February 27

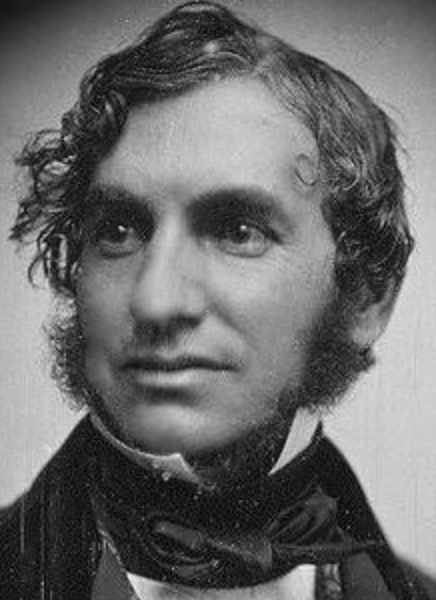

Henry Wadsworth Longfellow

On this date in 1807, Henry Wadsworth Longfellow was born in Portland, Maine, the son of an attorney who was also a member of Congress. Longfellow’s mother was a descendant of John Alden of the Mayflower. He started writing poems at 13 and graduated from Bowdoin College, where classmates included Nathaniel Hawthorne.

Longfellow traveled widely, married twice (both wives dying tragically) and became professor of modern languages at Harvard. He was the 19th century’s most popular American poet. His poems included “The Village Blacksmith” and “Paul Revere’s Ride,” as well as “Evangeline” (1847) and “The Song of Hiawatha” (1855).

William Ellery Channing reputedly said of Longfellow, a lifelong Unitarian, that “he did not belong to any one sect but rather to the community of those free minds who loved the truth.” A father of six children, he died at age 75 in Cambridge, Mass. (D. 1882)

PHOTO: Longfellow, circa 1850.

“I think that as he grew older his hold upon anything like a creed weakened, though he remained of the Unitarian philosophy concerning Christ. He did not latterly go to church.”

— William Dean Howells, "Literary Friends and Acquaintance; a Personal Retrospect of American Authorship" (1901)

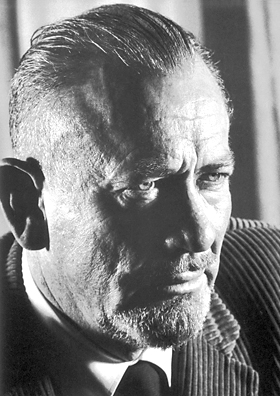

John Steinbeck

On this date in 1902, author John Ernst Steinbeck Jr. was born in Salinas, Calif. He studied marine biology at Stanford but did not graduate. His long list of humanistic novels includes the classics Of Mice and Men (1937) and The Grapes of Wrath (1939), which won a Pulitzer Prize. He also wrote Tortilla Flat (1935), The Red Pony (1937), Cannery Row (1945), East of Eden (1952) and The Winter of Our Discontent (1961), 33 books in all. He was awarded the 1962 Nobel Prize for Literature “for his realistic and imaginative writings, combining as they do sympathetic humour and keen social perception.”

Asked to complete a routine medical questionnaire for his new doctor, Steinbeck did so and added a letter dated March 5, 1964: “I shall probably not change my habits very much unless incapacity forces it. I don’t think I am unique in this. Now finally, I am not religious so that I have no apprehension of a hereafter, either a hope of reward or a fear of punishment. It is not a matter of belief. It is what I feel to be true from my experience, observation and simple tissue feeling.” (Steinbeck: A Life in Letters, ed. Elaine Steinbeck, 1975)

He married Carol Henning in 1930, divorced in 1943; Gwyn Conger in 1943, divorced in 1948; and Elaine Anderson Scott in 1950, together until his death in in New York City at age 66 from congestive heart failure. He had two sons with his second wife. (D. 1968)

“Literature was not promulgated by a pale and emasculated critical priesthood singing their litanies in empty churches — nor is it a game for the cloistered elect, the tinhorn mendicants of low calorie despair.”

— Steinbeck, Nobel Prize acceptance speech (1962)

Sonia Johnson

On this date in 1936, Sonia Ann Johnson, née Harris, was born a fifth-generation Mormon in Malad, Idaho. She graduated from Utah State University and married Rick Johnson, then pursued her M.A. and Ed.D. degrees from Rutgers University. She taught English at American and foreign universities, working part-time as a teacher while accompanying her husband on overseas jobs.

