May 21

Alexander Pope

On this date in 1688, Alexander Pope was born in England. He was educated in Catholic schools. Pope contracted tuberculosis with the complication of Pott’s disease, or TB of the spine, giving him a hunchback and an adult height of 4 feet, 6 inches. Despite health problems, Pope was a published poet by his teens. He became his generation’s most-respected and popular poet, able to support himself with his writings. A deist and poet of the Enlightenment, his most famous couplet is “Know then thyself, presume not God to scan / The proper study of mankind is man.” (“Essay on Man,” 1733.)

“Essay on Man“ also contains the lines: “For modes of faith let graceless zealots fight / He can’t be wrong whose life is in the right.” Pope also wrote: “Slave to no sect, who takes no private road / But looks through Nature up to Nature’s God.”

Pope’s “Universal Prayer” (excerpt below) was likewise deistic. Pope contributed many immortal phrases, such as “damn with faint praise” (“Satires and Epistles, Prologue to Dr. Arbuthnot”), “a little learning is a dangerous thing” and “To err is human / to forgive divine” from “An Essay on Criticism.” (D. 1744)

“What conscience dictates to be done,

Or warns me not to do,

This teach me more than Hell to shun,

That more than Heaven pursue.”— Pope, "Universal Prayer" (1738)

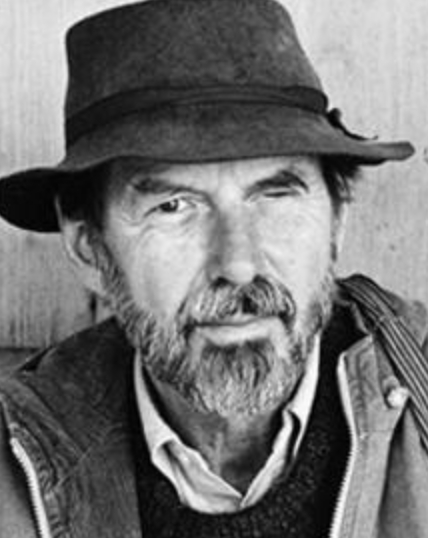

Robert Creeley

On this date in 1926, poet Robert White Creeley was born in Arlington, Mass. His physician father died when Creeley was 4; earlier he had lost his left eye in a car accident. He attended Harvard University from 1943-46 but took time off to serve in the American Field Service as an ambulance driver in Burma and India during World War II.

Creeley returned to Harvard after the war but didn’t graduate. He later received a B.A. from North Carolina’s Black Mountain College and an M.A. from the University of New Mexico. During the 1950s, he taught at Black Mountain (an experimental college that operated from 1933-57) and edited the Black Mountain Review, still recognized as a significant, experimental “little magazine.”

Creeley published over 60 books of poetry, one novel and more than a dozen works of prose, essays and interviews. According to the Poetry Foundation, he transformed American poetry “by being more conversational and emotionally direct” and is credited with formulating the concept that “form is never more than an extension of content.” He taught English and poetics at the State University of New York in Buffalo for over 30 years and lectured academically on poetry at schools around the world.

He married Ann MacKinnon while at Harvard, and in the late 1940s they lived in New Hampshire before moving to France and then the island of Mallorca, where they founded the short-lived Divers Press. Creeley left Black Mountain in 1956 and immersed himself in the poetry renaissance in San Francisco with Allen Ginsberg, Gary Snyder, Kenneth Rexroth and others, while befriending Jack Kerouac.

After divorcing, he moved to New Mexico, where he taught and married Bobbie Louise Hawkins before filling his professorial chair at SUNY-Buffalo. They divorced in 1976 and the next year Creeley married Penelope Highton, a New Zealander. He also served as New York state poet laureate from 1989-91 and was elected a chancellor of the Academy of American Poets in 1999. He died at age 78 of complications of pneumonia while living with Penelope in Marfa, Texas. He had seven children and one stepchild. The Robert Creeley Foundation honors his legacy. (D. 2005)

“I believe in a poetry determined by the language of which it is made. … I look to words, and nothing else, for my own redemption.”

