June 10

E.O. Wilson

On this date in 1929, biologist and author Edward Osborne Wilson was born in Birmingham, Ala. His father, Edward Osborne Wilson Sr., worked as an accountant. His mother, Inez Linnette Freeman, was a secretary. They divorced when he was 8. He had a nomadic childhood, mostly with his father, an alcoholic who would kill himself.

Wilson earned his B.S. and M.S. in biology from the University of Alabama and a Ph.D. in 1955 from Harvard, the same year he married Irene Kelley. They had a daughter, Catherine. He joined the Harvard faculty in 1956, where he retired in 2002 at age 73, although he published more than a dozen books after that.

Blinded in one eye by a fishing accident as a child, his research focus was in the field of myrmecology, the study of ants. He discovered the chemical means by which ants communicate. His books include The Insect Societies (1971) and The Ants (1990), co-written with Bert Holldobler, which won the 1991 Pulitzer Prize for nonfiction. Wilson’s On Human Nature won a Pulitzer in 1979.

Wilson is perhaps best known for his intellectual syntheses, often connecting evolution and biology to other disciplines. His 1967 book, The Theory of Island Biogeography, which develops the mathematics of how species evolve in geographically small habitats, is influential in the fields of ecology and practical conservation. He worked out the importance of habitat size and position within the landscape in sustaining animal populations.

In 1975 he published Sociobiology: A New Synthesis, which connected the evolution of social insects with other animals, including humans. At the time, the idea that human behavior is genetically influenced was very controversial and Wilson was criticized as racist and sympathetic to eugenics. During a 1978 lecture he had a pitcher of water poured on his head while the attacker exclaimed, “Wilson, you’re all wet.”

More recently, Wilson was criticized by Monica McLemore, an associate professor at UC-San Francisco, for espousing “theories fraught with racist ideas about distributions of health and illness in populations without any attention to the context in which these distributions occur.” She added that “what works for ants and other nonhuman species is not always relevant for health and/or human outcomes. For example, the associations of Black people with poor health outcomes, economic disadvantage and reduced life expectancy can be explained by structural racism, yet Blackness or Black culture is frequently cited as the driver of those health disparities. Ant culture is hierarchal and matriarchal, based on human understandings of gender. And the descriptions and importance of ant societies existing as colonies is a component of Wilson’s work that should have been critiqued. Context matters.” (Scienfic American, Dec. 29, 2021)

Wilson expanded on the ideas propounded in Sociobiology in On Human Nature (1978), which spawned the discipline of evolutionary psychology. While initially widely accepted with some enthusiasm, some aspects of evolutionary psychology research became even more controversial than Sociobiology, with the line between the two fields becoming more blurred.

Wilson’s parents were Southern Baptists though he was also raised by conservative Methodists. He abandoned Christianity before college, later describing himself as a “provisional deist” and agnostic. In On Human Nature, he argued that belief in God and rituals of religion are products of evolution. He disdained the tribalism of religion: “And every tribe, no matter how generous, benign, loving, and charitable, nonetheless looks down on all other tribes. What’s dragging us down is religious faith.”

In Esquire magazine (Jan. 5, 2009), Wilson said: “If someone could actually prove scientifically that there is such a thing as a supernatural force, it would be one of the greatest discoveries in the history of science. So the notion that somehow scientists are resisting it is ludicrous.”

He has been honored by the American Humanist Association twice, in 1982 with the Distinguished Humanist prize and again in 1999 as the Humanist of the Year. In 1990, he was awarded the Royal Swedish Academy of Science’s Crafoord Prize in ecology, considered the field’s highest honor. He died in Massachusetts at age 92. (D. 2021)

PHOTO by Jim Harrison under CC 2.5.

“So I would say that for the sake of human progress, the best thing we could possibly do would be to diminish, to the point of eliminating, religious faiths."

— Interview, New Scientist (Jan. 21, 2015)

Maurice Sendak

On this date in 1928, children’s book illustrator and author Maurice Sendak was born in New York City. Sendak graduated from The Art Students League of New York. His career spanned more than 50 years. He began to illustrate other authors’ books when he was in his 20s. Throughout his career he illustrated more than 75 books and wrote more than 20.

Sendak is best remembered for writing and illustrating Where the Wild Things Are (1963). His other works include In the Night Kitchen (1970), Seven Little Monsters (1977) and Outside Over There (1981). His iconic books and illustrations have spawned movies, stuffed animals and other toys.