The family returned to the U.S. in 1976, buying a house in Virginia, one of the states that had not ratified the Equal Rights Amendment. Johnson became such an ardent supporter of the ERA that she was excommunicated by the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints in 1979. She exposed the role of the wealthy Mormon Church in sabotaging passage of the ERA. She went on a 37-day hunger strike in the Illinois statehouse in 1982 during the last days of the ERA countdown to symbolize how “women hunger for justice.”

Johnson ran on a feminist ticket for U.S. president in 1984 as the candidate of the Citizens Party, becoming the first third-party candidate to qualify for primary matching funds. In countless speeches, she pointed out, “Nobody’s ever fought a revolution for women.” She wrote eloquently of her experiences in From Housewife to Heretic (1981). In a 1982 speech to the Freedom From Religion Foundation, she said, “I have to admit that one of my favorite fantasies is that next Sunday not one single woman, in any country of the world, will go to church. If women simply stop giving our time and energy to the institutions that oppress, they would have to cease to do so.”

Her marriage ended amid tensions around her ERA advocacy and she started a feminist collective in an old monastery near Albuquerque, N.M. Membership dwindled until only she and Jade DeForest were left. They moved to Arizona and have been together ever since, according to a news story in the Salt Lake Tribune (Jan. 19, 2019).

Johnson, who is estranged from her four children, last published a book in 2010, The SisterWitch Conspiracy.

“Did I believe in God? The answer was no. All my conventional beliefs fell off me like a big, sloppy, unnecessary overcoat, and my real self emerged.”

— Johnson, on leaving Mormonism behind, Salt Lake Tribune interview (Jan. 19, 2019)

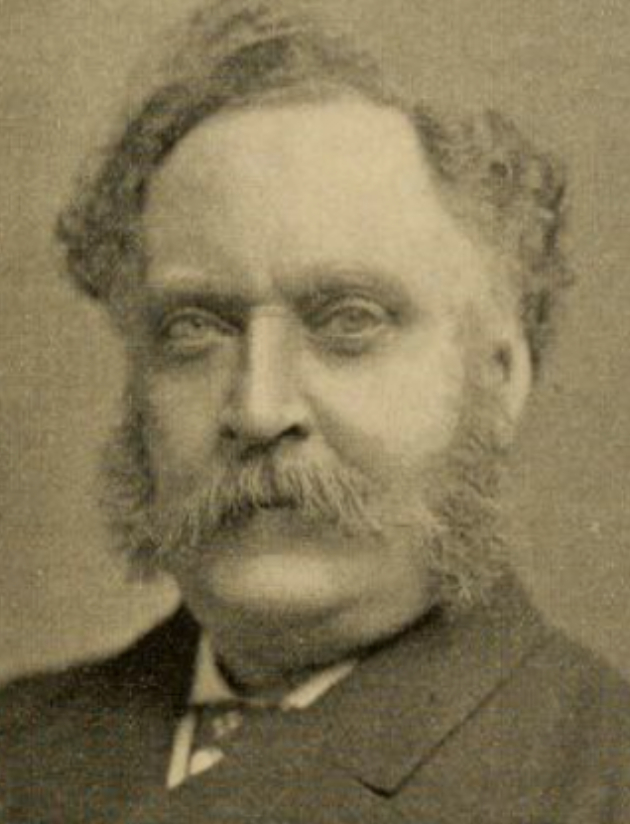

Charles Watts

On this date in 1836, Charles Watts was born in Bristol, England, into a family of Methodists. At age 16 he moved to London to work with his older brother in a printing office. The brothers were acquainted with many freethinkers and founded a publishing business, Watts & Co., in 1864. Along with Charles Bradlaugh and others, Watts co-founded the National Secular Society in 1866.

Watts wrote extensively on freethought, including Freethought: Its Rise, Progress and Triumph (1885). In an 1868 pamphlet on Christianity, he wrote: “In Spain religion is cruel oppression, in Scotland it is a gloomy nightmare, in Rome it is priestly dominion, while in England it is simply emotional pastime. All these different phases of Christianity indicate that theological opinions depend on surrounding circumstances, and cannot therefore be the cause of the civilisation of the world.”

He emigrated to Toronto in 1883, where he lectured and became the leader of the secularist movement in Canada. Returning to England in 1891, he worked for The Freethinker, the world’s oldest surviving freethought publication (internet-only since 2014). Watts’ wife, Kate Eunice Watts, also wrote and traveled with him. Some of her writings included The Education and Position of Woman and Christianity: Defective and Unnecessary.

