A recent headline that should surprise absolutely no one: “Thousands of children abused by members of Portugal’s Catholic Church over 70 years, report finds.” Given the pervasiveness of credible allegations in countries around the world of Catholic clerics molesting children, why would Portugal be any different? It isn’t, of course.

What is surprising is that the report’s numbers are as low as they are: 4,815 cases since 1950. The report, commissioned by the Conferência Episcopal Portuguesa, does however admit that its findings about the numbers of survivors are an “absolute minimum” and only the tip of the iceberg.

The conference is made up of bishops and archbishops of Portugal’s 20 dioceses. Its decisions are subject to approval of the pope in Rome. The country is overwhelmingly Catholic, although fewer than one in five of its professed adherents (almost 90 percent of the 10.2-million population) attend Mass or receive sacraments regularly. For decades it was the state religion.

The bishops chose child psychiatrist Pedro Strecht to lead the independent commission compiling the report. It took testimony from 564 individuals. Other members are psychiatrist Daniel Sampaio, former Minister of Justice Álvaro Laborinho Lúcio, sociologist and researcher Ana Nunes de Almeida, social worker and family therapist Filipa Tavares and filmmaker Catarina Vasconcelos.

Strecht said it would be difficult now to ignore the existence of child sexual abuse and its trauma: “This has taken far too long,” Strecht said, echoing what a survivor told him. “The Church needs to cleanse itself.”

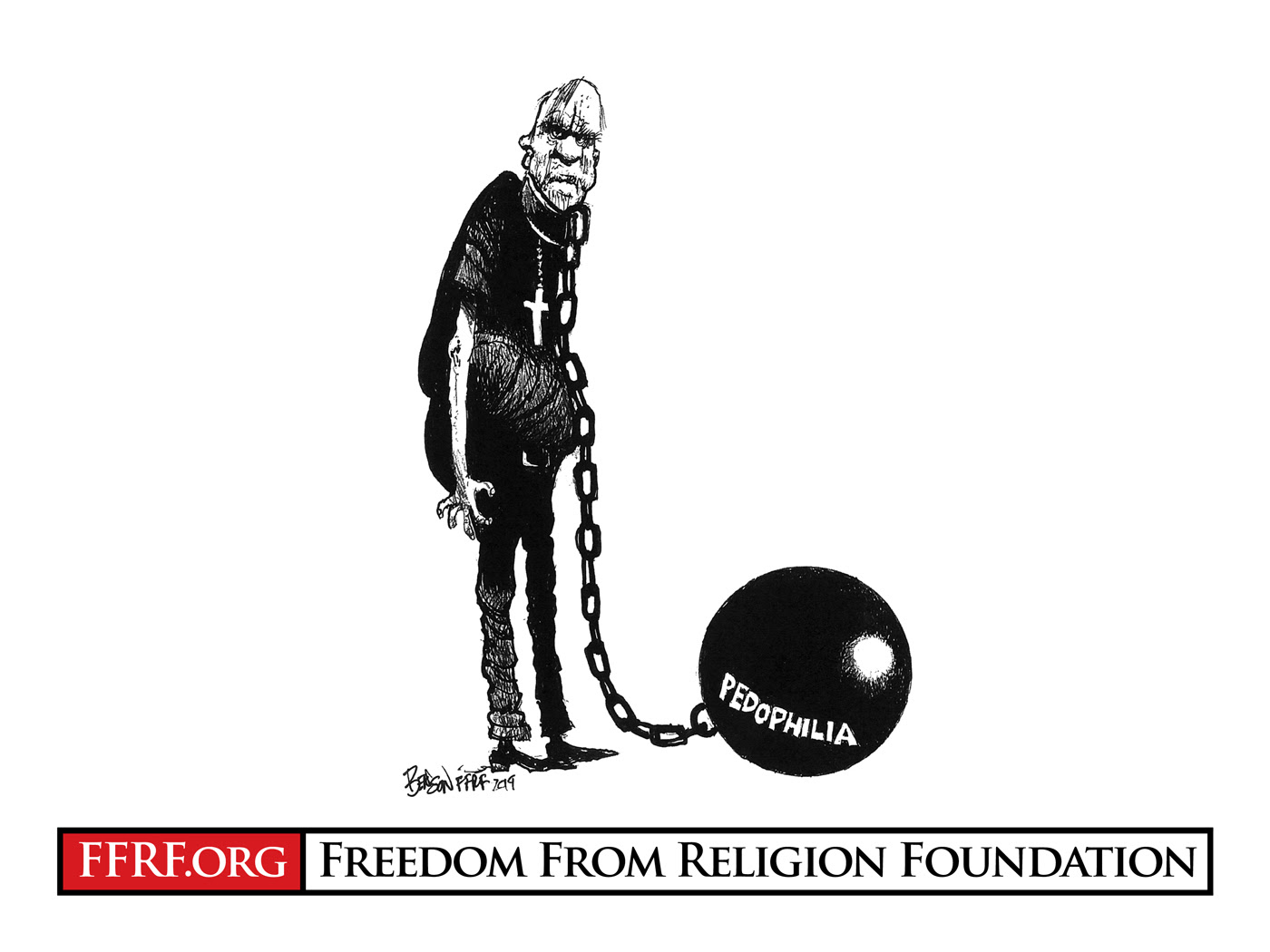

Annie Laurie Gaylor, co-president of the Freedom From Religion Foundation, says she fears that waiting for the Catholic Church to cleanse itself is expecting too much.. “History has shown us time and time again that the church has proven itself incapable of that, so we shouldn’t hold our breath,” she says. FFRF nevertheless supports, however, the work the commission has done to this point.

About three-fourths of alleged perpetrators were priests and most victims were male, the report said. Most abuse took place when children were aged 10-14, with the youngest age only 2. The commission was hampered by the Vatican’s refusal to grant access to church archives until last October. This gave the panel just three months to go through written evidence of abuse. Almost half of those who came forward spoke about their abuse for the first time.

Gaylor criticizes the report’s exclusion from the public of the identities of the accused or locations where the abuse allegedly took place. Bishops are supposed to receive by the end of February a list of people who are accused of abuse and still active in the Church.

The panel recommends that the statute of limitations on such crimes be extended to at least 30 years, from the current 23 years. The Survivors Network of those Abused by Priests wants the threshold to disappear entirely: “Studies have shown that the average age at which a survivor comes forward is 52, and delayed disclosure is a medical fact. … Survivors should be empowered to come forward whenever they are ready and able, and secular law enforcement should be able to act on those reports instead of being time-barred by an arbitrary statute.”

“Alexandra,” 43, told the panel a priest raped her during confession when she was a 17-year-old novice nun. She’s now a mother and kitchen helper. “I kept it secret for many years, but it became more and more difficult to cope with it alone.” She is sickened by the cover-ups. “Bishops asking forgiveness doesn’t mean anything to me. We don’t know if they mean it.”

Clergy abuse has destroyed too many lives — in Portugal and across the planet.

The Freedom From Religion Foundation is a national nonprofit organization with more than 39,000 members and several chapters across the country. It protects the constitutional separation between state and church and educates about nontheism.