Sources, with scans of some of the originals

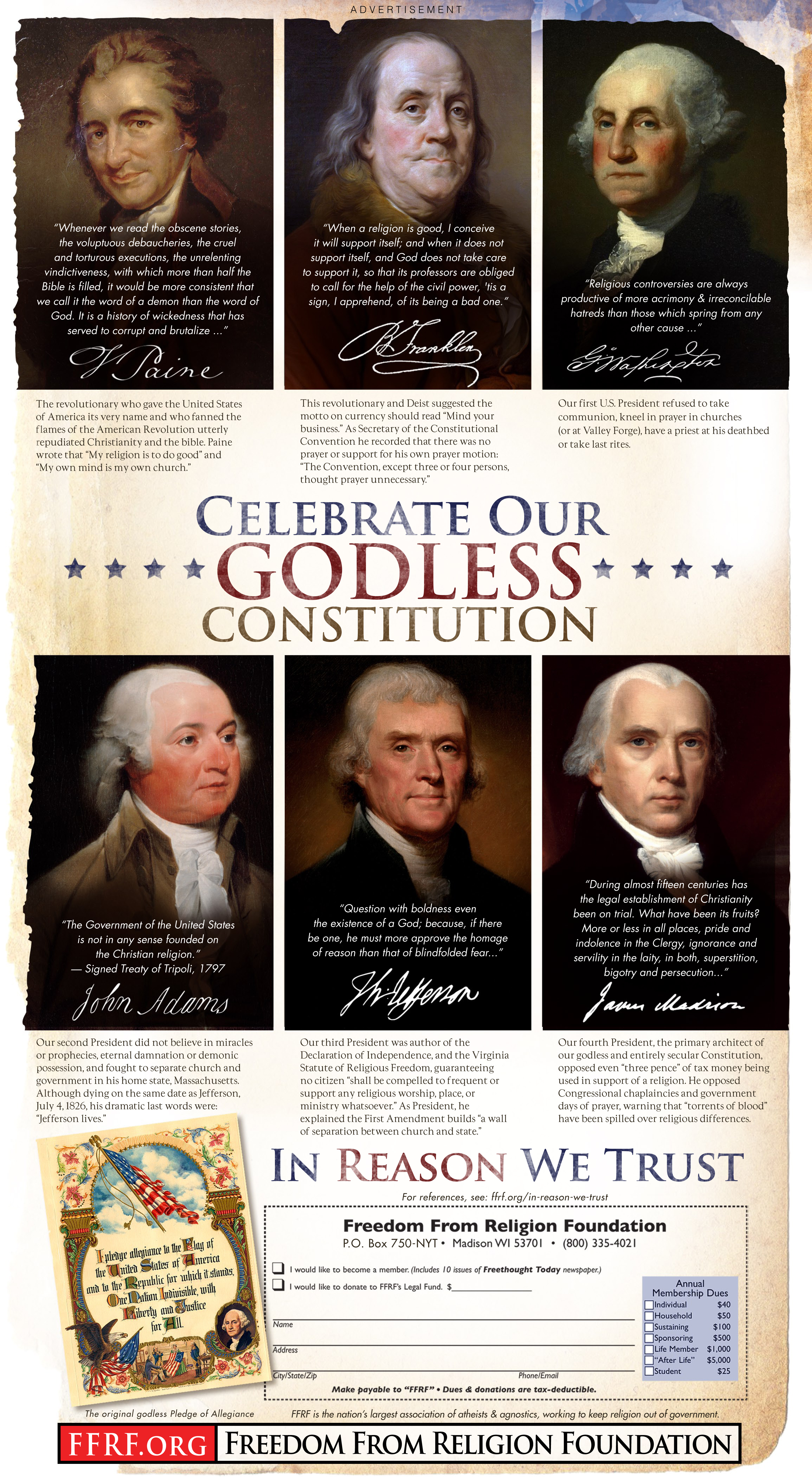

Thomas Paine

“Whenever we read the Obscene stories, the voluptuous debaucheries, the cruel and torturous executions, the unrelenting vindictiveness, with which more than half the Bible is filled, it would be more consistent that we call it the word of a Demon, than the word of God. It is a history of wickedness, that has served to corrupt and brutalize mankind: and, for my own part, I sincerely detest it as I detest everything that is cruel.”