Watts died at age 70 and was cremated, with his remains buried in Highgate Cemetery in North London. His son, Charles Albert Watts, developed the Rationalist Press Association, still in existence as the Rationalist Association. (D. 1906)

“The object of Christ was to teach his followers how to die, rather than to instruct them how to live.”

— from Watts' pamphlet "Christianity: Its Nature and Influence on Civilisation" (1868)

Peter De Vries

On this date in 1910, satirical novelist Peter De Vries was born in Chicago to Dutch immigrant parents who were devout Christian Reformed Church members. He attended elementary and secondary church schools. His father envisioned his son’s future as a clergyman and convinced him to enroll at Calvin College in Grand Rapids, Mich., where he instead studied English and played basketball.

After graduation he returned to Chicago and sold candy on a vending-machine route, worked for a small newspaper, acted on the radio and in 1938 joined Poetry magazine, first as an associate editor, then as co-editor. He met his soon-to-be wife, Katinka Loeser, in 1943 when she won an award from the magazine. They would have four children.

That was also the year he joined the New Yorker, working with James Thurber, Robert Benchley, S.J. Perelman and Dorothy Parker. De Vries’ specialty was writing cartoon captions. He was so adept at linking verbal pith to illustrations that many New Yorker cartoons started in reverse, with images commissioned to match his captions. His 1954 novel The Tunnel of Love, later a Broadway play and a movie starring Doris Day, featured a character with talents similar to De Vries’.

De Vries wrote prolifically: short stories, reviews, poetry, essays, plays, novellas and 23 novels. “De Vries was one of the United States’ funniest writers, but never remotely the most successful. He was extraordinarily inventive, a superb maker of plots, but he wrote in an era when linguistic virtuosity and verbal comedy were increasingly undervalued.” (The Independent, Oct. 3, 1993)

To philosopher Daniel Dennett, he was “probably the funniest writer on religion ever.” Novelist Kingsley Amis wrote in 1956 that De Vries was “the funniest serious writer to be found either side of the Atlantic.” Calvin College professor James Bratt called De Vries “a secular Jeremiah, a renegade CRC [Christian Reformed Church] missionary to the smart set.”

He’d grown up forbidden to watch movies, dance or play cards. As De Vries put it, “We were the elect, and the elect are barred from everything, you know, except heaven.” (The American Interest magazine, March 1, 2010) Journalist Jonathan Hiskes, who also grew up in Chicago in the Reformed Church, writing in the journal Image, Issue 83: “Almost nobody spoke of De Vries when I was growing up. If anyone even mentioned him, they dismissed him as ‘that atheist writer.’ ”

Hiskes added: “Where Calvinists are reverent in matters of religion and silent in matters of sex, De Vries was the opposite.” Don Wanderhop, De Vries’ protagonist in The Blood of the Lamb (1961), tells a girlfriend: “Sometimes I think this leg is the most beautiful thing in the world, and sometimes the other. I suppose the truth lies somewhere in between.” He introduces another character with “She was about twenty-five, and naked except for a green skirt and sweater, heavy brown tweed coat, shoes, stockings …”

The Blood of the Lamb is autobiographical and is his darkest, most poignant novel. It ends with the death of Wanderhop’s young daughter. De Vries published it a year after his daughter Emily died of leukemia at age 10. In its climactic scene, Wanderhop rages at a god who lets children suffer and die: “How I hate this world. … I would like to dismantle the universe star by star, like a treeful of rotten fruit.”

De Vries was elected to the American Academy of Arts and Letters in 1983, the year Slouching Towards Kalamazoo was published. He died at age 83 in Norwalk, Conn., and was buried alongside his wife and daughter in Westport, Conn. His tombstone says, “Dying is hard, but comedy is harder.” (D. 1993)

“What baffles me is the comfort people find in the idea that somebody dealt this mess. Blind and meaningless chance seems to me so much more congenial — or at least less horrible. Prove to me that there is a God and I will really begin to despair.”

“It is the final proof of God’s omnipotence that he need not exist in order to save us.”

— First quote: Said by "militant atheist" Stein, who has a child in the cancer ward in "The Blood of the Lamb" (1961). Second quote: Said by the Rev. Andrew Mackerel of the People’s Liberal Church in "The Mackerel Plaza” (1958)