humorists

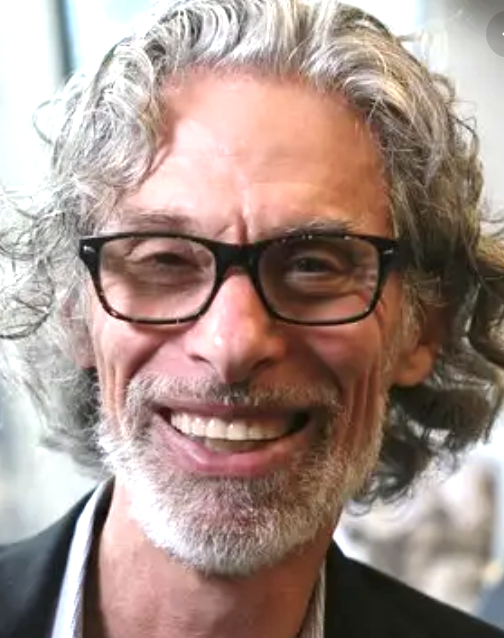

Scott Dikkers

On this date in 1965, humorist and entrepreneur Scott Dikkers was born in Minneapolis. While attending the University of Wisconsin-Madison, he started drawing a comic strip called Jim’s Journal that gained a small measure of local notoriety. He parlayed that into an unpaid spot on the staff of The Onion, a student humor newspaper started in 1988. The next year, he and Peter Haise bought the paper and started expanding it in terms of content and circulation beyond Madison.

The Onion’s small staff (described in one story as a “lone Jew surrounded by a collection of lapsed Lutherans and lapsed Catholics”) focused on making the mundane both irreverent and hilarious. A fair amount of that irreverence lands on religion’s shoulders. “Christians Growing Impatient for Third Coming of Christ” was the headline on one story. There are many, many others.

The Onion went online in 1996, which vastly increased its audience and renown. Dikkers co-wrote and edited The Onion’s first original book, Our Dumb Century, a best-selling spoof of recent history through Onion front pages, and Our Dumb World, a world atlas parody. In the mid-2000s, he spearheaded “The Onion News Network” web series, which won a Peabody Award in 2008 for its “ersatz news that has a worrisome ring of truth.”

That same year he addressed the Freedom From Religion Foundation’s national convention in Chicago. Dikkers was also included on Time magazine’s list of the Top 50 “Cyber Elite” along with Steve Jobs, Bill Gates, George Lucas and others. Headquarters moved to New York City in 2000-01 and to Chicago in 2012. The enterprise had been sold in 2003 to David Schafer. Dikkers remained as editor-in-chief from 2005–08 and is vice president for creative development as of this writing. Print publication ended in 2013.

He has written more than 20 humor books and developed the “Writing with The Onion” program at the Second City Training Center in Chicago. Described as reclusive and somewhat of a loner, he was, according to one story, married for a time, something that no one on the staff reportedly knew.

PHOTO by Brent Nicastro

“See, atheists and agnostics aren't scary. Listen to their laughter! It's a joyous sound, like the laughter of innocent children. You can trust us!

Furthermore, I want to say to the world, you need us. As I hope I've demonstrated here, atheists are fun. We're fun to be with. We like playing make believe as much as the next guy, but we know the difference between fantasy and reality. And our crucial role in society is to remind everyone else of the cold, hard facts.”— Dikkers' speech to FFRF's national convention (Oct. 12, 2008)

