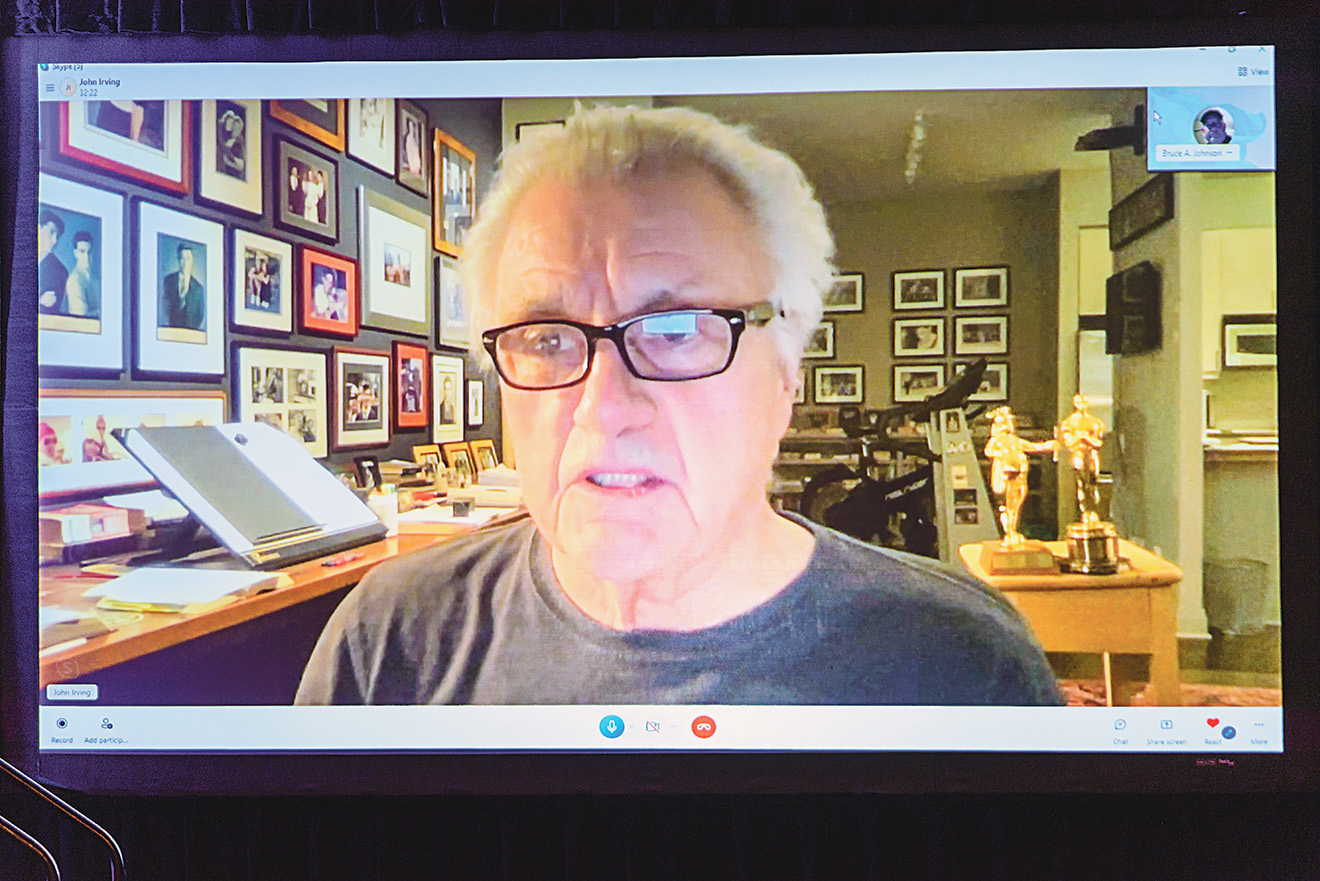

John Irving gave this speech remotely on Oct. 29 during FFRF’s national convention in San Antonio. He was introduced by FFRF Co-President Dan Barker.

Dan Barker: The Freedom from Religion Foundation’s premier award is called the Emperor Has No Clothes Award. This brass statuette is made for us by the company that does the Oscars. It depicts the character in the Hans Christian Andersen story, “The Emperor Has No Clothes.” We immediately offered this award to tonight’s keynote speaker, the distinguished novelist John Irving, after his eloquent guest essay in The New York Times called “The Long Cruel History of the Anti-abortion Crusade” was published June 23, 2019. In that essay, he noted: “We are free to practice the religion of our choice and we are protected from having someone else’s religion practiced on us. Freedom of religion in the United States also means freedom from religion.” And, of course, we at the Freedom From Religion Foundation can say, “amen” to that.

