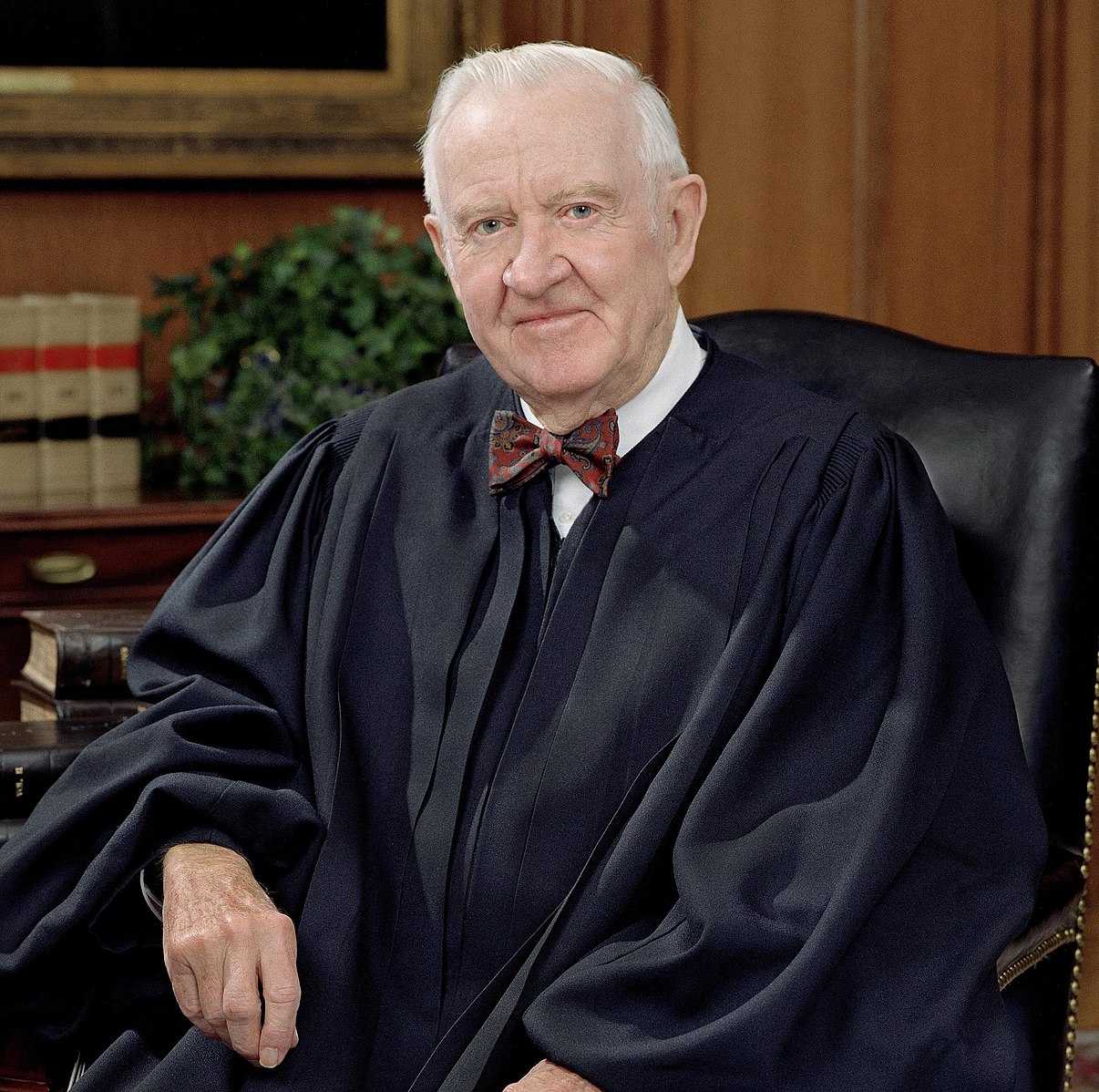

The United States has lost one of the most brilliant and compassionate judges in our nation’s history. The famously empathetic Justice John Paul Stevens, who died just eight months shy of becoming the first 100-year-old former Supreme Court justice, continued to fiercely advocate for individual rights even through his retirement.

Stevens deeply understood the importance of Thomas Jefferson’s wall of separation between church and state. He observed the erosion of this wall in recent decades and wrote powerful dissents when the court lost its way. In 2002, he cautioned: “Whenever we remove a brick from the wall that was designed to separate religion and government, we increase the risk of religious strife and weaken the foundation of our democracy.”

Stevens’ view of state/church separation was true to history, protecting the religious liberty of all Americans. That enlightened view is in serious peril today from justices who don’t understand this issue as well as Stevens did, or who knowingly undermine the secular nature of our government.

For example, the Supreme Court recently held that a massive 40-foot Christian cross on government land did not violate the Establishment Clause. In a prior case involving similar facts, Stevens emphasized that using a cross as a war memorial does a disservice to non-Christian veterans, writing, “The cross is not a universal symbol of sacrifice. It is the symbol of one particular sacrifice, and that sacrifice carries deeply significant meaning for those who adhere to the Christian faith.”

Stevens was famously adept at seeing through government pretext. When considering a school prayer case in 1985 where a public school switched from a recited prayer to a moment of silence specifically “for meditation or voluntary prayer,” Stevens correctly struck the policy down because it was a transparent attempt by the school to continue to promote religion. Stevens called out the government for its religious endorsement, brushing off the school’s attempt at technical compliance.

Devoted to fighting against discrimination in a way that was far ahead of his time, Stevens warned against giving too much deference to government programs that have discriminatory effects. In 1971, he joined the court’s majority in striking down an Oklahoma law that applied differently to men than it did to women. But he disagreed with the court’s decision to give lesser protection to sex-based classification than to other types of discrimination. For Stevens, all disparate governmental treatment “based on an accident of birth” was equally offensive to the U.S. Constitution. As he famously quipped, there is, after all, “only one Equal Protection Clause.”

Stevens’ principled, egalitarian approach to protecting the individual rights of the marginalized is sorely lacking in many of the Supreme Court’s more recent decisions. His compassionate wisdom was a beacon of hope for minorities in America — including the nonreligious — that assured them they could rely on the federal judiciary to safeguard equal justice under the law. The Freedom From Religion Foundation mourns the loss of Justice Stevens and hopes that his substantial legacy will inspire future justices to live up to their title.