american-revolution

‘Wall of Separation’ Phrase Coined

On this date in 1802, President Thomas Jefferson coined the famous phrase describing the Establishment Clause of the First Amendment as erecting “a wall of separation between church and state.” He used the phrase in his famous letter to the Baptists of Danbury, Connecticut, who had asked him to explain the meaning of the First Amendment’s phrase “Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion.”

“I contemplate with sovereign reverence that act of the whole American people which declared that their legislature should make no law respecting an establishment of religion, or prohibit the free exercise thereof, thus building a wall of separation between church and state.”

— Jefferson's letter to the Baptists of Danbury (Jan. 1, 1802)

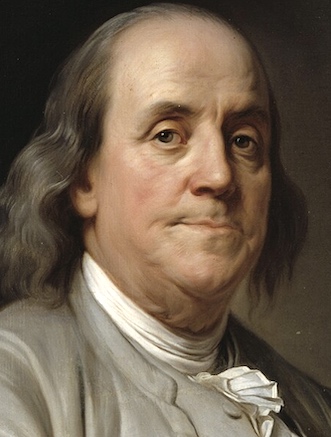

Benjamin Franklin

On this date in 1706, Benjamin Franklin was born. The Boston-born printer, publisher, inventor, author, aphorist and statesman quit the Presbyterian Church in 1734, according to his Autobiography. Franklin was a deist in the mode of the Enlightenment, retaining only a belief in a god and future life. After the Constitutional Convention of 1787 had been underway for a month, the octogenarian Franklin suggested that the so-far secular convention conduct a prayer. Records show that Franklin’s proposal created polite embarrassment, and that the convention adjourned without any vote on the motion.

Franklin was part of a distinguished committee, including Adams and Jefferson, which adopted the United States’ secular motto “E Pluribus Unum” (“Out of many, one”). At one point, the pragmatic Franklin suggested that currency should contain the phrase “Mind your business.” From 1732-58 he published the annual pamphlet “Poor Richard’s Almanac” using the pseudonym Richard Saunders. In the 1754 almanac he wrote, “When a religion is good, I conceive it will support itself; and when it does not support itself, and God does not take care to support it so that its professors are obliged to call for help of the civil power, ’tis a sign, I apprehend, of its being a bad one.” (D. 1790)

PHOTO: Painting c. 1785 by Joseph-Siffred Duplessis

“The way to see by Faith is to shut the eye of Reason.”

— Franklin, "Poor Richard's Almanac" (1758)

Thomas Paine

On this date in 1737, Thomas Paine was born in Thetford, Norfolk, England, emigrating to British colonial America in 1774. Paine wrote the pamphlet “Common Sense” in 1776, fanning the flames of the American Revolution. Paine is best known for his political writings. No better index to his character can be found than his reply to Ben Franklin’s remark, “Where liberty is, there is my country.” Paine replied, “Where liberty is not, there is mine.” Without the pen of Paine, said one contemporary, the sword of George Washington would have been wielded in vain.

A freethinker in the 18th-century mode of deism, although he never described himself as a deist, Paine wrote the classic criticism of the bible, The Age of Reason (1792), completing the second volume under arduous conditions of imprisonment in France. “I believe that religious duties consist in doing justice, loving mercy, and endeavoring to make our fellow creatures happy. I do not believe in the creed professed by the Jewish church, by the Roman church, by the Greek church, by the Turkish church, by the Protestant church, nor by any church that I know of. My own mind is my own church.”

He wrote that organized religion was “set up to terrify and enslave” and to “monopolize power and profit.” Paine repudiated the divine origin of Christianity on the grounds that it was too “absurd for belief, too impossible to convince and too inconsistent to practice.” He was vilified for his unabashed analysis of the bible when he returned to America in 1802. Even a century after his death, Theodore Roosevelt referred to Paine, the man who named the United States of America, as “a filthy little atheist,” ignoring the fact that Paine wrote in The Age of Reason, “I believe in one God, and no more; and I hope for happiness beyond this life.” In Rights of Man (1791) he wrote, “My country is the world, and my religion is to do good.”

