June 17

Bible Reading in Public Schools Halted

On this date in 1963, the U.S. Supreme Court issued its decision in Abington Town School District v. Schempp, 374 U.S. 203, barring bible reading in public schools. The case, brought by Ed Schempp and his family, challenged a Pennsylvania law requiring that “at least ten verses from the Holy Bible shall be read, without comment, at the opening of each public school on each school day. Any child shall be excused from such Bible reading, or attending such Bible reading, upon the written request of his parent or guardian.”

Schempp, with his wife Sidney and two of their three children, brought suit. (The eldest, Ellery, graduated from high school so was dismissed from the case but was the original instigator of the complaint.) The religious exercises were broadcast into each class through a public address system and were conducted under the supervision of a teacher by students. They concluded with the Lord’s Prayer, with students asked to stand and recite the prayer in unison following a flag salute.

Joined to the Abington case was Murray v. Curlett, challenging a similar practice adopted by the Baltimore School Board requiring reading, without comment, a chapter from the “Holy Bible” and/or the Lord’s Prayer to open the school day. The Abington decision followed the 1962 Engel v. Vitale Supreme Court decision, ruling classroom prayer unconstitutional in public schools. Ed Schempp, who died in 2003, was a longtime member of the Freedom From Religion Foundation and an honorary officer.

“The place of religion in our society is an exalted one, achieved through a long tradition of reliance on the home, the church and the inviolable citadel of the individual heart and mind. We have come to recognize through bitter experience that it is not within the power of government to invade that citadel, whether its purpose or effect be to aid or oppose, to advance or retard. In the relationship between man and religion, the State is firmly committed to a position of neutrality.”

— Justice Tom Clark, majority opinion in Abington Town School District v. Schempp (1963)

Jello Biafra

On this date in 1958, musician Jello Biafra (né Eric Reed Boucher) was born in Boulder, Colo., to Virginia (Parker) Boucher, a librarian, and Stanley Boucher, a psychiatric social worker and poet. Biafra is one-eighth Jewish but was unaware of that until the mid-2000s. He grew up in a secular household.

After high school he worked as a roadie for a punk rock band, enrolled at the University of Southern California-Santa Cruz and co-founded a San Francisco group in 1978 that became the Dead Kennedys, known for its politically themed songs, some laced with profanity. He adopted his stage name, mixing the gelatin dessert Jell-O with the short-lived west African nation Biafra.

He and Dead Kennedys guitarist East Bay Ray started the independent record label Alternative Tentacles in 1979. It lost the rights to Dead Kennedys recordings after a 2000 lawsuit. Biafra wrote the lyrics for the band’s 1981 EP “In God We Trust, Inc.,” which scorned organized religion (“Religious Vomit”) and neo-Nazis, among other targets. The band broke up in the mid-’80s and he began recording spoken word albums, joined the group Lard and formed Jello Biafra and the Guantanamo School of Medicine, performing for the first time on his 50th birthday.

The band canceled a 2018 show in Tel Aviv due to political unrest over the Palestinian situation. Biafra ended up going by himself, and in an article titled “Thoughts On Visit to Israel” (alternativetentacles.com, 5-24-18) wrote: “I have heard many times on both sides of the pond that ‘The problem is not the Israeli Jews. It’s the right-wing American Jews.’ ” He continued: “The bottom line, as one person at the table put it — can democracy survive religion? ‘A little bit of God is a dangerous thing.’ ”

Biafra married singer Theresa Soder, stage name Ninotchka, on Halloween 1981 in a cemetery. The ceremony was officiated by Flipper vocalist/bassist Bruce Loose, who became a Universal Life Church minister to marry them. They divorced in 1986.

PHOTO: Biafra performing in 2010 in Hradec Kralove, Czech Republic; photo by yakub88 / Shutterstock.com

“I’m not religious, music is my higher power, and I never know what’s coming next.”

— Interview, Kerrang! magazine (Jan. 14, 2021)

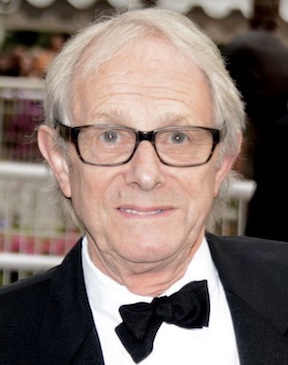

Ken Loach

On this date in 1936, filmmaker Kenneth Charles Loach was born in Nuneaton, Warwickshire, England, the son of working-class parents Vivien (née Hamlin) and John Loach. He joined the Royal Air Force at age 19 and later read law at St. Peter’s College-Oxford while participating in the Experimental Theatre Club.

He started working at the BBC in 1963 as a trainee television director. Loach became a critical darling in 1969 with his second feature film “Kes” about a troubled boy who turns to falconry to find fulfillment. The British Film Institute has listed it as the seventh best British movie ever.

He drew renewed attention in 1990 with “Hidden Agenda,” a thriller harshly critical of British policies in Northern Ireland. This was followed by “Riff-Raff” (1991) and “Raining Stones” (1993), which dealt with working-class issues, and “Land and Freedom” (1995), a highly moving dramatization of the Spanish Civil War.

With the help of screenwriter Paul Laverty, Loach went on to greater acclaim with movies such as “Carla’s Song” (1996), “My Name Is Joe” (1998), “Bread and Roses” (2000) and “Sweet Sixteen” (2002). Encyclopedia Britannica calls his films “landmarks of social realism.”

Two of his films — “The Wind That Shakes the Barley” (2006), about the Irish struggle for independence, and “I, Daniel Blake” (2016), about a man who survives a heart attack only to be stymied by bureaucracy — have won the Cannes Film Festival’s top prize, the Palme d’Or. Most recently as of this writing, Loach directed “The Old Oak” (2023), about Syrian refugees in England, which he has said will be his final film.

Loach married Lesley Ashton in 1962. They have two sons and two daughters. Another son died at age 5 in a car accident in 1971. He declined knighthood in 1977, and in a March 2001 interview said, “It’s all the things I think are despicable: patronage, deferring to the monarchy and the name of the British Empire, which is a monument of exploitation and conquest.”

Loach is a strong supporter of the British Humanist Association. On the Humanists UK website, he said: “Freedom of belief – or nonbelief – is a fundamental human right. Religious creeds and doctrine should play no part in our public life. In particular, the indoctrination of children in separate faith schools is pernicious and divisive.”

PHOTO: Loach at the 2014 Cannes Film Festival; photo by Georges Biard.

“I’m an agnostic. I can’t comprehend infinity, and so long as I can’t do that, I have to admit the limits of what the human mind, at least my mind, can imagine. So who am I to say? But the stories that religions tell, they seem to me to be fairy stories. The danger is that if we are concerned about an afterlife, we do not engage fully in the struggle to make this a better, safer, more just world for everyone.”

— Interview, New Humanist magazine (Aug. 8, 2024)