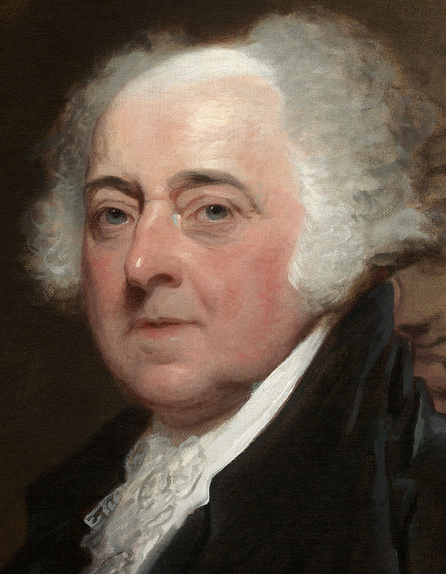

On this date in 1735, John Adams, who became the second U.S. president, was born to John Adams Sr. and Susanna Boylston Adams on a farm in Braintree (now Quincy), Mass. Harvard-educated, he chucked ministerial studies for the law. In his Works, he wrote, “People are not disposed to inquire for piety, integrity, good sense or learning in a young preacher, but for stupidity (for so I must call the pretended sanctity of some absolute dunces), irresistible grace, and original sin.” He married Abigail Smith, who later fruitlessly urged him to “remember the ladies” in the Constitution. Their son, John Quincy Adams, became the sixth U.S. president.

A revolutionary, John Adams opposed the Stamp Act, was a delegate at the First and Second Continental Congresses and proposed George Washington as commander of the military. Adams seconded the motion for the Declaration of Independence. He was also a diplomat. Adams carefully studied religion. According to the biography by his somewhat orthodox grandson, he was “very much in the mold accepted by the Unitarians of New England,” while other historians put him squarely in the deist camp. Later in life he joined the Unitarian Church.

Adams wrote Thomas Jefferson: “Twenty times in the course of my late readings, I have been on the point of breaking out, ‘This would be the best of all worlds if there were no religion in it!’ ” But Adams qualified that by adding, “Without religion, this world would be something not fit to be mentioned in polite company — I mean hell.”

Adams didn’t believe in miracles or prophecies, eternal damnation or demonic possession and wrote a History of the Jesuits as an exposé. In the Massachusetts constitutional conventions of 1779 and 1820, he fought to separate church and state, a reform adopted after his death.

“Although both Jefferson and Adams denied the miracles of the Bible and the divinity of Christ, Adams always retained a respect for the religiosity of people that Jefferson never had; in fact, Jefferson tended in private company to mock religious feelings.” (Friends Divided: John Adams and Thomas Jefferson by Gordon S. Wood, 2017)

Adams believed in an afterlife for emotional reasons. “If I did not believe in a future state, I should believe in no God,” he wrote Jefferson. Adams wrote a three-volume treatise on the U.S. Constitution. He was vice president under Washington from 1788-96 and was elected president in 1796, serving one term. Although he and Jefferson both died on the 50th anniversary of the July 4 adoption of the Declaration of Independence, Adams’ dramatic dying words were “Jefferson lives.” (D. 1826)