Paine married Mary Lambert in 1759. She died in early labor a year later, along with the child. He married again in 1771 but legally separated three years later just before leaving for America. He died in New York City at age 72. (D. 1809)

“Whenever we read the obscene stories, the voluptuous debaucheries, the cruel and tortuous executions, the unrelenting vindictiveness, with which more than half the Bible is filled it would be more consistent that we call it the word of a demon than the word of God. It is a history of wickedness that has served to corrupt and brutalize.”

— Paine, "The Age of Reason" (1792)

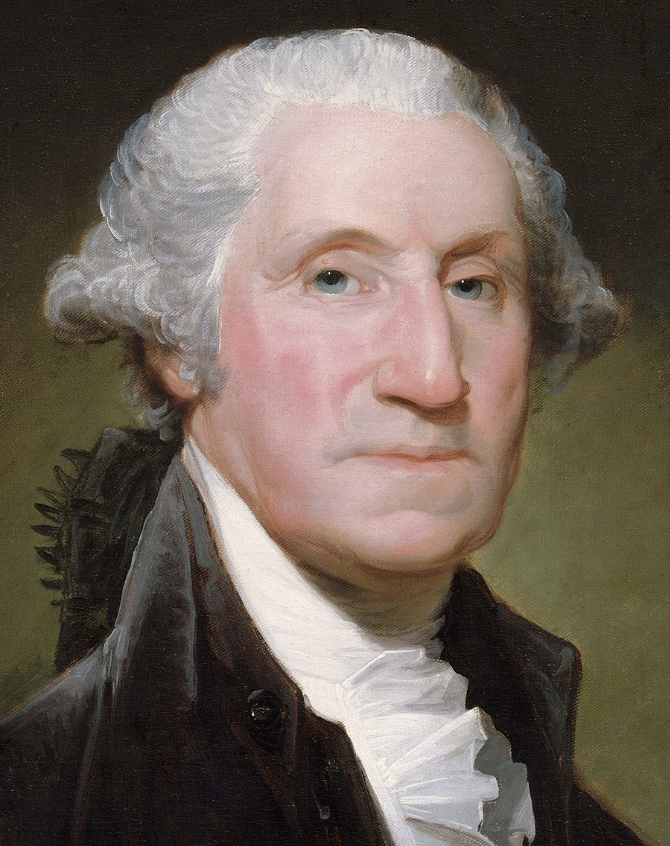

George Washington

On this date in 1732, George Washington was born in Popes Creek, Va., the eldest of six children. His father died when he was 11 and Washington inherited 10 slaves and a farm. He received a surveyor’s license in 1749 from the College of William & Mary and was appointed surveyor of Culpeper County. By 1752 he owned 2,315 acres of land.

Washington was elected to the Virginia House of Burgesses in 1758, was a delegate to the Continental Congress of 1774 and became commander of the Continental Army in 1775. He presided over the Constitutional Convention in Philadelphia in 1787, which adopted a godless constitution, and was elected the first U.S. president in 1789. He was reelected in 1793 and retired to Mount Vernon at the end of his second term. He married Martha Dandridge Custis in 1759 after her husband died when she was 25. Washington adopted her two children; two others had died.

Thought by many to be a deist, Washington has been claimed by many religions but kept his beliefs mostly to himself: “Religious controversies are always productive of more acrimony & irreconcilable hatreds than those which spring from any other source.” (Washington letter to Sir Edward Newenham, June 22, 1792.)

Jefferson recorded this on Feb. 1, 1800, in Memoir, Correspondence, And Miscellanies, From The Papers Of Thomas Jefferson, Vol. 4: “Doctor Rush tells me that he had it from Asa Green, that when the clergy addressed General Washington on his departure from the government, it was observed in their consultation, that he had never, on any occasion, said a word to the public which showed a belief in the Christian religion, and they thought they should so pen their address, as to force him at length to declare publicly whether he was a Christian or not. They did so. However, he observed, the old fox was too cunning for them. He answered every article of their address particularly except that, which he passed over without notice. Rush observes, he never did say a word on the subject in any of his public papers, except in his valedictory letter to the Governors of the States when he resigned his commission in the army, wherein he speaks of ‘the benign influence of the Christian religion.’ I know that Gouverneur Morris, who pretended to be in his secrets and believed himself to be so, has often told me that General Washington believed no more of that system than he himself did.”