Thomas Paine, The Age of Reason, Part I, (1826 edition) page 13 (first published by R. Carlile, London, 1794) available on Google books.

First recorded use of name, “The United States of America”

Thomas Paine, The American Crisis, no. 2 (January 13, 1777).

“Independence is my happiness, and I view things as they are, without regard to place or person; my country is the world, and my religion is to do good.”

Thomas Paine, Rights of Man, Part 2, page 50 (first published by J. Parsons, London, 1792) available on Google books.

“I do not believe in the creed professed by the Jewish church, by the Roman church, by the Greek church, by the Turkish church, by the Protestant church, nor by any church that I know of. My own mind is my own church.”

Thomas Paine, The Age of Reason, Part I, (1826 edition) page 4 (first published by R. Carlile, London, 1794) available on Google books.

Benjamin Franklin

“When a religion is good, I conceive it will support itself; and when it does not support itself, and God does not take care to support it, so that its professors are oblig’d to call for help of the civil power, ‘tis a sign, I apprehend, of its being a bad one.”

Benjamin Franklin, Letter to Dr. Richard Price, October 9, 1780, in The Private Correspondence of Benjamin Franklin, part I (ed. William Temple Franklin, 2nd ed., Henry Colburn, London 1817) p. 69, available on Google books.

“The Convention, except three or four persons, thought Prayers unnecessary.”

Max Farand, The Records of the Federal Convention of 1787, Volume 1 (Yale University Press, 1911) p. 452, n. 15, available at The Library of Congress.

See original scan of Franklin’s proposal and the notation that prayers are unnecessary.

George Washington

“Religious controversies are always productive of more acrimony & irreconciliable hatreds than those which spring from any other cause . . .”

George Washington, letter to Sir Edward Newenham, June 22, 1792. See a picture of the original letter with language highlighted.

Washington’s refusal to take communion, kneel in prayer, pray at Valley Forge, and have priests and Christian rituals at his deathbed is well-documented. See Ron Chernow, Washington: A Life (Penguin, 2010); Edward G. Lengel, Inventing George Washington (Harper Collins Publishers, 2011); Joseph J. Ellis, His Excellency: George Washington (First Vintage Books Edition, 2005); Brooke Allen, Moral Minority: Our Skeptical Founding Fathers, (Ivan R. Dee Publisher 2006).

GW refused to take communion

On the rare occasions when Washington did attend church, perhaps 12 times a year pre-presidency and only three times in his last three years, he made it a point not to take communion (although Martha did). When asked specifically if Washington was a “communicant of the Protestant Episcopal church,” Bishop William White, who officiated in churches Washington occasionally attended wrote, “truth requires me to say that Gen. Washington never received the communion in the churches of which I am the parochial minister. Mrs. Washington was an habitual communicant.” Bishop William White, letter to Colonel Mercer, Aug. 15, 1835. Other contemporary ministers who personally knew Washington confirm his distaste for cannibalism, symbolic or otherwise. Allen at 31; Lengel at 13; Chernow at 131.

GW did not kneel in prayer

Lengel at 13, 91; Ellis at 45; Chernow at 131.

GW did not pray at Valley Forge

Historians agree that this did not happen. There is no contemporaneous report to verify it and the original report is from The Life of Washington, by Parson Mason Weems, who did not include the story until the 17th edition and also gave us the myth of the cherry tree. See Lengel, 13, 22-23, 76-86; Chernow, 131.

GW did not have a priest at his deathbed or take last rites

There was “. . . missing presence at the deathbed scene: there were no ministers in the room, no prayers uttered, no Christian rituals offering the solace of everlasting life. … He died as a Roman stoic rather than a Christian saint.” Ellis, 269. See also Chernow.

