March 19

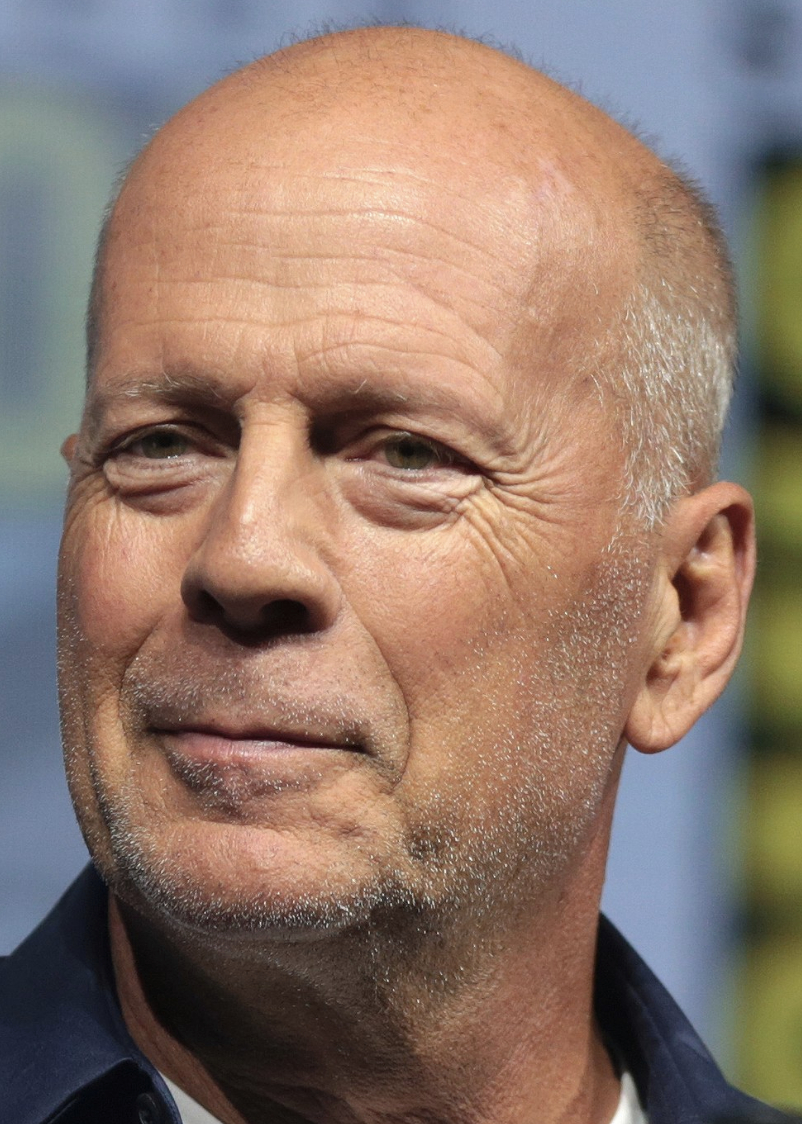

Bruce Willis

On this date in 1955, actor Walter Bruce Willis was born on a military base in Germany. He was raised Lutheran and grew up in Penns Grove, New Jersey, attended Montclair State College, then moved to New York City. Willis waited on tables and bartended while looking for acting jobs. He was cast for one of his first roles as a bartender by a director who spotted him tending bar. Willis’ TV break came in the series “Moonlighting” (1985). His first box office hit was “Die Hard” (1988).

Among his earlier movies are three “Die Hard” sequels, “Look Who’s Talking” (1989), “The Bonfire of the Vanities” (1990), “The Last Boy Scout” (1991), “Pulp Fiction” (1994), “Twelve Monkeys” (1995), “The Jackal” (1997), “Breakfast of Champions” (1999), “The Sixth Sense” and “The Story of Us” (1999). Since then he has made at least one movie every year as of this writing in 2022. He is the recipient of a Golden Globe, two Primetime Emmy Awards and two People’s Choice Awards. He received a star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame in 2006.

Willis was married from 1987 to 2000 to actress Demi Moore and married actress Emma Heming in 2009. He and Moore have three daughters, Rumer, Scout and Tallulah. He and Heming have two daughters, Mabel and Evelyn.