John Irving has written 15 novels, including The World According to Garp, and The Cider House Rules, written in 1999, which has never been a more timely tale of what it was like before Roe v. Wade. He has won the National Book Award, the O. Henry Award and an Oscar for Best Adapted Screenplay of The Cider House Rules.

His all-time best-selling novel is A Prayer for Owen Meany. Almost all the characters in the Irving novels are secular people. His most recent book, his first novel in seven years, has just come out. It’s called The Last Chairlift. It’s a ghost story. It’s a love story. And it depicts a lifetime of sexual politics.

John Irving was scheduled to accept our Emperor award and speak here in San Antonio in 2020. But the pandemic had its own plans. We know that Mr. Irving is just as disappointed as we are that his physician has now advised him not to travel. But we are happy to have him here remotely.

By the way, John Irving is from New Hampshire, but holds dual citizenship in the United States and in Canada. And he’s speaking to us tonight from Toronto. John Irving has received his golden statuette, the Emperor Has No Clothes Award, by mail. Please join me in a very warm welcome for a great novelist, John Irving.

By John Irving

The sexual politics in my novels focus on two different but similar areas — women’s rights and LGBTQ rights. In the 1970s, when I was writing The World According to Garp, I was worried that the extremes of sexual intolerance I was writing about might be passé before the novel was published. Garp is a sexual assassination story: a feminist activist is murdered by a man who hates women; her son is killed by a woman who hates men. A transgender woman is the most compassionate and sympathetic character in the novel.

I needn’t have worried. Sadly, the sexual intolerance I was writing about still isn’t out of date. It should be. When I was just beginning Garp, I remember something my mother said. My mom was a nurse’s aide; she worked in a New Hampshire family-counseling service. Roe v. Wade was relatively new, but the anti-abortion crusaders were already sacralizing the rights of the unborn fetus; the anti-abortion zealots already didn’t care about the rights of the woman who was pregnant.

I was a young, unknown writer with two small children. I had a younger brother and sister — boy-girl twins, who were both gay — and I heard my mother say: “If the men in power imagine they can treat women as if we’re sexual minorities, think of how much worse they’ll treat gay men and women, who are actual sexual minorities!” My mom was right, of course.

In the 1980s, I was writing my sixth novel, The Cider House Rules — a historical novel, purposely set in the time when abortion was illegal and unsafe. I didn’t write a historical novel to be quaint. I wanted to show what that time was like, as a way of saying, “You don’t want to go back to this, do you?” Once again, I was underestimating my birth country’s political backwardness. Cider House was published in 1985.

I live full time in Toronto. In immigration terms, I became a permanent resident of Canada in 2015 and a Canadian citizen in 2019. I made a point of keeping my U.S. citizenship because I intend to continue to vote in my birth country. Officially, I’m a dual citizen of Canada and the United States.

Last summer, I was watching the CBC TV news from Edmonton, Alberta, regarding the visit of Pope Francis, who was asking the forgiveness of Indigenous peoples for the Catholic Church’s role in the history of residential schools in Canada — the separation (and subsequent abuse) of Indigenous children forcibly taken from their families. The pope was in Canada to apologize for Christianity’s role in colonization.

If I’d been in Edmonton, I wouldn’t have been allowed within speaking distance of the Popemobile, but I would like to ask Pope Francis if he has any plans to apologize to a great many nonreligious Americans. I would like to tell Pope Francis that his acolytes on the U.S. Supreme Court have imposed a papal definition of right to life on the rest of us. But why would Pope Francis apologize for this? What’s happened in the United States is what the hierarchy of the Roman Catholic Church and many evangelical churches have long sought — namely, to impose their doctrinal beliefs on all of us.

Of the Republican justices who voted to overturn Roe on the U.S. Supreme Court, only one isn’t Catholic. He’s Episcopalian, but he was born and raised Catholic; his mother, a staunch anti-abortion activist, worked in the Reagan administration. For all intents and purposes, the Republicans on the U.S. Supreme Court were more in step with the Vatican than they were with the First Amendment — the part that says “make no law respecting an establishment of religion.” In overturning Roe v. Wade, Republican justices have made such a law.

