February 20

E.B. Foote

On this date in 1829, reformer Edward Bliss Foote was born in Cleveland, Ohio. He was brought up in a conforming Presbyterian household. Foote was a physician with a hand in the newspaper business, publishing the first newspaper in New Britain, Conn. Becoming a Unitarian, then an agnostic, he befriended D.M. Bennett, publisher of The Truth Seeker. Foote was the only foe of the first Comstock bill, which was introduced in the New York legislature in 1872, and passed despite his efforts.

The repressive Comstock Act was soon adopted by Congress, creating censorship of the press through postal regulations. Comstock went after his early foe in 1874, charging Foote with violating postal laws for mailing an educational pamphlet advocating the right of families to limit their size through “contraceptics.” He was fined $3,500 by Judge Benedict of the U.S. Circuit Court of the Southern District of New York in 1876.

Foote helped to organize the National Defense Association seeking repeal of the Comstock laws and aided other Comstock victims. He worked actively within medical societies and at the state legislature to oppose the legitimization of Christian scientists and faith healers. A lifelong advocate of woman’s suffrage, he sent a check of $25 to Susan B. Anthony when she was fined $100 for voting in the 1872 presidential election. He was a member of numerous freethought and professional groups. His son Edward Bond Foote also became a physician and freethinker. (D. 1906)

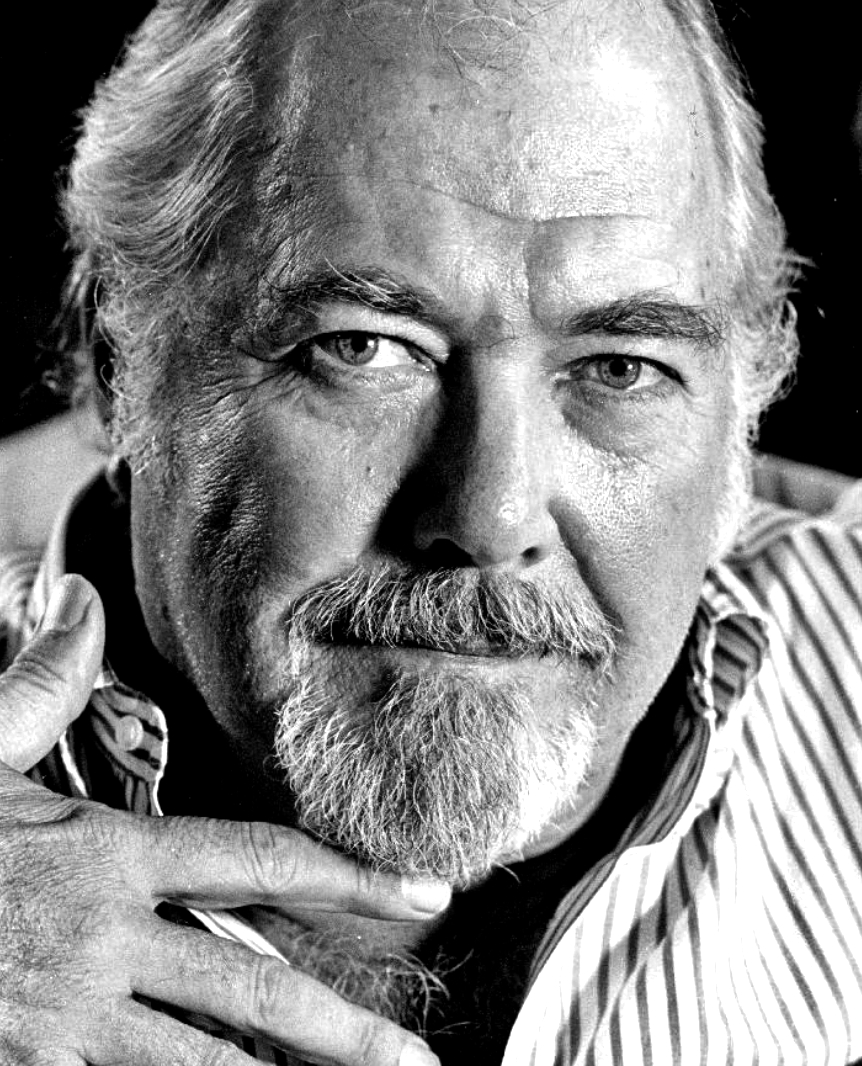

Robert Altman

On this date in 1925, brilliant film director and screenwriter Robert Bernard Altman was born in Kansas City, Mo., into a Catholic family. Altman’s mother, a Christian Scientist who converted to Catholicism, and father, a wealthy insurance salesman, sent their eldest son to Catholic school. He was enrolled at age 16 in military school, and enlisted in the Army Air Force in 1945. Altman co-piloted B-24 bombers in World War II and participated in 46 missions over the Dutch East Indies.

Enthralled by film, Altman moved to Hollywood after his military discharge. He acted in the film “The Secret Life of Walter Mitty” (1947) and co-wrote the screenplay of a film called “Bodyguard” (1948). Struggling for a breakthrough in Hollywood, Altman returned to Kansas City and was hired by a local film company as a writer in 1950.