Willis’ family announced in March 2022 that he had retired from acting after being diagnosed with aphasia, a language disorder that affects the ability to communicate. It can be caused by a stroke, head injury, brain tumor or other disease.

PHOTO: Willis at the San Diego Comic-Con in 2018; Gage Skidmore photo under CC 3.0.

“Organized religions in general, in my opinion, are dying forms. They were all very important when we didn’t know why the sun moved, why weather changed, why hurricanes occurred, or volcanoes happened. Modern religion is the end trail of modern mythology. But there are people who interpret the Bible literally. Literally! I choose not to believe that’s the way.”

— Willis interview, George magazine (July 1998)

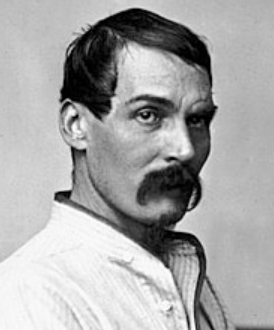

Sir Richard F. Burton

On this date in 1821, Sir Richard Francis Burton was born in Great Britain. The colorful adventurer and explorer, educated at Oxford, served in the army in India, where he began to study languages and Muslim culture. Burton became fluent in nearly 30 languages. Posing as a pilgrim, he was the first non-Muslim to partake in the rituals of Mecca, writing a book about the experience.

He made famous translations of the Arabian Nights and the Kama Sutra, and traveled extensively in the Mideast, Africa and South America. Biographers, including his niece, Georgiana Stisted (True Life of Sir R.F. Burton), considered Burton a rationalist, at most an agnostic or deist. He was married to a highly superstitious Catholic woman who had last rites administered at Burton’s death. (D. 1890)

“The more I study religions the more I am convinced that man never worshipped anyone but himself.”

— Burton, in "Terminal Essay" from his translation of "Arabian Nights" (1885)

Jean Astruc

On this date in 1684, Jean Astruc was born in France, the son of a Protestant minister who converted to Catholicism. Astruc, who became a physician, was one of the early founders of bible criticism. He served as professor of anatomy at Toulouse, then Montpellier, and later as professor of medicine at Paris. In 1753 he published his Conjectures.

Astruc was among the first to try to show that the Book of Genesis was based on several sources or manuscript traditions, an approach now called the documentary hypothesis. According to historian J.M. Robertson, he died without the sacraments. (D. 1766)

—

Henry Morgentaler

On this date in 1923, abortion doctor and pro-choice activist Henry Morgentaler, born Henryk Morgentaler, was born in Lodz, Poland. His parents were Jewish socialists. The Gestapo murdered his father in 1939 when the Nazis invaded Poland. Morgentaler, his mother and two siblings were forced to live in Lodz’s ghetto, where his sister died, until 1944. The Nazis then sent Morgentaler, his mother and his brother to Auschwitz, where they killed his mother and the brothers did forced labor until they were sent to Dachau, which Allied forces liberated in 1945.

He emigrated to Canada in 1950 and graduated from the University of Montreal’s medical school in 1953. He began his career as a general practitioner but transitioned to family planning when he saw the need. He performed his first abortion in 1968 and opened his first abortion clinic in Montreal in 1969.

“I decided to break the law to provide a necessary medical service because women were dying at the hands of butchers and incompetent quacks, and there was no one there to help them. The law was barbarous, cruel and unjust. I had been in a concentration camp, and I knew what suffering was. If I can ease suffering, I feel perfectly justified in doing so.” (Morgantaler: A Difficult Hero, by Catherine Dunphy, 1996.)

Morgantaler battled the Catholic Church, his clinics were raided by police and harassed by pickets and he was arrested four times for performing abortions. Each time he was acquitted by jurors but was sentenced to 18 months in prison when one of his acquittals was appealed. Morgantaler was released after 10 months when he suffered a heart attack.

Another acquittal that was appealed went to the Canadian Supreme Court, resulting in a historic 1988 decision overturning a law restricting abortions to hospitals and to those in which the pregnancy endangered the woman. Even in Canada, his actions were controversial and after several abortion doctors were attacked and even murdered, he took many safety precautions, including wearing a bulletproof vest.