The fatwa against the writer Salman Rushdie is a religiously imposed death penalty. Most Americans and Canadians would agree that Iran is an undemocratic theocracy. Is the United States becoming an undemocratic theocracy? A born-again Christian, Ronald Reagan didn’t hesitate to bring God into his conversation about his opposition to a woman’s right to terminate an unwanted pregnancy. “We are a nation of idealists,” President Reagan said in a State of the Union address, “yet today there is a wound in our national conscience. America will never be whole as long as the right to life granted by our Creator is denied to the unborn.”

I wonder if my birth country’s “national conscience” is unaffected by the prospect of young (often underage) women and girls suffering unwanted pregnancies? These are women who may face criminal charges for ordering mail-order abortion pills, or for taking them. Yet more than two-thirds of Americans want to keep Roe; almost 60 percent believe in a woman’s right to an abortion for any reason. Nonetheless, the anti-abortion crusaders have succeeded in their desire to punish women who don’t want (or who lack the means) to become mothers.

In June 2019, I wrote an opinion piece for The New York Times called “The Long, Cruel History of the Anti-Abortion Crusade.” It was, in part, about the history of abortion in the United States — about how women, capable of determining and managing their own reproductive rights, have been undermined by men in power before.

In the time of the Puritans, abortion was allowed until the fetus was “quick” — meaning, when the woman could feel the fetus move. Abortion was permissible beyond the first trimester, up to four or five months.

Our Founding Fathers got this right — the choice to have an abortion or a child belonged to the woman who was pregnant. With the help of midwives, women were having babies and abortions at home since colonial times.

Beginning in the 1840s, and continuing over decades, abortion was outlawed state by state, becoming illegal everywhere in the United States by 1900 — until 1973, when the Roe v. Wade Supreme Court decision held that a woman had a constitutional right to an abortion. For more than two centuries — beginning when the Pilgrims landed in Plymouth, Mass. — abortion was largely permitted. Please remember, abortion was prohibited for scarcely a century. What’s happened now is religious backwardness.

Please remember this, too: We are a nation founded by Separatist Puritans, who were fleeing religious persecution in England. Now the United States has chosen religious persecution. The idea that a fetus is a fully developed person with human rights is a theological concept. This is religious doctrine. This is what post-Roe America represents — namely, somebody else’s religion is being imposed on the rest of us. An undeveloped fetus has more rights than a fully developed woman. Yet once a fetus is fully developed and born, the same people who were so concerned for the fetus don’t care what happens to the unwanted child. What’s more, their foremost interest in the mother is to punish her.

And don’t forget that before the Roe v. Wade Supreme Court decision in 1973, the opposition to abortion wasn’t widely referred to as the right-to-life. Pope Pius XII used the “right to life” term in an “Address to Midwives on the Nature of Their Profession” — a 1951 papal encyclical. Here are Pope Pius XII’s own words: “Every human being, even the child in the womb, has the right to life directly from God and not from his parents, not from any society or human authority.” The poor midwives!

Have you noticed that the same people who sacralize the fetus are generally opposed to any meaningful welfare for unwanted children and unmarried mothers? The prevailing impetus to oppose abortion is to punish the woman who doesn’t want the child. The sacralizing of the fetus is a ploy.

How can “life” be sacred (and begin at six weeks, or at conception) if a child’s life isn’t sacred after it’s born? The Roman Catholic Church, and many evangelical and fundamentalist churches, willfully subject women to mandatory childbirth and motherhood. Procreation is deemed a woman’s primary purpose and function. I’m not overstating! In his 1951 “Address to Midwives,” Pope Pius XII states that “the procreation and upbringing of a new life” is the primary end of marriage.

The end of Roe isn’t the end of King Lear — it’s not as well written — but what Shakespeare has Edgar say rings true. “The weight of this sad time we must obey,/Speak what we feel, not what we ought to say.”

What Dickens wrote about the law should be shoved down the throats of Republican justices on the U.S. Supreme Court: “It is better to suffer a great wrong than to have recourse to the much greater wrong of the law.”

As I read months ago in The Washington Post, a state senator from Oklahoma — Republican Rob Standridge — introduced a bill earlier this year. The bill would permit parents to remove LGBTQ books from school libraries, thus driving gay and trans kids to suicidal loneliness and depression by making these kids feel more isolated than they already feel.

Here’s what Sen. Standridge said: “Christian parents don’t think schools should be evangelizing children into sexual ideologies they don’t agree with.” But with abortion rights, and with LGBTQ rights, it’s the Christians who are doing the evangelizing.

Another state legislator, Republican Rep. Matt Krause of Texas — a San Antonio boy — attended an evangelical college and an evangelical law school. The law school was Liberty, founded by Rev. Jerry Falwell, who once said AIDS was “the wrath of a just God against homosexuals.” Matt Krause proposed legislation banning hundreds of books about abortion and LGBTQ subjects in libraries. My novel The Cider House Rules is among the banned books.

