chemists

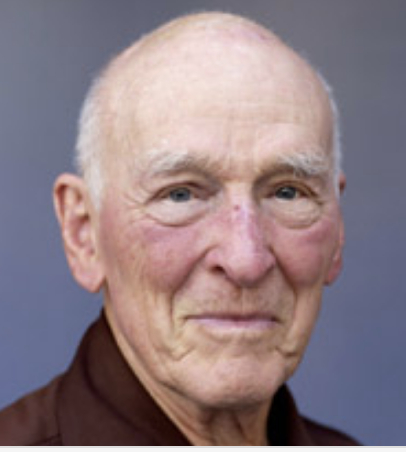

Paul D. Boyer

On this date in 1918, molecular biochemist Paul D. Boyer was born in Provo, Utah, the middle child in a family of six in a Mormon home. His mother’s death from Addison’s disease when he was 15 awakened his interest in studying biochemistry. He became a “deacon” in the Mormon church at age 12 and graduated from Brigham Young University, where he met his future wife Lyda Whicker (they would have three children). His pursuit of science during graduate studies at the University of Wisconsin-Madison altered his religious perspective. He earned his doctorate in 1943.

After moving to Stanford University to do postdoctoral research for a war project, he and Lyda stopped going to Mormon meetings. By the time he was 25 he had “slipped over from agnostic to atheist,” he told Freethought Radio in 2007, and Lyda also professed her atheism. In 1955 he went to Sweden on a Guggenheim Fellowship. Boyer spent 17 years as a faculty member at the University of Minnesota. He continued his work at UCLA in 1963 and became director of the newly created Molecular Biology Institute there in 1965. He would stay at UCLA for over half a century, studying enzymes, the proteins involved in biochemical processes in animal and plant cells.

Boyer shared the Nobel Prize in Chemistry in 1997 with John Waller and Jens Skow “for their elucidation of the enzymatic mechanism underlying the synthesis of adenosine triphosphate.” As his New York Times obituary later put it, he shared the prize “for his contributions to understanding the way all organisms get energy from their environments and process it to sustain life and fuel their activities.”

Boyer had pointed out that “belief in God and in a Hereafter dropped considerably as the level of scientific achievement increased.” In his Nobel autobiography he called himself as a “devout atheist” and added, “I wonder if in the United States we will ever reach the day when the man-made concept of a God will not appear on our money, and for political survival must be invoked by those who seek to represent us in our democracy.”

He became an advocate of death with dignity after the illness and death of his son Douglas in 2001. Boyer was an FFRF Life Member who spoke at the 2002 national convention in San Diego and outlined his “path to atheism” in a 2004 Freethought Today essay. He died less than two months shy of his 100th birthday. (D. 2018)

PHOTO by Brent Nicastro.

"My views have changed from a belief that my prayers were heard to clear atheism. … Over and over, expanding scientific knowledge has shown religious claims to be false.”

“None of the beliefs in gods has any merit."

— Boyer, "A Path to Atheism," Freethought Today (March 2004)

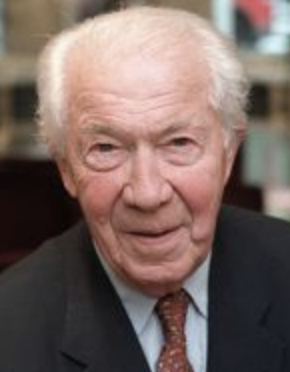

Christian de Duve

On this date in 1917, Nobel Prize-winning scientist Christian de Duve was born to Belgian parents in Surrey, England. He later moved to Belgium and during World War II served as a medic in the Belgian Army. He received his Ph.D. in chemistry in 1945 from the Catholic University of Leuven. His thesis focused on insulin, the chemical that regulates blood sugar and when not produced causes diabetes. He married Janine Herman in 1943. They had had two sons, Thierry and Alain, and two daughters, Anne and Françoise.

De Duve became a professor at the Catholic University of Leuven in 1947 and in 1962 also became associated with Rockefeller Foundation laboratories in New York City. His work focused on subcellular biochemistry, cell biology and the origin of life.

He discovered two types of cell organelles: peroxisomes and lysosomes. His research furthered understanding of genetic disorders such as Tay-Sachs disease. De Duve shared the 1974 Nobel Prize for Physiology or Medicine with Albert Claude and George Palade for their work on cell structure. The three are recognized as the fathers of the field of modern cell biology.

While raised Catholic, de Duve tended toward agnosticism if not outright atheism. He strongly supported biological evolution and dismissed creation science and intelligent design, as explicitly stated in his last book, Genetics of Original Sin: The Impact of Natural Selection on the Future of Humanity (2010). In declining health at age 95, he chose to end his life with the aid of two doctors. Euthanasia is legal in Belgium. (D. 2013)

"It would be an exaggeration to say I'm not afraid of death, but I'm not afraid of what comes after, because I'm not a believer."

