On this date in 1809, the 16th U.S. president, Abraham Lincoln, was born in Hardin County, Kentucky. Largely self-educated, he worked on farms, splitting those famous rails, and clerking at a store. Lincoln spent eight years in the Illinois Legislature and also rode the circuit of courts for many years. He married Mary Todd; only one of their four sons lived to adulthood. While seeking the nomination for Congress, Lincoln ruefully wrote Martin M. Morris, of Petersburg, Illinois, that “There was the strangest combination of church influence against me .. everywhere contended that no Christian ought to vote for me because I belonged to no Church, [and] was suspected of being a Deist.” (March 26, 1843, Complete Works of Abraham Lincoln, Nicolay & Hay edition.)

Lincoln ran against Stephen A. Douglass for U.S. senator in 1858, losing the election but winning a national reputation. Elected as a Republican as president in 1860, Lincoln guided the nation during the Civil War, issuing the Emancipation Proclamation on Jan. 1, 1863, which freed slaves within the Confederacy. He won reelection in 1864. His wise plans for peace (“With malice toward none; with charity for all”) were foiled by an assassin’s bullet on April 14, 1865, at Ford’s Theatre in Washington, D.C.

Among the words inscribed at the Lincoln Memorial are Lincoln’s Second Inaugural address, which, though full of conventional references to the “Almighty,” astutely observes of the North and the South: “Both read the same Bible and pray to the same God, and each invokes His aid against the other. It may seem strange that any men should dare to ask a just God’s assistance in wringing their bread from the sweat of other men’s faces, but let us judge not, that we be not judged.”

While Lincoln punctuated his eloquent speeches with deistic references to “Divine Providence,” in which he firmly believed, he was strongly rationalist and not conventionally Christian. Among the friends who testified to that was Ward Hill Lamon in Life of Abraham Lincoln (1872). Lamon, who was religious, had known Lincoln for years and wrote: “Perhaps no phrase of his character has been more persistently misrepresented and variously misunderstood than this of his religious belief.”

Lamon related how Lincoln wrote a “little book,” probably an extended essay, to prove “First, that the Bible is not God’s revelation. Second, that Jesus was not the Son of God.” He took the manuscript to Samuel Hill, a shopkeeper and unbeliever, whose son considered the work “infamous.” Hill reportedly snatched the book from Lincoln and threw it into the fire to protect Lincoln’s political career, a story other contemporaries corroborated had been told them.

“But he never told anyone that he accepted Jesus as the Christ,” Lamon noted. His book also quotes Lincoln’s first law partner, John T. Stuart: “Lincoln went further against Christian beliefs and doctrines and principles than any man I ever heard: he shocked me.” David Davis, who knew Lincoln for 20 years and rode with him on the court circuit, told Lamon: “He had no faith, in the Christian sense of the term.” (D. 1865)

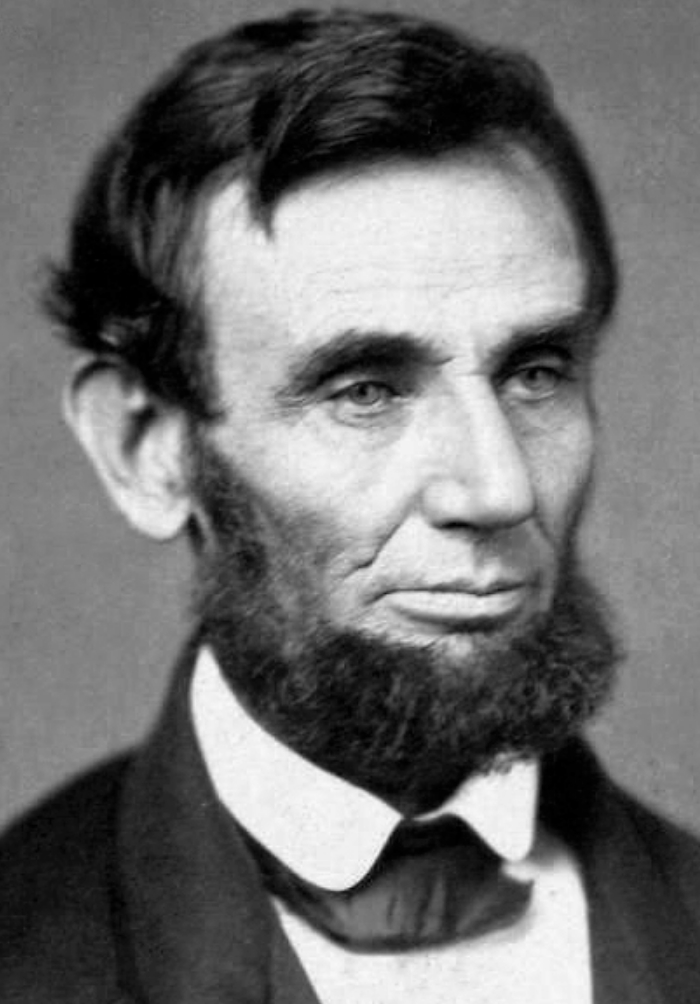

PHOTO: Lincoln on Nov. 8, 1863, 11 days before the Gettysburg Address; photo by Alexander Gardner.