He received numerous honors for his work, including the Caldecott Medal (1964, 1974), the Laura Ingalls Wilder Medal (1983), the Hans Christian Andersen Award (1970) and the Astrid Lindgren Award (2003). Sendak’s lifelong partner of 50 years, psychoanalyst Dr. Eugene Glynn, died five years before he did. (D. 2012)

“I’m not unhappy about becoming old. I’m not unhappy about what must be. It makes me cry only when I see my friends go before me and life is emptied. … It’s harder for us nonbelievers.”

— Sendak, interview with Terry Gross, NPR (Sept. 20, 2011)

Nat Hentoff

On this date in 1925, First Amendment devotee Nat Hentoff was born in Boston to Jewish immigrants from Russia. As a freedom fighter who referred to himself as a “Jewish atheist,” he was characterized by a love for rabble-rousing. His New York Times obituary told the story of how Hentoff, as a 12-year-old, sat on his outside porch on a street leading to the synagogue and ate a salami sandwich on Yom Kippur, the Jewish day of atonement and fasting.

In his 1986 memoir Boston Boy, Hentoff said that he had done so to experience what it was like to be an outcast. He wrote that despite infuriating his father and getting sick, he enjoyed it. (“Nat Hentoff, a Writer, a Jazz Critic and Above All a Provocateur, Dies at 91.” The New York Times, Jan. 7, 2017.)

Hentoff attended Boston Latin, a public school, where he read rapaciously and developed an impassioned ear for jazz musicians. While attending Northeastern University, Hentoff became the editor of a student paper. As a journalist he developed an ardent commitment to uphold the First Amendment. After graduating in 1946 and working for several years at a Boston radio station, Hentoff moved to New York in 1953 and covered jazz music for Down Beat until 1957.

In 1958 he started his longtime job as a writer and columnist for The Village Voice, a counterculture weekly, where he remained as a columnist for 50 years. Hentoff also had a flourishing freelance career, contributing to Esquire, Harper’s, Commonweal, The Reporter and the New York Herald Tribune. He wrote for the New Yorker from 1960 to 1986 and for the Washington Post from 1984 to 2000. Hentoff also lectured at schools and colleges and was part of the faculty at New York University and The New School.

Hentoff wrote over 35 books, including The Collected Essays of A. J. Muste (1966), Black Anti-Semitism and Jewish Racism (1970), Blues for Charles Darwin (1982) and Speaking Freely (1997). His writing expressed his left-wing views on issues focal to civil liberties such as censorship, which he ardently opposed, and education reform. He also produced profiles on political and religious leaders, educators and judges. He held some extremely controversial viewpoints, one of which being his stance against abortion.

Hentoff received several awards, including the National Press Foundation’s award for lifetime achievement for contributions to journalism in 1995. In 2004 he became the first nonmusician to receive the honor of being named one of six Jazz Masters by the National Endowment for the Arts. D. 2017.

"This despicable twelve-year-old atheist is waiting to be stoned. Hoping to be stoned. But not hit. I am, you see, protesting a stoning, or so I will say later that day when my father has discovered how his only son has spent the morning of the holiest day of the year disgracing himself and his father."

— Hentoff memoir on eating a salami sandwich on Yom Kippur; "Boston Boy: Growing Up With Jazz and Other Rebellious Passions" (1986)

Saul Bellow

On this date in 1915, writer Saul Bellow was born in Lachine, Quebec, Canada, to Russian immigrants Lescha (née Gordin) and Abraham Bellows. He was raised in a strict Jewish household until age 15, when his mother died. She wanted him to become a rabbi, but he quickly drifted away from religion and began reading a wide variety of literature. Bellow spent most of his early life in Chicago, where he attended the University of Chicago before transferring to Northwestern University for his B.A. in sociology and anthropology.

He later did graduate work in anthropology at the University of Wisconsin-Madison. He’d become a naturalized U.S. citizen in 1941 and served in the merchant marine during World War II. He published his first novel, Dangling Man, in 1944. He taught at the University of Minnesota, University of Puerto Rico and University of Chicago as he worked on his writing career.

Bellow’s early novels include The Adventures of Augie March (1953), which won the National Book Award, Henderson the Rain King (1959) and Seize the Day (1965). He was the first American to receive the International Literacy Prize for his novel Herzog (1964), which spent 42 weeks on the best-seller list. The book is composed of (often unsent) letters of reflection from the protagonist Moses E. Herzog to figures ranging from Nietzsche to President Eisenhower and God. Herzog secured Bellow’s status as an acclaimed author. Mr. Sammler’s Planet (1970) won a National Book Award and Humboldt’s Gift (1975) received the 1976 Pulitzer Prize for Fiction.