The foremost mythmaker about Washington was Parson Mason Weems, whose Life of Washington (1800) promoted the cherry tree story and other disinformation, such as the claim that Washington prayed in the woods at Valley Forge in the Revolutionary War winter of 1777-78.

Propagandists allege Washington wrote a Christian prayer, which is engraved on a bronze tablet at St. Paul’s Chapel in New York City. The source is not a prayer, but a business letter to governors, which makes two orthodox, deistic references (The Writings of George Washington, ed. Worthington Ford, 1889). Washington’s diaries reveal that he seldom attended church and often traveled on the sabbath. (D. 1799)

PHOTO: Washington in 1795 in an oil painting by Gilbert Stuart (cropped).

“Of all the animosities which have existed among mankind, those which are caused by difference of sentiment in religion appear to be the most inveterate and distressing, and ought most to be deprecated. I was in hopes that the enlightened and liberal policy which has marked the present age would at least have reconciled Christians of every denomination, so far that we should never again see their religious disputes carried to such a pitch as to endanger the peace of society.”

— Washington letter to Edward Newenham, June 22, 1792, "The Writings of George Washington, Vol. XII"

James Madison

On this date in 1751, James Madison Jr. was born near Port Conway, Va., to James and Nelly Conway Madison. A deist, he became the primary author of the secular U.S. Constitution and Bill of Rights and the fourth U.S. president. Madison was elected to the first House of Representatives, was secretary of state under Thomas Jefferson and served as president from 1809 to 1817.

Baptized Anglican, he contemplated the ministry as a career. After graduating from the College of New Jersey (later renamed Princeton), Madison was appointed a delegate to the Virginia state convention. There he was responsible for the adoption of a freedom of conscience clause in the state constitution. “Religious bondage shackles and debilitates the mind and unfits it for every noble enterprise, every expanded prospect,” Madison wrote William Bradford on April 1, 1771.

After being elected to the Virginia Legislature, his famous “Memorial and Remonstrance” defeated a bid to force mandatory tithing in 1785. In it, he stated “it is proper to take alarm at the first experiment on our liberties.”

“During almost fifteen centuries has the legal establishment of Christianity been on trial. What have been its fruits? More or less in all places, pride and indolence in the Clergy, ignorance and servility in the laity, in both, superstition, bigotry and persecution.” (Memorial and Remonstrance Against Religious Assessments, June 20, 1785)

His “Detached Memorabilia,” written between 1817 and 1832, revealed his regrets over the appointment of chaplains to the two houses of Congress. Madison called it “a palpable violation of equal rights, as well as of Constitutional principles.” He equally argued against chaplains in the military and religious proclamations by the president, writing that such acts “imply a religious agency.”

In a letter to Louisiana attorney and legislator Edward Livingston, Madison wrote: “Every new & successful example therefore of a perfect separation between ecclesiastical & Civil matters is of importance. And I have no doubt that every new example will succeed, as every past one has done, in shewing that Religion & Govt. will both exist in greater purity, the less they are mixed together.” (July 10, 1822)

Madison married Dolley Payne Todd, a widow and 17 years his junior, in 1794, helping raise her son Payne. In 1826, after Jefferson’s death, Madison was appointed as rector of the University of Virginia. He retained the position as college chancellor for 10 years until his death at Montpelier at age 85 of congestive heart failure. (D. 1836)

“[T]he number, the industry, and the morality of the priesthood & the devotion of the people have been manifestly increased by the total separation of the Church from the State.”

— "The Writings of James Madison, Vol. VIII: 1808-1819," ed. Gaillard Hunt (1908)