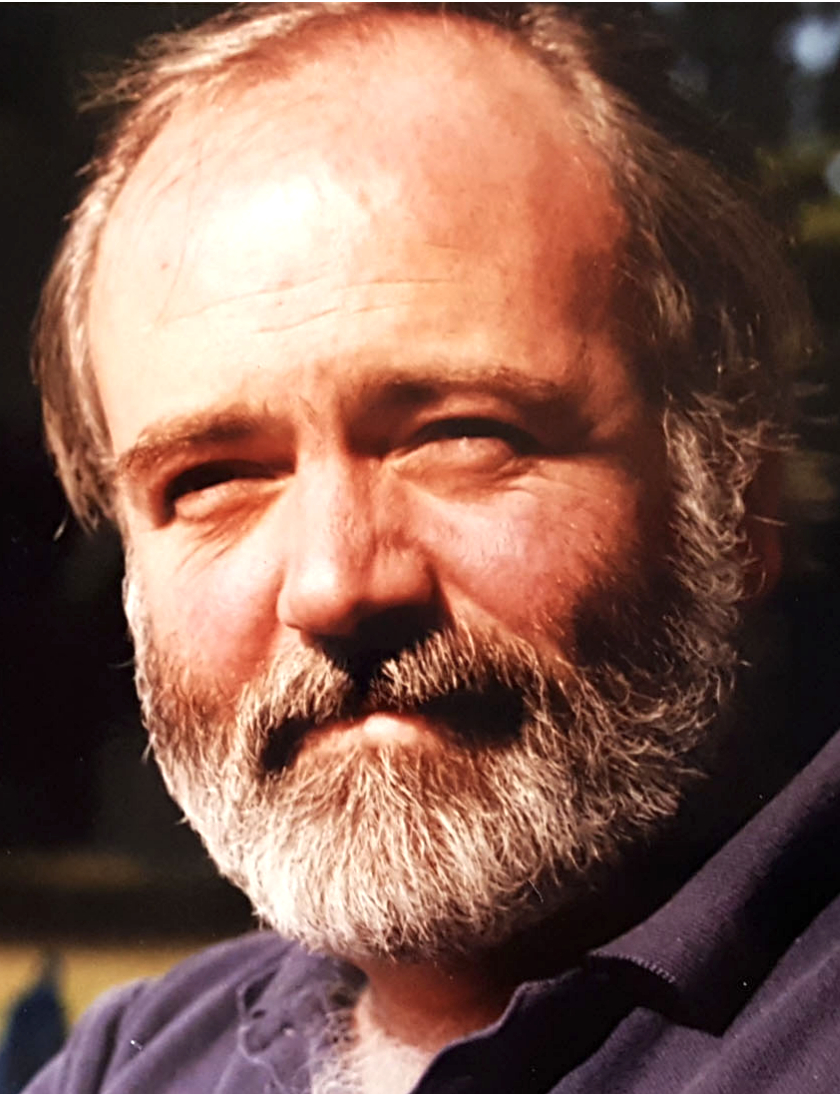

Bob Mankoff

On this date in 1944, Robert “Bob” Mankoff, cartoonist, writer and humor enthusiast, was born in New York City. Mankoff grew up in the borough of Queens in a Jewish family. Mankoff graduated from Syracuse University in 1966. He then attended Queens College to pursue a doctorate degree in experimental psychology, but found that his passion was humor.

For two years he submitted around 500 cartoons to The New Yorker without success. After his first submission was published 40 years ago, more than 900 of his cartoons have appeared in The New Yorker. He began The Cartoon Bank in 1991, a database of rejected New Yorker cartoons, which licenses cartoons to use in various media such as textbooks, magazines and newsletters.

The New Yorker purchased the bank in 1997, when he was named New Yorker cartoon editor, where he stayed for 20 years until stepping down in 2017. In 2018 he launched CartoonCollections.com as an archive and online store featuring the cartoons of over 70 illustrators.

Mankoff is credited with creating one of the most reprinted cartoons in The New Yorker’s history. It depicts a businessman at his desk talking on the phone while reviewing his calendar, saying, “No, Thursday’s out. How about never. Is never good for you?” He occasionally pokes fun at religion. In one scene, a man standing in a crowded church entrance says, “Good sermon, Reverend, but all that God stuff was pretty far-fetched.” In another, an obviously Jewish cleric says on the phone, “And remember, if you need anything I’m available 24/6.”

Mankoff has written several books, including his memoir How About Never: Is Never Good For You? My Life in Cartoons (2014) and The Naked Cartoonist: A New Way To Enhance Your Creativity (2002). He edited The Complete Cartoons of the New Yorker (2004) and several other New Yorker collections. He edited The New Yorker Encyclopedia of Cartoons: A Semi-serious A-to-Z Archive in 2018.