After writing numerous works of fiction, Bellow wrote his first nonfiction book, To Jerusalem and Back: A Personal Account (1976), which details his experiences and impressions of visiting Israel for several months in 1975. He received the 1976 Nobel Prize in Literature “for the human understanding and subtle analysis of contemporary culture that are combined in his work.” His final novel, Ravelstein (2000), is a biographical portrait based on Allan Bloom, a political philosopher, author, education critic and personal friend.

During his career he also wrote plays, critically received story collections like Mosby’s Memoirs and contributed fiction to many literary quarterlies. Bellow died at home at age 89 in Brookline, Mass. He was married five times and divorced four times and was survived by three sons and a daughter, the last born in 2000 when he was 84. (D. 2005)

PHOTO: Bellow at Boston University, c. 1992.

“If you asked me if I believed in life after death, I would say I was an agnostic. There are more things between heaven and earth, Horatio, etc.”

— Bellow, New York Times obituary (April 6, 2005)

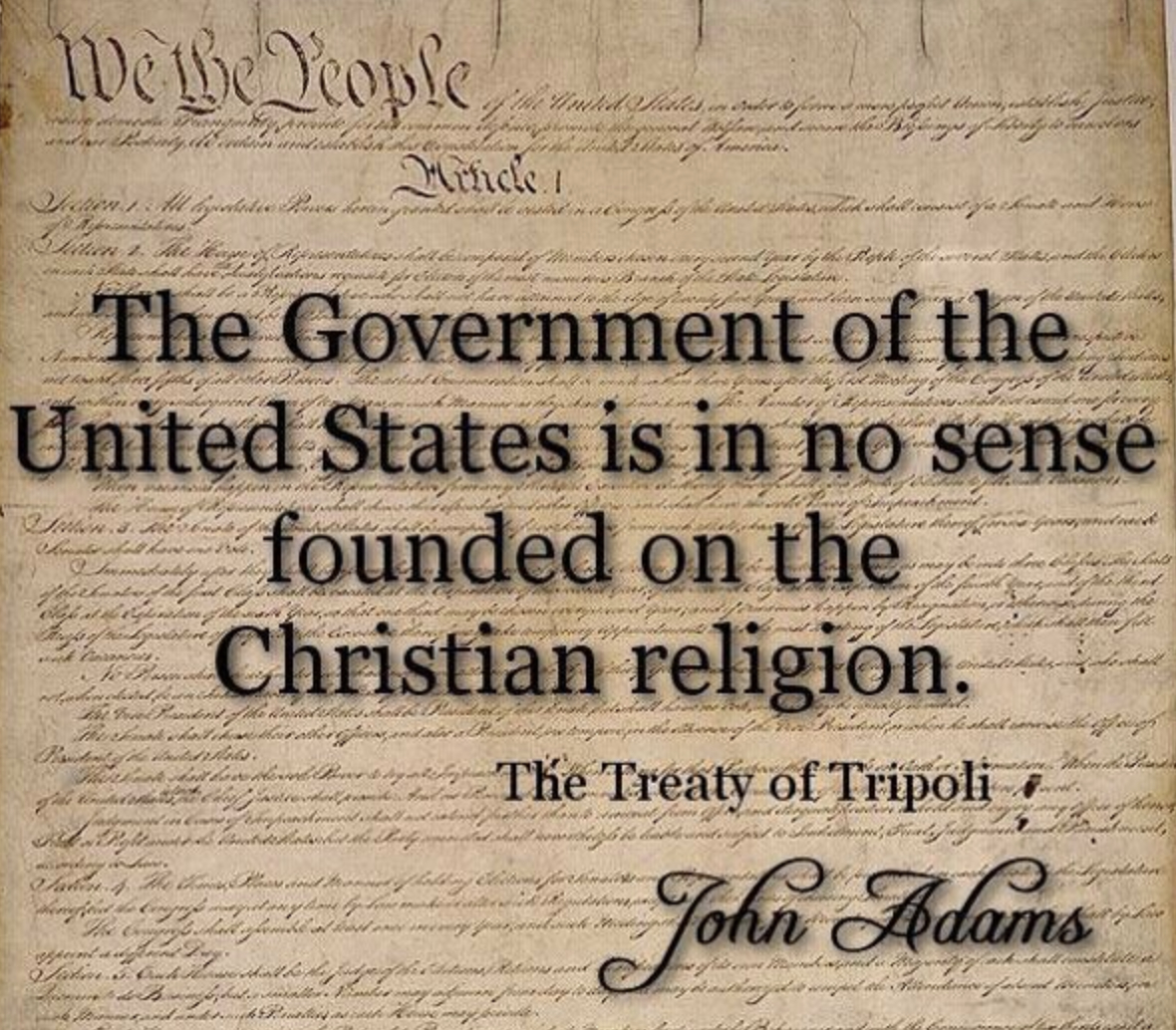

Treaty of Tripoli

On this date in 1797, President John Adams signed the Treaty of Tripoli, which had been unanimously approved by the U.S. Senate on June 7. It secured commercial shipping rights and protected American ships in the Mediterranean Sea from Barbary pirates. The area encompassed what later became the nation of Libya. Joel Barlow negotiated and translated the document for the U.S.

“As the Government of the United States of America is not, in any sense, founded on the Christian religion; as it has in itself no character of enmity against the laws, religion, or tranquility, of Mussulmen; and as the said States never entered into any war or act of hostility against any Mahometan nation, it is declared by the parties that no pretext arising from religious opinions shall ever produce an interruption of the harmony existing between the two countries."

— Article 11, Treaty of Tripoli

Alexandra Lúgaro

On this date in 1981, Alexandra Lúgaro Aponte — attorney, atheist, businesswoman and political activist — was born in San Juan, Puerto Rico, to América (Aponte) and Luis Lúgaro Figueroa.

After graduating from high school at age 15, she earned a degree in business administration from the University of Puerto Rico, followed by a juris doctorate in 2005. While engaged in her law practice, she received a master of laws (LL.M.) in public and private comparative law in 2014 from Complutense University of Madrid. Its thesis: taxation of income derived from illegal activities in Spain, the U.S. and Puerto Rico.