In contrast to Texas, I’m happy to report what’s happening in Ukraine. Brave Olga Nazarova and her Ranok publishing team are back to work. Olga recently sent me the new book jacket for the Ukrainian translation of The Cider House Rules. It doesn’t sound American to say: “Banned in Texas, published in Ukraine.” But that’s how it is in an undemocratic theocracy.

I keep telling this story — I’m tired of telling it — of an unmarried woman or girl who got pregnant. People of my grandparents’ generation used to say: “She is paying the piper.” Meaning, she deserves what she gets — she deserves to give birth to an unwanted child. This cruelty is the abiding truth behind the dishonestly named “right-to-life” movement. “Pro-life” is and always was a marketing term. Whatever the anti-abortion crusaders call themselves, they don’t care what happens to an unwanted child — and they’ve never cared about the mother.

“Freedom from religion” isn’t a marketing term — it’s a necessity. Freedom of religion is a two-way street. Yes, it means that (in a democracy) we are free to practice the religion of our choice. But (in a democracy) it also means that we are protected from having someone else’s religion practiced on us.

Not now — not in these United States.

In December 2016, I began The Last Chairlift, my 15th and longest novel — longer than Bleak House, shorter than David Copperfield (barely). I’ve been trying to imitate Charles Dickens since I was 15, when I read Great Expectations — the novel that made me want to be a novelist. I was 17 when I read Moby Dick. Herman Melville showed me how to foreshadow a novel’s ending. It is the intention of a novel by Charles Dickens to move a reader emotionally — more than to persuade a reader intellectually. These are my intentions, too. And to foreshadow an ending is a theatrical design, intended to set up a dramatic payoff — also to affect a reader emotionally. I write 19th-century, ending-driven novels with realistic characters.

Like The Cider House Rules, The Last Chairlift used to have a metaphorical title.

Cider House was first called “The Boy Who Belonged to St. Cloud’s.” It would have worked. The orphan named Homer will never be adopted — he belongs in the orphanage.

But to title the novel “The Boy Who Belonged to St. Cloud’s” gives too much of the story away. I chose an actual title over a metaphorical one. The rules that are posted in the cider house are real — they’re stupid rules, the migrant apple pickers ignore them (the migrants can’t read them), but they’re actual rules.

The Last Chairlift used to be called “Darkness as a Bride.” It would have worked. The title for Act II of The Last Chairlift is “The Honeymoon on the Cliff.” That would have worked, too. So would the title for Act III — “Rules for Ghosts.” But all these titles are metaphorical. Once again, I chose an actual title over a metaphorical one. The Last Chairlift is real. In the novel, this specific chairlift is called “a hearse — a waiting hearse.”

And, in what I believe is my most ending-driven novel, you don’t even get to this chairlift for 700 pages. Setting up an ending is what my novels do. I think the ending of The Last Chairlift is the best set up.

My foremost political targets in The Last Chairlift — namely, Republicans and the hierarchy of the Roman Catholic Church — have been living up to their questionable reputations. As The New York Times has reported, under Chief Justice Roberts, the U.S. Supreme Court has ruled in favor of religious groups 83 percent of the time.

As Justice Sonia Sotomayor wrote recently, in her dissenting opinion, “This court continues to dismantle the wall of separation between church and state that the Framers sought to build.”

Thank you, Justice Sotomayor. She is the first woman of color on the U.S. Supreme Court — the first Hispanic, and the first Latina. Sotomayor was raised Catholic. She attended Cardinal Spellman High School, a Roman Catholic high school in the Bronx. Sotomayor deserves our thanks. She has not imposed the religious views of her church on the rest of us. She not only understands and respects the separation of church and state, she has most admirably represented that separation.

You may have heard there are ghosts in The Last Chairlift. It is a ghost story and a love story, spanning eight decades of sexual politics. As a nonreligious person, believing in ghosts is as far as I can credibly venture into the spiritual world.

More important than the ghosts — more important to me — there is a good stepfather in The Last Chairlift. All the stepfathers in my novels are good, but this one is the best one. When he’s still a young man, he transitions to female. The good stepfather becomes an outstanding trans woman. Later in the story, there’s an awful crime scene, where this trans woman is called “the only hero.”

My daughter is a trans woman. I’m very proud of her. I wanted to create a trans woman hero for my daughter, Eva, because Eva is my hero. Thank you, Eva.

And thank you, everybody!