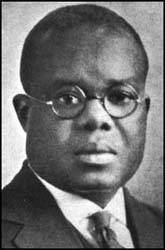

On this date in 1883, Hubert Henry Harrison was born in St. Croix, in the Danish West Indies (now the U.S. Virgin Islands). After his mother’s death, Harrison left the West Indies for New York in 1900, where he earned a high school degree. From 1911 to 1914, he was active in the Socialist Party and, as perhaps its most prominent black member, he founded the Colored Socialist Club. Harrison was active in radical causes, as well as the fight for racial equality.

He eventually left the Socialists due to the movement’s support of segregated local chapters in the South. He formed several black radical groups, the Liberty League in 1917 and the International Colored Unity League in 1924. Harrison’s intellectual influence was widely felt in the Harlem Renaissance in the 1920s, where he was known as the Black Socrates, as well as the father of Harlem radicalism.

Harrison stated that his own doubts about religion were prompted by a reading of Thomas Paine. After he stopped believing in the bible, he was briefly a deist, before finally becoming an agnostic. Though he found Catholic ceremonies attractive and believed in the spiritual part of the human experience, he said in his essay “Paine’s Place” (1911): “I doubt whether I will ever be anything but an honest Agnostic, because I prefer, as I once told you, to go to the grave with my eyes open.” (Quoted in Doubt: A History by Jennifer Michael Hecht, 2003)

“The Negro Conservative: Christianity Still Enslaves the Minds of Those Whose Bodies It Has Long Held Bound,” a 1914 article on atheism, discussed the paradox that African-Americans were largely religious despite the American church’s support for slavery and, later, institutionalized racism. According to Harrison, at the start of the Harlem Renaissance in the early 1920s, atheism, agnosticism and other forms of radicalism were becoming more common in black Harlem.

He died at age 44 in Bellevue Hospital in New York of complications from an appendectomy. (D. 1927)