During that period she was also executive director of the Metropolitan New School of America and América Aponte & Associates — the latter founded by her mother — and president of Im-mortalis Corp. Lúgaro’s work focused on educational consulting for nonprofit and government clients. Her mother’s firm had contracts with the U.S. Department of Education for $46 million in funding for various tutorial programs.

Lúgaro gave birth in 2010 to her daughter Valentina through in-vitro fertilization with an anonymous donor. She married professional photographer Edwin Domínguez in Thailand in 2011 and announced their divorce in 2015.

She entered the political arena in 2015 as the first-ever Independent candidate for governor of Puerto Rico. The office traditionally had gone back and forth between the two major parties. Her platform, based on public education and economic development, supported same-sex unions, reproductive choice and legalization of marijuana for medical, social and economic reasons.

A religious group named PR for the Family condemned the platform after Lúgaro came out as an atheist: “You can’t call yourself a Christian and vote for this candidate,” it said in a December 2015 post. (Primera Hora, Nov. 27, 2016) She won just over 11 percent of the vote. In 2020 she ran as the candidate of the Movimiento Victoria Ciudadana (Citizens’ Victory Movement), finished with 14 percent of the vote and announced her retirement from politics.

After the first election, she had started managing reggaeton singer/rapper William Omar Landrón Rivera, aka Don Omar. He retired in 2019 after selling over 70 million albums. She became executive director in 2021 of the Foundation for Puerto Rico’s Center for Strategic Innovation. Motto: There is no future in rebuilding the past.

“I’m a supporter of our constitution, which enshrines the separation of church and state,” she has said. (Latin Post, April 21, 2015) “This is a principle constantly being criticized. But the separation of church and state, I believe, means there should exist, within a democratic state, a way in which we are all treated equally. The separation of church and state prevents the state from meddling in church affairs. In the same way, the church can impose rules on its members but not the rest of society.”

PHOTO: Lúgaro 2016 campaign photo under CC 4.0.

JOURNALIST: Do you attend any church?

LÚGARO: No, not at the moment.

JOURNALIST: Do you believe in God?

LÚGARO: First of all, I think that it is not relevant to the candidacy and I have always said it because I want people to be clear that I am here to represent Catholics, Protestants, Muslims, Buddhists … I have to ensure that all people are equal before the law. However, if you ask me about my personal quality, I don’t believe in God.— Responding to José Santiago Gabrielini of Nueva Isla online. (Primera Hora, Nov. 27, 2016)