— De Duve, explaining his choice to die using euthanasia (New York Times, May 6, 2013)

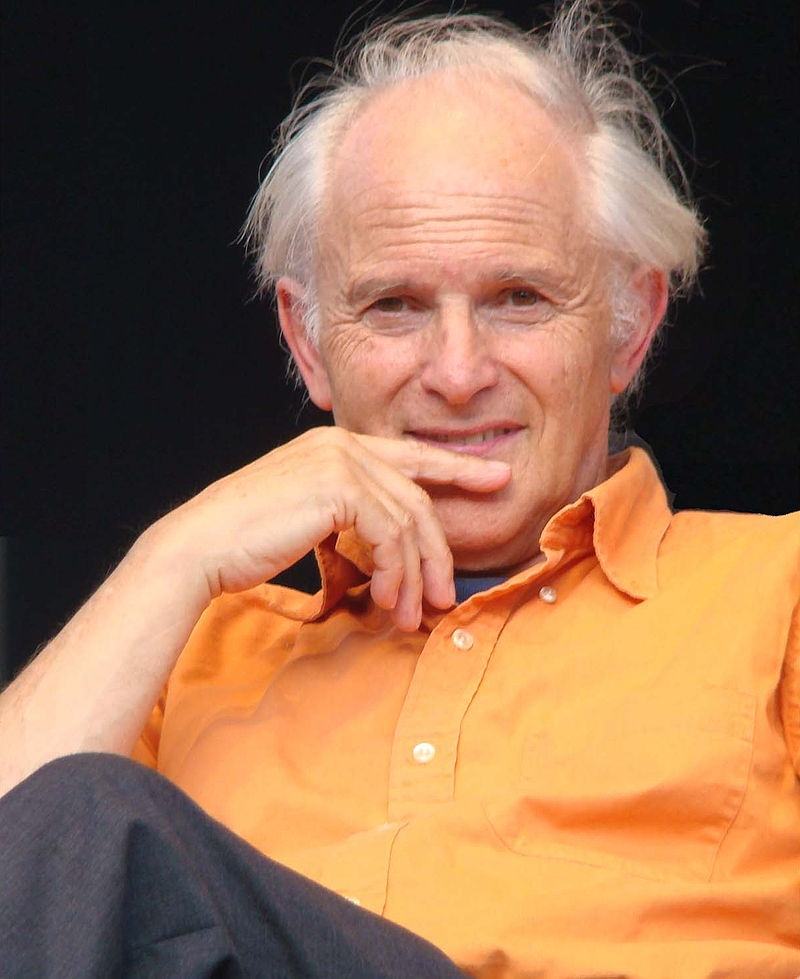

Harry Kroto

On this date in 1939, chemist Harold Walter “Harry” Kroto (né Krotoschiner) was born in Wisbech, Cambridgeshire, England. His parents were both German but had to leave Berlin in 1937 because his father was Jewish. Kroto attended Sheffield University to study chemistry, graduating with honors in 1961 and receiving his Ph.D. in 1964. He did postdoctoral research at the National Research Council in Canada and Bell Laboratories in the U.S.

He returned to England in 1967 to teach at the University of Sussex and research carbon chains in interstellar space. Aware of the laser spectroscopy work being done by Richard Smalley and Robert Curl at Rice University in Texas, Kroto contacted them and suggested they use the Rice apparatus to simulate the carbon chemistry that occurs in the atmosphere of a carbon star. The experiment supported their theory and revealed an unexpected result, the existence of a new molecule, the C60 species, aka buckminsterfullerene (buckyballs). The discovery earned Curl, Kroto and Smalley the shared Nobel Prize in Chemistry in 1996. “Sir” soon preceded his name when he was knighted that year.

In 2004 he joined the faculty at Florida State University as a professor of chemistry, where he continued his work on carbon and spearheaded the development of GEOSET (Global Educational Outreach for Science, Engineering and Technology). GEOSET is a growing online cache of video teaching modules that are available for free.

In 1963 he married Margaret Henrietta Hunter, also a student of the University of Sheffield. They had two sons, Stephen and David. A humanist and professed atheist, he once joked, “The only mistake Bernie Madoff made was to promise returns in this life.” (According to A.C. Grayling in The Guardian, July 1, 2009)

He died at age 76 in Lewes, East Sussex, from complications of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. (D. 2016)

PHOTO: By Pd1000 under CC 3.0.

“I am a devout atheist — nothing else makes any sense to me and I must admit to being bewildered by those, who in the face of what appears so obvious, still believe in a mystical creator.”

— From Kroto's Nobel Prize autobiography (1996)