Mankoff has taught courses on the science and sociology of humor. He has partnered with the University of Michigan to conduct a series of experiments to study the role of humor in areas of economics, psychology and sociology.

After two prior marriages, Mankoff married Cory Scott Whittier in 1991. They live in New York and have a daughter, Sarah.

“Just to clear up any ambiguity, I'm not a believer, or even agnostic, I'm an atheist (denomination: Jewish). That means the God I don't believe in is different from the God you don't believe in if, for example, you're a Muslim atheist, a Catholic atheist, or a Protestant atheist."

— Mankoff column, "The cosmology of cartoonists," The New Yorker (May 1, 2013)

Ricky Gervais

On this date in 1961, Ricky Dene Gervais, was born. He makes TV shows and books and movies, but mostly he makes people laugh, and he makes them think, freely. (He’s an Honorary Associate of the National Secular Society and decided as a child that he was an atheist.) He grew up 40 miles west of London, England, in Reading, to working-class parents. He graduated from University College-London with a degree in philosophy and then worked in radio.

What eventually brought him fame were his television series “The Office,” which debuted in 2001, and “Extras,” in 2005. He co-wrote and co-directed both with Stephen Merchant, his friend and frequent collaborator. Gervais also played the lead roles of David Brent in “The Office” and Andy Millman in “Extras.” “The Office” was remade for audiences in France, Germany, Quebec and the U.S., where “Extras” premiered on HBO in 2005.

He played leading roles in the movies “Ghost Town,” “The Invention of Lying” and “Night at the Museum.” He’s had soldout standup comedy tours, wrote the best-selling “Flanimals” book series and starred with Merchant and Karl Pilkington in his podcast of “The Ricky Gervais Show.” He has been with his partner Jane Fallon since 1982.

He’s received two Golden Globes for “The Office” (one for acting, one for the show itself), as well as numerous British Academy Television Awards and British Comedy Awards. He won a 2007 Emmy Award for Outstanding Lead Actor in a Comedy Series for his role in “Extras.” In a conversation with Richard Dawkins, he explained how he became an atheist, recounting an afternoon at home when he was about 8. His mother was ironing and he was drawing Jesus on the cross as part of his bible studies homework.

His brother, Bob, 11 years older than Ricky, asked him why he believed in God, a question which mortified their mother. Gervais remembered thinking, “Why was that a bad thing to ask? If there was a god and my faith was strong, it didn’t matter what people thought. Oh … hang on. There is no God. He knows it, and she knows it deep down. It was as simple as that. I started thinking about it and asking more questions, and within an hour I was an atheist.”

Gervais hosted the Golden Globes award ceremony for a record fifth time in 2020. In 2011 he irreverently ended the show by saying, “Thank God I’m an atheist.”

“It’s always better to tell the truth. The truth doesn’t hurt, and saying that, my mother only ever lied to me about one thing. She said there was a God. But that’s because when you’re a working-class mum, Jesus is like an unpaid babysitter. She thought if I was God-fearing, then I’d be good.”

— "Inside the Actors Studio," Bravo TV (Jan. 12, 2009)

Dave Barry

On this date in 1947, author and humorist David McAlister Barry was born in Armonk, N.Y. (home to IBM’s corporate headquarters). His father and grandfather were Presbyterian ministers, but Barry grew up attending an Episcopal church, where he was an altar boy, because Armonk had no Presbyterian congregation.

He recalled his dad as being “more of a social worker than like a pastor.” Barry was raised “sort of religious” but he really wasn’t and called himself an atheist. “It’s okay to believe whatever you believe as long as you don’t think that everyone has to believe it, and if you’re willing to laugh a little bit about your own beliefs, then it’s just going to be easier for everybody to get along with different beliefs.” (Barry, undated video on Big Think web portal)

He had a very happy, stable childhood with “the coolest parents in the world.” At Pleasantville High School, he was voted Class Clown in 1965, then graduated with an English major from Pennsylvania’s Quaker-affiliated Haverford College in 1969, the year he married Lois Ann Shelnut. (Later oft repeated: “Haverford College — Official Motto: No, not Harvard.”) He had two subsequent marriages: to Beth Lenox in 1976 (with a son Robert) and Michelle Kaufman in 1996 (with a daughter Sophie).