He began directing short films for the company and made his silver screen directorial debut with “The Delinquents” (1957). That year he returned to Hollywood and began directing the popular television series “Alfred Hitchcock Presents” (1957-58). “MASH” (1970) was his first cinematic success as a Hollywood director.

In his illustrious career as screenwriter, director and producer, Altman was nominated for seven Academy Awards: 1971 Best Director for “MASH,” 1976 Best Director and Best Picture for “Nashville,” 1993 Best Director for “The Player,” 1994 Best Director for “Short Cuts,” and 2002 Best Picture and Best Director for “Gosford Park.” He won a prestigious “Honorary Award” from the Academy in early 2006 for “a career that has repeatedly reinvented the art form and inspired filmmakers and audiences alike.”

Julie Christie, an actress who was directed by Altman in the memorable “McCabe & Mrs. Miller” (1971), noted, “Robert’s cool is part of his belief system. He won’t be bound by rules and he doesn’t expect you to be, either. … And he doesn’t expect people to be sheep” (The Guardian, April 30, 2004). Altman died at age 81 of complications from leukemia. He was survived by Kathryn Reed, his wife of 47 years, their two children and three children from two previous marriages. D. 2006.

“The day he left home [to fight in World War II], he remembers his mother and two sisters putting him on the train with the words, ‘Thank God you’ve got your religion. You’re going to need it now.’ From that day, he says, he never went to Mass again. ‘At home, you had to. Then, when I left the family, I stopped.’ “

— Journalist Suzie Mackenzie, remarking on and quoting Altman in a profile in The Guardian (April 30, 2004)

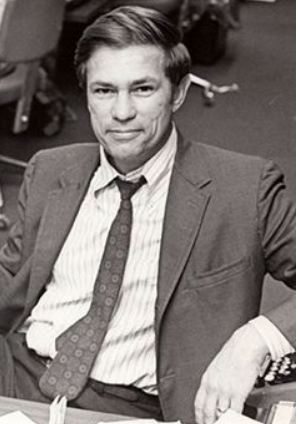

James A. Haught

On this date in 1932, journalist and author James Albert Haught was born in the rural West Virginia town of Reader, which had no electricity or paved streets. His family had gas lights and running water, while most households lived with kerosene lamps and outdoor privies. His parents never attended church, and he ignored religion.

After graduating with a high school class of 13, he worked as an apprentice printer at the Charleston Daily Mail and later was hired in 1953 as a reporter by a rival paper, the Gazette. Republican Gov. Arch Moore Jr. derisively called the Gazette “The Morning Sick Call” in the mid-1970s for its critical reporting on his administration. Moore pleaded guilty in 1990 to five felonies and served 32 months in federal prison for extortion and obstruction of justice.

Haught’s city editor in the 1950s asked him to start going to church on Sunday so he could write a weekly religion column. Despite Haught’s protest that he’d been churchless his entire life, the editor said, “Fine. That will make you objective.” Years on the church beat gradually filled him with distaste for supernatural miracle claims and he felt dishonest mingling with worshipers while not revealing his doubts about gods, devils, heavens, hells, prophecies and other dogma.

His investigative reporting led to several criminal indictments and he won about two dozen newswriting awards. He was named associate editor in 1983 and editor in 1992. When the Gazette and Daily Mail merged in 2015, he assumed the title of editor emeritus while still working full-time on editorials, personal columns and news stories. The only break from daily journalism was as a press aide to U.S. Sen. Robert Byrd for several months in 1959.

In the 1980s he started writing freethought books (12 as of this writing in 2023) and magazine essays. He served as a senior editor of Free Inquiry magazine and writer-in-residence for the United Coalition of Reason and started blogging at Daylight Atheism and Canadian Atheist. Many of his columns ran in Freethought Today and he was an FFRF Life Member.

Haught, who had four children and 12 grandchildren, shied from labels describing the degree of his religious doubt and preferred to be considered as simply an honest person who didn’t claim to know supernatural things that nobody can know. Nancy, his first wife, died in 2008 and he married retired teacher Nancy Lince in 2013. She died in 2021.

He was a longtime member of a Unitarian Universalist congregation. He once debated UU President William Sinkford after Haught observed the national organization turning “more ‘churchy’ and using god-talk. … I proposed that the denomination adopt a statement saying: ‘The UUA takes no position on the existence, or nonexistence, of God. Members are free to reach their own conclusions about this profound question.’ Actually, that statement expresses the UU reality, but leaders were afraid to put it into writing.” (United Coalition of Reason interview, Aug. 23, 2017)

Even at age 90, Haught shrugged off the frailties of age and kept on writing, including a weekly blog for FFRF’s Freethought Now. A column he wrote for his 90th birthday was titled “My Thoughts on Mortality.” He died of cancer at age 91 in hospital hospice in Charleston. (D. 2023)

PHOTO: Haught in the newsroom early in his journalism career of 60-plus years.

“Although billions of people pray to invisible gods, they’re just imaginary, as far as a sincere inquirer can tell. So, to me, the only honest viewpoint is the humanist one, which doubts the supernatural and focuses on improving human life.”