— From Creeley's essay "A Note," Nomad magazine (Winter-Spring 1960)

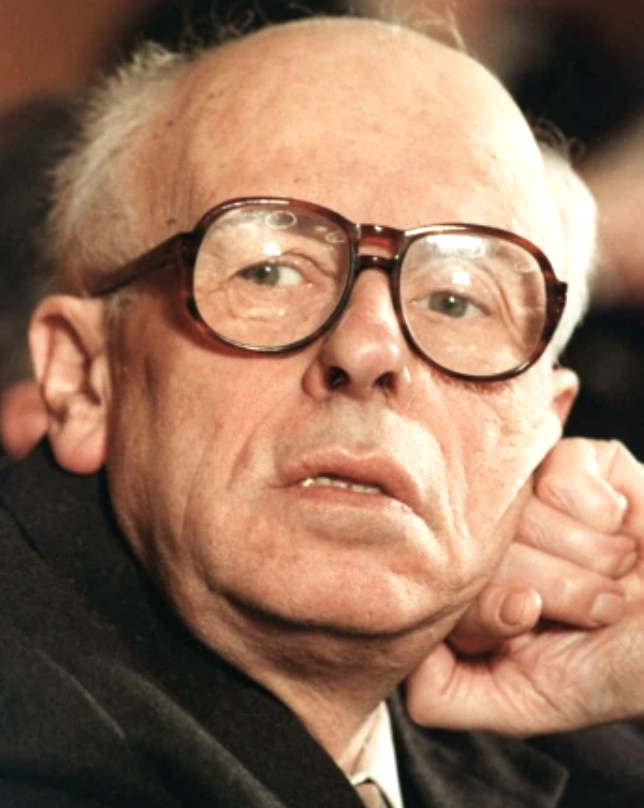

Andrei Sakharov

On this date in 1921, Andrei Dmitrievich Sakharov — nuclear physicist, dissident, Nobel laureate and activist for disarmament and human rights — was born in Moscow to Yekaterina Alekseevna (née Sofiano) and Dmitri Ivanovich Sakharov.

His father was a physics professor and nonbeliever, and his mother and grandmother were religious. The younger Sakahrov decided in his early teens that he was an atheist but believed a “guiding principle” transcended physical laws. (“Andrei Sakharov: The Conscience of Humanity,” 2015)

He studied physics at Moscow State University and after graduating worked in a laboratory in Ulyanovsk. He married Klavdia Alekseyevna Vikhireva in 1943. They raised two daughters and a son. He earned a Ph.D. in 1947. Under the auspices of the Physical Institute of the Soviet Academy of Sciences, he joined a team that built the USSR’s first device, a low-yield uranium bomb detonated in August 1949.

Sakharov played such an integral role in his next project that he became known as the father of the Soviet hydrogen bomb, a design first detonated in 1955. He would later express worry about the effects of radiation, along with deeper concerns: “What most troubles me now is the instability of the balance, the extreme peril of the current situation, the appalling waste of the arms race.” (“New Dictionary of Scientific Biography,” 2008)

He worked on what became the Partial Nuclear Test Ban Treaty signed in Moscow in 1963 by the the U.S., Soviet Union and Britain, banning nuclear weapons tests in the atmosphere, outer space and under water. He returned to fundamental science and began working on particle physics and physical cosmology, including theorizing why the curvature of the universe is relatively small.

He began taking public stances that were politically (and hence physically) risky in a “gulag” state. He opposed scientific academy membership for a proponent of the pseudoscience of Lysenkoism, which denies genetics and well-established agricultural science. The application of Lysenkoism led to the starvation of millions of Russians. Sakharov also opposed the development of an anti-ballistic missile system..

Sakharov married Yelena Bonner in 1972, three years after his first wife died. Bonner, who had a medical background, was a fierce critic of human rights abuses and thus fell under the eye of the KGB along with Sakharov. She was in Italy for medical treatment in 1975 and traveled to Norway to accept his Nobel Peace Prize after he was denied a visa to attend.

The Nobel citation called him “the conscience of mankind” and said he had “fought not only against the abuse of power and violations of human dignity in all its forms, but has in equal vigor fought for the ideal of a state founded on the principle of justice for all.”

After he denounced the 1979 invasion of Afghanistan, he was arrested and banished to Gorky, 250 miles east of Moscow, where he spent seven years in exile. He was named 1980 Humanist of the Year by the American Humanist Association and in 1988 was the recipient of the International Humanist Award by the International Humanist and Ethical Union.

The European Parliament established the Sakharov Prize for Freedom of Thought, to be given annually for outstanding contributions to human rights, in 1985. Biographer Gennady Gorelik called him “a totally nonmilitant atheist with an open heart.”

He died at home in Moscow at age 68 of dilated cardiomyopathy. (D. 1989)

“Like most of the physicists of his generation, he was an atheist. In his later years, this son of a physicist, grandson of a lawyer, and great-grandson of a priest was to come to a new — and free thinking — view of religion. … [He] was simply a humanist for whom it was enough to show his compassion for a fellow man.”

— "The World of Andrei Sakharov: A Russian Physicist's Path to Freedom" by Gennady Gorelik with Antonina Bouis (2005)