GW did not add “so help me God” to the presidential oath

The oath, laid out in laid out in Article 2, Section 1 of the Constitution, does not contain the religious verbiage and according to Edward Lengel, editor-in-chief of the George Washington papers and over 60 volumes of Washington’s documents, put it: “any attempt to prove that Washington added the words ‘so help me God’ requires mental gymnastics of the sort that would do credit to the finest artist of the flying trapeze.” See Lengel, 105.

In all of Washington’s correspondence, “several thousand letters[,] the name of Jesus Christ never appears, and it is noatbly absent from his last will.”

Gen. A.W. Greely, “Washington’s Domestic and Religious Life,” Ladies’ Home Journal, (April, 1896). See also, Lengel at 13;

John Adams

Treaty of Tripoli, Art. 11 (1797). Negotiated during the George Washington’s presidency, signed by Adams, unanimously approved by the Senate, in American State Papers, Foreign Relations: Vol. 2, page 19: Senate, 5th Cong., 1st sess., 26 May 1797. View the treaty at the Library of Congress.

Thomas Jefferson

“Religion. your reason is now mature enough to examine this object. In the first place, divest yourself of all bias in favor of novelty & singularity of opinion. indulge them in any other subject rather than that of religion. it is too important, & the consequences of error may be too serious. on the other hand, shake off all the fears & servile prejudices, under which weak minds are servilely crouched. fix reason firmly in her seat, and call to her tribunal every fact, every opinion. question with boldness even the existence of a god; because, if there be one, he must more approve the homage of reason, than that of blindfolded fear.”

Thomas Jefferson, letter to Peter Carr (August 10, 1787). See original letter here.

“Believing with you that religion is a matter which lies solely between Man & his God, that he owes account to none other for his faith or his worship, that the legitimate powers of government reach actions only, & not opinions, I contemplate with sovereign reverence that act of the whole American people which declared that their legislature should “make no law respecting an establishment of religion, or prohibiting the free exercise thereof,” thus building a wall of separation between Church & State.”

Thomas Jefferson, letter to the Danbury Baptists (January 1, 1802).

See the original draft, which referred to it as a “wall of eternal separation” here.

James Madison

“During almost fifteen centuries has the legal establishment of Christianity been on trial. What have been its fruits? More or less in all places, pride and indolence in the Clergy, ignorance and servility in the laity, in both, superstition, bigotry and persecution.”

James Madison, Memorial and Remonstrance Against Religious Assessments (1785) ¶ 7.

If you haven’t read this concise masterpiece, please do so now.

Madison opposed chaplainces, government days of prayer:

“Is the appointment of Chaplains to the two Houses of Congress consistent with the Constitution, and with the pure principle of religious freedom? In strictness the answer on both points must be in the negative. The Constitution of the U. S. forbids everything like an establishment of a national religion… The establishment of the chaplainship to Congress is a palpable violation of equal rights, as well as of Constitutional principles.”

Madison was equally critical of presidential and governmental prayer: “Religious proclamations by the Executive recommending thanksgivings & fasts are shoots from the same root… Although recommendations only, they imply a religious agency, making no part of the trust delegated to political rulers. … An advisory Government is a contradiction in terms. The members of a Government as such can in no sense, be regarded as possessing an advisory trust from their Constituents in their religious capacities. In their individual capacities, as distinct from their official station, they might unite in recommendations of any sort whatever, in the same manner as any other individuals might do.”

James Madison, Detached Memoranda (ca. 1817) See the original here.

A three pence tax to support teachers of the Christian religion “will destroy that moderation and harmony which the forbearance of our laws to intermeddle with Religion has produced among its several sects. Torrents of blood have been split in the old world, by vain attempts of the secular arm, to extinguish Religious disscord, by proscribing all difference in Religious opinion. Time has at length revealed the true remedy.”

James Madison, Memorial and Remonstrance Against Religious Assessments (1785) ¶ 11.