Barry worked as a newspaper reporter, editor and columnist until 1975, when he joined Burger Associates, a consulting firm that taught effective business writing. “He spent nearly eight years trying to get various businesspersons to for God’s sake stop writing things like ‘Enclosed please find the enclosed enclosure,’ but he eventually realized that it was hopeless.” (Author bio, davebarry.com)

In 1983 he started an association with the Miami Herald that lasted until 2004. It was there he developed his chops as a widely syndicated humor columnist. He received the 1988 Pulitzer Prize for Commentary “for his consistently effective use of humor as a device for presenting fresh insights into serious concerns.” Other finalists were Molly Ivins, Ira Berkow and Michael Kinsley.

“I always worry when I start thinking my work has to have meaning,” he later wrote. “I don’t write to help people, I write to be funny. Listen, I’d be happy if my column always ran on the comics page, then it would be clear my only goal is entertaining.” (South Florida Sun-Sentinel, Oct. 20, 2001)

His lengthy Year in Review annual columns are reader favorites. From 2021: “The Capitol riot is widely condemned, with much of the blame falling on Trump. He swiftly receives the harshest punishment allowed under the Constitution: He is permanently banned from Twitter, the first sitting president to suffer this fate since Chester A. Arthur.”

One of his most recent books is proof that Barry strives to be silly. “A Field Guide to the Jewish People” (2019), co-written with Alan Zweibel and Adam Mansbach, has an explanatory blurb: “Who they are, where they come from, what to feed them, what they have against foreskins.” He’s published over 40 fiction and nonfiction books, including ones for young adults and children.

From 1993-97, CBS aired the sitcom “Dave’s World” based on his books “Dave Barry Turns 40” and “Dave Barry’s Greatest Hits.” It starred Harry Anderson as Barry and DeLane Matthews as his wife Beth. He identifies politically as a Libertarian and has run several less-than-serious presidential campaigns.

PHOTO: Barry at age 63 in Washington in 2011; Amazur photo under CC 3.0

THE FEDERALIST: You mention that you're not a believer in God. Are you a Christopher Hitchens-God-is-the-cause-of-all-the-troubles-in-the-world atheist or an agnostic? Do you see any value in religion?

BARRY: I don't think God is the cause of all the troubles in the world, because I don't think there's a God. I think religion causes a lot of problems, although I've known a lot of people — my dad, for example — who did a lot of good because of their religious faith.— Interview, The Federalist (April 3, 2014)

Jack Ziegler

On this date in 1942, satirist and cartoonist Jack Ziegler was born in Brooklyn, N.Y. He grew up in Forest Hills, Queens, in a Catholic household. His mother was a homemaker and his father sold pigment for a paint company. Ziegler developed an interest in cartoons at a young age, buying used comics on outings to Times Square. After graduating from Fordham University with a degree in communication arts, Ziegler joined the Army Reserve in Monterey, Calif.

While working at CBS network transmission facility, he started selling cartoons to various publications. The first cartoon he sold to The New Yorker was an illustration of Edgar Allan Poe contemplating which animal should say “Nevermore” — a turtle, moose or pig. His cartoons began appearing regularly in The New Yorker in 1974 and he was widely credited with bringing new life to the magazine.

Former cartoon editor Bob Mankoff described his drawings as “the platonic ideal of what a cartoon should look like.” During his lifetime he produced over 24,000 cartoons and sold over 3,000.

Ziegler also published several anthologies of drawings, including Hamburger Madness, How’s the Squid?: A Book of Food Cartoons; Olive or Twist?: A Book of Drinking Cartoons; and You Had Me at Bow Wow: A Book of Dog Cartoons. Most of his published work and personal papers are housed at the Billy Ireland Cartoon Library and Museum at Ohio State University.

He married his first wife, Jean Ann, in 1969 and they had three children: Jessica, Benjaim and Maxwell. After divorcing, he married Kelli Gunter in 1996. He died at age 74 while living in Lawrence, Kansas. (D. 2017)

"Agnostic, I suppose, but it's not something I ever think about. Raised Catholic, but stopped at age thirteen, when I realized what a load it was. Don't like any religions at this point — think they're all nuts to one degree or another. And they cause way too much trouble in the world — as they always have.