— Haught, "To Question Is the Answer" (July 2007)

Julian Scheer

On this date in 1926, Julian Weisel Scheer, who kept God off a plaque left on the moon in 1969, was born in Richmond, Va., to Hilda (Knopf) and George Scheer. He served in the U.S. Merchant Marine during World War II and after the war entered the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, graduating in 1950 with a degree in journalism and communications.

After working for a decade as a Charlotte News reporter, Scheer started working as a consultant for NASA at the end of the Mercury program in 1962 to create an organizational framework for NASA’s public relations efforts. In early 1963 he became NASA’s assistant administrator for public affairs. He strived to make the public more aware of the program while making flight technicians and astronauts more available for interviews. “The program was really a battle in the Cold War, and Julian Scheer was one of its generals,” astronaut Frank Borman later said. (Washington Post, Sept. 3, 2001)

In preparation for the historic Apollo 11 mission in July 1969 with commander Neil Armstrong, command module pilot Michael Collins and lunar module pilot Edwin “Buzz” Aldrin, Scheer helped craft the message on a plaque that would be attached to a leg of the lunar module’s descent stage, which would land and remain in an area of the moon called the Sea of Tranquility.

Scheer drafted the text for the plaque as a member of NASA’s Committee on Symbolic Activities for the First Lunar Landing. It said: “HERE MEN FROM THE PLANET EARTH FIRST SET FOOT UPON THE MOON. JULY 1969, A.D. WE CAME IN PEACE FOR ALL MANKIND. President Nixon’s and the astronauts’ names and signatures were under the statement.

According to several accounts, including Scheer’s, Nixon wanted God mentioned. Rocket Men: The Epic Story of the First Men on the Moon by Craig Nelson (2009), recounts Scheer telling Nixon aide Peter Flanigan at the White House in early June that not everyone worships the same god after Flanigan tried to insert “under God” after “We came in peace,” with Nixon initialing his approval of the change.

That flew in the face of Scheer’s wish that the plaque should make a universal statement: “Peter [Scheer said], there is no universal god.” Flanigan: “Dammit, Julian, the president wants that change. The president is big on God. … Billy Graham is here nearly every Sunday. The president wants God on the plaque!”

Scheer, in a 1989 column he wrote for the Orlando Sentinel, said NASA administrator Thomas Paine asked him on the way back from the White House what he was going to do. “The plaque has been put on the spacecraft and checked out,” Scheer replied. “I guess the answer is nothing.” Paine answered, “I didn’t hear that.”

William Safire, a speechwriter for Nixon and Vice President Spiro Agnew at the time, later wrote in his New York Times column (July 17, 1989) about reviewing the inscription submitted by NASA: “We left ‘July 1969 A.D.’ intact because it was a shrewd way of sneaking God in [certainly not NASA’s intent]: the use of the initials for anno Domini, ‘in the year of our Lord,’ would tell space travelers eons hence that earthlings in 1969 had a religious bent; piously, we made sure that a Bible with both Testaments was included in the spacecraft’s cargo.” Safire also suggested “came in peace” should replace the original “come” and it was.

About six months earlier, on Dec. 24, 1968, the Apollo 8 crew (Bill Anders, Jim Lovell and Frank Borman) had read verses 1-10 from the Book of Genesis that were broadcast back to Earth while orbiting the moon. Scheer wasn’t involved with writing the text of what the astronauts read (drafted by Borman’s journalist friend Joe Laitin and his wife Christine). Scheer slyly told a Japanese journalist staying at a Houston hotel who was looking for the transcript: “Open the drawer of the table next to your bed. In it you will find a book. Turn to the first page. The words you are looking for are there.” (Chasing the Moon: The People, the Politics, and the Promise That Launched America Into the Space Age by Alan Andres and Robert Stone.) The book was a companion to the 2019 three-episode PBS “American Experience” documentary. The mission’s religious intrusion was later upheld by the 5th Circuit U.S. Court of Appeals, with the Supreme Court declining to take the case.

After the successful Apollo 11 mission, Scheer was awarded NASA’s highest award, the Distinguished Service Medal, and led the crew on tours around the world. He left NASA in 1971 to manage the campaign for Terry Sanford (D-N.C) for the presidency but remained a consultant to the space program and was a trustee of the Smithsonian Institution’s National Air and Space Museum. He worked for a Washington-based communications consulting firm until 1976, when he became a vice president running the Washington offices of LTV Corp., whose holdings include steel mills.He retired from LTV in 1992 and returned to his consulting firm. He wrote several books, including Light of the Captured Moon for children.

He married Virginia Williams and they had three children before divorcing. After his death at age 75 of a heart attack, he was survived by his wife of 36 years, the former Suzann Huggan, with whom he had a daughter. D. 2001.

SCHEER: “What about the people on earth who do not worship our God, Buddhists, Muslims and …”

FLANIGAN: “Damn it, Julian, the president is big on God!”— "What About God/NASA Ignored Nixon's Order" by Julian Scheer, Orlando Sentinel (July 20, 1989)