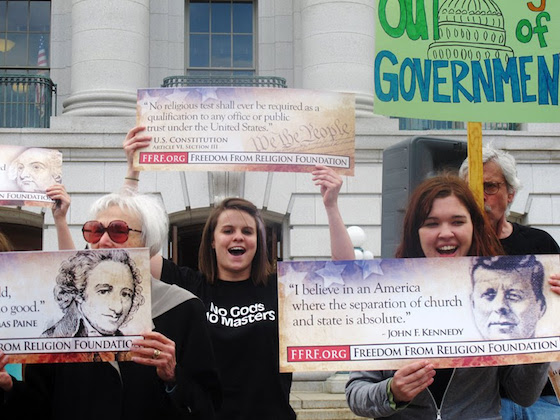

Statement by the Freedom From Religion Foundation

The Freedom From Religion Foundation, on what the government has officially declared to be an annual “National Day of Prayer,” uses this occasion to remind the public of its unconstitutionality.

By a congressional act, now the first Thursday of every May is proclaimed as the National Day of Prayer. This year, the National Day of Prayer Taskforce (which has the appearance of a governmental taskforce, although it is connected with groups such as Focus on the Family) has chosen for its 2018 theme: “Pray for America — UNITY,” based upon a Christian passage in Ephesians 4:3. The taskforce claims Ephesians “challenges us to mobilize unified public prayer for America, ‘Making every effort to keep the unity of the Spirit through the bond of peace.'”

However, if you look at the context of this verse (Paul speaking as a “prisoner for the Lord”), it conveys not unity but the Christian “party line”:

Ephesians 4:1–6: [Paul speaking] “There is one body and one Spirit . . . one Lord, one faith, one baptism; one God and Father of all, who is over all and through all and in all. But each of us was given grace according to the measure of Christ’s gift.”

That is Christian conformity, not unity, a supremely un-American message for public officials to proclaim to citizens of our secular republic.

The best summary of this bad law and why it is unconstitutional is found in the supremely eloquent and beautifully reasoned decision issued by U.S. District Judge Barbara B. Crabb on April 10, 2010, for the Western District of Wisconsin, which agreed with FFRF that the National Day of Prayer is unconstitutional. “The same law that prohibits it from declaring a National Day of Blasphemy” prohibits Congress from declaring a day of prayer, she ruled.

FFRF never fought harder to prove the injury it and its membership have sustained because of the incessant state/church entanglements created by the National Day of Prayer. But an appeals court looking to get rid of this “hot potato” controversy threw our suit out on “standing,” not the merits.

Although some of the order has been changed and some of the legal citations deleted from readability, the words below come directly from an excerpt of Crabb’s historic ruling.

Take a moment not to pray, but to savor a ruling that honors our First Amendment.

Excerpt from FFRF v. Obama

In 1952, evangelist Billy Graham led a six-week religious campaign in Washington,D.C., holding events in the National Guard Armory and on the Capitol steps. The campaign culminated in a speech in which Graham called for a national day of prayer:

Ladies and gentlemen, our Nation was founded upon God, religion and the church . . .

What a thrilling, glorious thing it would be to see the leaders of our country today kneeling before Almighty God in prayer. What a thrill would sweep this country. What renewed hope and courage would grip the Americans at this hour of peril. . .

We have dropped our pilot, the Lord Jesus Christ, and are sailing blindly on without divine chart or compass, hoping somehow to find our desired haven. We have certain leaders who are rank materialists; they do not recognize God nor care for Him; they spend their time in one round of parties after another. The Capital City of our Nation can have a great spiritual awakening, thousands coming to Jesus Christ, but certain leaders have not lifted an eyebrow, nor raised a finger, nor showed the slightest bit of concern.

Ladies and gentlemen, I warn you, if this state of affairs continues, the end of the course is national shipwreck and ruin.

After Graham’s speech, Representative Percy Priest introduced a bill to establish a National Day of Prayer. . . . Absalom Robertson [father of Pat Robertson] introduced the bill in the Senate, stating that it was a measure against “the corrosive forces of communism which seek simultaneously to destroy our democratic way of life and the faith in an Almighty God on which it is based.”