— Ziegler, quoted in "The cosmology of cartoonists" by Bob Mankoff, The New Yorker (May 1, 2013)

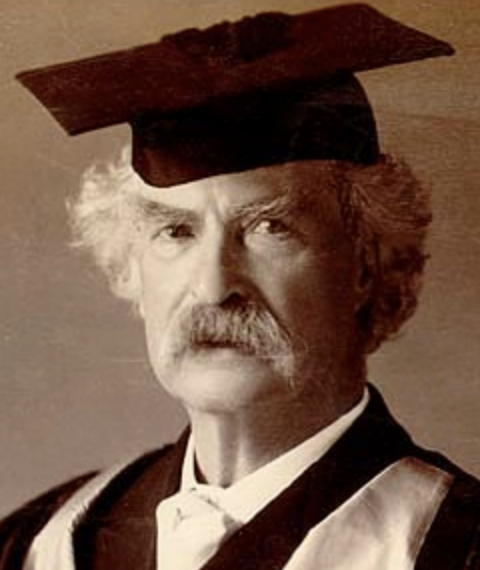

Mark Twain

On this date in 1835, America’s iconographic humorist and writer Mark Twain (né Samuel Langhorne Clemens) was born in Florida, Mo. He grew up in Hannibal, which became the inspiration for the setting of his classic books Tom Sawyer and The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn. His mother, Jane Lampton Clemens, was an advocate of the downtrodden and “could be beguiled into saying a soft word for the devil himself,” he recalled. His father died when he was 11. Samuel left school to work and by 13 was a journeyman printer at the Hannibal Gazette.

Traveling east to work as a printer and writer, he returned to Missouri to spend two eventful years as a cub pilot on the Mississippi River. His nom de plume was inspired by the call “mark twain” made to signal a safe passage of two fathoms’ depth. Twain worked as a reporter in Nevada and California. When his story “The Celebrated Jumping Frog of Calaveras County” was published, he became a national celebrity. He worked as a traveling correspondent and lecturer. Innocents Abroad was published in 1869.

After marrying Olivia Langdon in 1870, he built an opulent house in Hartford, Conn. It was at this home and at his sister-in-law’s farm in Elmira, N.Y., where he produced Tom Sawyer, The Prince and the Pauper, Life on the Mississippi and Huck Finn (1884). Twain’s later works included A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur’s Court (1889), “The War Prayer” (a scathing indictment of war and religious hypocrisy, written in 1905 but not published until 1923), The Mysterious Stranger (debunking Providence and published posthumously in 1916) and Letters From the Earth. His daughter Clara delayed publication of this blasphemous yarn told about humans from Satan’s perspective until 1962.

Europe and Elsewhere, containing “The War Prayer” and other freethinking writings, was edited by Albert Bigelow Paine, who also helped edit Twain’s autobiography published in 1923. Pudd’nhead Wilson (1894) begins each chapter with an aphorism from “Pudd’nhead Wilson’s Calendar,” including “There is no humor in heaven.” In Following the Equator (1897), he famously said, “Faith is believing what you know ain’t so.” Twain’s sardonic humor increasingly added indignant social criticism. He called the Book of Mormon “chloroform in print.” In 1907, he wrote Christian Science, exposing Mary Baker Eddy’s “desert vacancy, as regards thought.”

In the late 1890s he became a passionate critic of American imperialism, opposing the Spanish-American and Philippine wars. Twain suffered many personal tragedies, from his brother Henry’s tragic death in a steamboat accident in 1858, the death of his son Langdon at 19 months, the death of his daughter Susie from meningitis at age 24 and the death of his daughter Jean in an institution during an epileptic seizure. His wife Livy died in 1904. (D. 1910)

PHOTO: Twain in 1907 receiving a doctor of letters degree from Oxford University.

"I cannot see how a man of any large degree of humorous perception can ever be religious — except he purposely shut the eyes of his mind & keep them shut by force."— "Mark Twain's Notebooks and Journals, Notebook 27, August 1887-July 1888," ed. Frederick Anderson (1979)