He was active in humanist organizations in Montreal, and in 1975 the American Humanist Association made him its Humanist of the Year. He received many other honors and recognition for his work, including induction into the Order of Canada in 2008. Morgentaler married three times and divorced twice. He had four children: Goldie, Bamie, Yann and Benny. At the time of his death at age 90, he was married to Arlene Leibovich. (D. 2013)

PHOTO: rabbleradio under CC 2.0.

“In Canada, you have fewer religious fanatics, there is much less violence in Canada and it’s a much more tolerant society.”

— Morgentaler, quoted in “Sniper Attacks on Doctors Create Climate of Fear in Canada” (New York Times, Oct. 29, 1998)

Philip Roth

On this date in 1933, author Philip Milton Roth was born to Herman Roth and Bess (Finkel) Roth in Newark, N.J., where he grew up with an older brother. He encountered anti-Semitism at an early age and later wrote that his childhood love of baseball offered him “membership in a great secular nationalistic church from which nobody had ever seemed to suggest that Jews should be excluded.” At Bucknell University he decided the school’s “respectable Christian atmosphere [was] hardly less constraining than [his] own particular Jewish upbringing.”

After earning a master’s in English in 1955 from the University of Chicago, he taught there for two years and started writing short fiction. Roth published Goodbye, Columbus, a collection of short stories and the title novella, to critical acclaim in 1959. He then worked as a visiting lecturer at the University of Iowa Writers’ Workshop, followed by two years as a writer-in-residence at Princeton University. Letting Go (1962) was his first full-length novel. When She Was Good (1967), which Roth once called a “book with no Jews,” is also his only novel to feature a female protagonist.

He had married Margaret Martinson in 1956. They separated in 1963 and she died in a car accident in 1968. Martinson was the inspiration for female characters in several of his novels, including Lucy Nelson in When She Was Good. He didn’t marry again until 1990, when he wed English actress Claire Bloom. They divorced in 1995, after which she published a memoir that described their marriage in detail unflattering to Roth. Both marriages were childless.

Roth started teaching literature in the late 1960s at the University of Pennsylvania. The 1969 feature film adaptation of Goodbye, Columbus coincided with the publication of Portnoy’s Complaint, which soon became a best-seller amid controversy for its prurient content. (Those who’ve read it will likely not forget Portnoy’s “affair” with a slab of liver.) Roth’s works in the 1970s included a Richard Nixon parody titled Our Gang, The Breast, The Great American Novel and, what some consider his best novel, My Life as a Man. Three novels (The Ghost Writer, Zuckerman Unbound and The Anatomy Lesson) were published in one volume in 1985.

The 1990s saw publication of Deception, Patrimony: A True Story, Operation Shylock, Sabbath’s Theater and a trilogy consisting of American Pastoral (which won a Pulitzer), I Married a Communist and The Human Stain. He remained prolific after the turn of the century with The Dying Animal, The Plot Against America, Everyman, Indignation, The Humbling, Nemesis and Exit Ghost, the ninth book narrated by Zuckerman, Roth’s fictional alter ego.

Roth won a slew of writing awards besides the Pulitzer and eight of his novels were adapted for movies. He was awarded the 2010 National Humanities Medal by President Barack Obama at the White House in 2011. He died of congestive heart failure at age 85. (D. 2018)

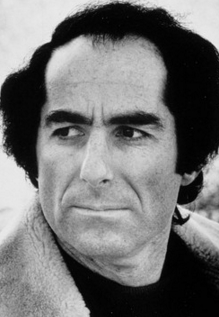

PHOTO: Roth in 1973.

“I’m exactly the opposite of religious, I’m anti-religious. I find religious people hideous. I hate the religious lies. It’s all a big lie. … I have such a huge dislike. It’s not a neurotic thing, but the miserable record of religion. I don’t even want to talk about it, it’s not interesting to talk about the sheep referred to as believers.”

“Do you consider yourself a religious person?”

“No, I don’t have a religious bone in my body,” Roth said.

“So, do you feel like there’s a God out there?” Braver asked.

“I’m afraid there isn’t, no,” Roth said.

“You know that telling the whole world that you don’t believe in God is going to, you know, have people say, ‘Oh my goodness, you know, that’s a terrible thing for him to say,” Braver said.

Roth replied, “When the whole world doesn’t believe in God, it’ll be a great place.”— Interview with Martin Krasnik of The Guardian (Dec. 14, 2005); interview with CBS News correspondent Rita Braver (Oct. 3, 2010)