On April 17, 1952, Congress passed Public Law 82- 324:

The President shall set aside and proclaim a suitable day each year, other than a Sunday, as a National Day of Prayer, on which the people of the United States may turn to God in prayer and meditation at churches, in groups, and as individuals.

In 1988, Vonette Bright, founder of the Campus Crusade for Christ, and the National Day of Prayer Committee lobbied Congress to amend the National Day of Prayer statute because Bright “believed that we should have a day in this country where we cover this nation in prayer and the leaders.”

Strom Thurmond introduced the bill in the Senate. He stated that, because the National Day of Prayer has “a date that changes each year, it is difficult for religious groups to give advance notice to the many citizens who would like to make plans for their church and community.

Senator Jesse Helms stated that the bill would allow “Americans . . . to plan and prepare to intercede as a corporate body on behalf of the Nation and its leaders from year to year with certainty.” He believed that “America must return to the spiritual source of her greatness and reclaim her religious heritage. Our prayer should be that—like the Old Testament nation of Israel—Americans would once again ‘humble themselves, and pray, and seek God’s face, and turn from [our] wicked ways’ so that God in heaven will hear and forgive our sins and heal our land.”

On May 5, 1988, Congress approved Public Law 100-307, “setting aside the first Thursday in May as the date on which the National Day of Prayer is celebrated.” On May 9, 1988, President Ronald Reagan signed the bill into law. The current version of the statute provides:

The President shall issue each year a proclamation designating the first Thursday in May as a National Day of Prayer on which the people of the United States may turn to God in prayer and meditation at churches, in groups, and as individuals.

* * *

The role that prayer should play in public life has been a matter of intense debate in this country since its founding. When the Continental Congress met for its inaugural session in September 1774, delegate Thomas Cushing proposed to open the session with a prayer. Delegates John Jay and John Rutledge (two future Chief Justices of the Supreme Court) objected to the proposal on the ground that the Congress was “so divided in religious Sentiments . . . that We could not join in the same Act of Worship.” Eventually, Samuel Adams convinced the other delegates to allow the reading of a psalm the following day.

The debate continued during the Constitutional Convention (which did not include prayer) and the terms of Presidents such as George Washington, Thomas Jefferson and James Madison, each of whom held different views about public prayer under the establishment clause.

This case explores one aspect of the line that separates government sponsored prayer practices that are constitutional from those that are not. Brought under 42 U.S.C. § 1983, the case raises the question whether the statute creating the “National Day of Prayer,” 36 U.S.C. § 119, violates the establishment clause of the United States Constitution. Plaintiff Freedom from Religion Foundation and several of its members contend that the statute is unconstitutional because it endorses prayer and encourages citizens to engage in that particular religious exercise. . . .

In my view of the case law, government involvement in prayer may be consistent with the establishment clause when the government’s conduct serves a significant secular purpose and Unfortunately, § 119 cannot meet that test. It goes beyond mere “acknowledgment” of religion because its sole purpose is to encourage all citizens to engage in prayer, an inherently religious exercise that serves no secular function in this context. In this instance, the government has taken sides on a matter that must be left to individual conscience. “When the government associates one set of religious beliefs with the state and identifies nonadherents as outsiders, it encroaches upon the individual’s decision about whether and

how to worship.”

It bears emphasizing that a conclusion that the establishment clause prohibits the government from endorsing a religious exercise is not a judgment on the value of prayer or the millions of Americans who believe in its power. No one can doubt the important role that prayer plays in the spiritual life of a believer. In the best of times, people may pray as a way of expressing joy and thanks; during times of grief, many find that prayer provides comfort. Others may pray to give praise, seek forgiveness, ask for guidance or find the truth. “And perhaps it is not too much to say that since the beginning of th[e] history [of humans] many people have devoutly believed that ‘More things are wrought by prayer than this world dreams of.'” Engel v. Vitale, 370 U.S. 421, 433 (1962).

However, recognizing the importance of prayer to many people does not mean that the government may enact astatute in support of it, any more than the government may encourage citizens to fast during the month of Ramadan, attend a synagogue, purify themselves in a sweat lodge or practice rune magic. In fact, it is because the nature of prayer is so personal and can have such a powerful effect on a community that the government may not use its authority to try to influence an individual’s decision whether and when to pray.

Accordingly, I conclude that § 119 violates the establishment clause.

* * *