: Hightower at the 2008 Texas Book Festival in Austin; photo by Larry D. Moore under CC 4.0.

“It makes me happier than a mosquito in a nudist colony to be standing up here, looking out at all of you.”

— Hightower to attendees at FFRF’s national convention in 2022