July 11

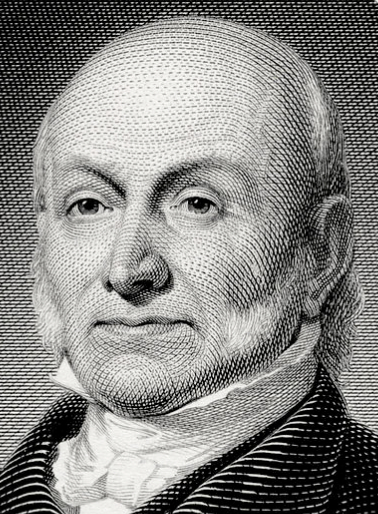

John Quincy Adams

On this date in 1767, John Quincy Adams was born in Massachusetts. He witnessed the Battle of Bunker Hill from above his family’s farm and accompanied his father John Adams (U.S. president 1797-1801) on a mission to France at age 12. Adams studied in France and later at the University of Leyden in Holland. He graduated from Harvard at 26 and began a career as lawyer, professor, writer and diplomat.

He was elected to the Massachusetts Senate in 1802 and became a U.S. senator in 1803. He spent several years as minister to Russia under President James Madison. He was one of the negotiators of peace with England in 1814, then served as minister to England until President James Monroe appointed him secretary of state.

Adams authored the Monroe Doctrine and helped negotiate acquisition of important territories. During his candidacy for president, no candidate — Andrew Jackson, Adams, W.H. Crawford or Henry Clay — received a majority of votes. Although Adams was in second place, the House of Representatives with Clay’s support elected Adams president. As president, he proposed a network of highways, the financing of scientific experiments and the building of an observatory.

He was defeated in 1828 but returned to Congress in 1830 and held his seat until his death in 1848. His distinguished career there, earning him the sobriquet of “Old Man Eloquent,” included his advocacy for the right of petition of abolitionist societies. He battled for eight years and finally succeeded in ending a Southern-imposed gag rule automatically tabling petitions against slavery.

Like his father, he was a Unitarian. He was critical of Sabbatarians and preachers who “rave and rant and talk nonsense for an hour” during sermons. (Diary entry, The Religious Beliefs of our Presidents.) Adams collapsed from a stroke on the floor of the U.S. House at age 80 and died two days later. (D. 1848)

“This young fellow, who was possessed of most violent passions, which he with great difficulty can command, and of unbounded ambition, which he conceals perhaps, even to himself, has been seduced into that bigoted, illiberal system of religion, which, by professing vainly to follow purely the dictates of the Testament, in vain contradicts the whole doctrine of the New Testament, and destroys all the boundaries between good and evil, between right and wrong.”

— J.Q. Adams, diary entry, "Life in a New England Town," 1787-88, cited by Franklin Steiner in "The Religious Beliefs of Our Presidents" (1936)

Mark Fisher

On this date in 1968, writer, theorist and critic Mark Fisher was born in the United Kingdom. Sometimes referred to by his online pseudonym “k-punk,” Fisher was initially known for his blog where he wrote about politics, music and culture. Fisher earned his B.A. in English and philosophy from Hull University in 1989 before completing his Ph.D. at the University of Warwick in 1999. His Ph.D. thesis, “Flatline Constructs: Gothic Materialism and Cybernetic Theory-Fiction” (1999), explored cybernetics and literature.

A co-founder of Zero Books and Repeater Books, Fisher worked as a philosophy and cultural theory lecturer before publishing his most well-known book, Capitalist Realism: Is There No Alternative? (2009). For Fisher, “capitalist realism” is the sense that it is easier for the individual to imagine the end of the world than it would be for him/her to imagine the end of capitalism.

Fisher’s work expands on the work of other philosophers and theorists, including Jacques Derrida, Louis Althusser, Fredric Jameson and others. His book Ghosts of My Life: Writings on Depression, Hauntology, and Lost Futures (2014) popularized Derrida’s concept of “hauntology” — colloquially described as a “pining for a future that never arrived” — by exploring various potential but unachieved futures through cultural sources such as music and film.

Fisher’s The Weird and the Eerie (2017) was published posthumously after his suicide. k-punk: The Collected and Unpublished Writings of Mark Fisher (2004-2016) was published in 2018. (D. 2017)

“The persistence of the fantasy that justice is guaranteed — a religious fantasy — wouldn’t have surprised the great thinkers of modernity. Theorists such as Spinoza, Kant, Nietzsche and Marx argued that atheism was extremely difficult to practice. It’s all very well professing a lack of belief in God, but it’s much harder to give up the habits of thought which assume providence, divine justice and a secure distinction between good and evil.”

— Fisher, New Humanist magazine (Winter 2013)

Pauline McLynn

On this date in 1962, actress and author Pauline McLynn was born in Sligo, Ireland, to Padraig and Sheila McLynn. Six months later they moved to Galway, where she grew up and was educated by the Sisters of Mercy (one of the orders operating the infamous Magdalene Laundries) before enrolling at Trinity College-Dublin to study modern English and the history of art.

McLynn pursued an acting career after graduating and performed with all of the major Irish theater companies. She got her television start on RTÉ, Ireland’s public broadcaster, in the sitcom “Nothing to It?” She’s perhaps best-known for playing the housekeeper Mrs. Doyle on the British comedy “Father Ted,” which aired from 1995-98 and followed the misadventures of three Irish Catholic priests. She was featured in 24 episodes of the series “Shameless,” on which the American Showtime series starring William H. Macy is based.

McLynn won the British Comedy Award for “Top TV Comedy Actress” in 1996 for “Father Ted” and the 2007 Irish Film and Television Award for “Best Actress in a Lead Role in a Feature Film” for the movie “Gypo.” She’s had numerous other TV series and movie roles, including Aunt Aggie in the 1999 film “Angela’s Ashes.” Most recently as of this writing, she played Bunni in 52 episodes of “Drop Dead Weird” on the Australian Seven Network.

Married to theatrical agent Richard Cook since 1997, she has written 10 novels, the first three featuring private detective Leo Street, several short stories and a chapter of Yeats Is Dead, the serial novel by 15 Irish writers, including Frank McCourt.

In the three-part BBC miniseries “Pilgrimage: The Road to Istanbul” (2020), seven celebrities travel from Serbia to Turkey to promote tolerance for all beliefs and cultures. “I was christened a Catholic but I’m a secular person,” McLynn explained on the show, rejecting the notion that religious people have a monopoly on kindness and decency just because of their belief in God. “All of the talking about ‘Well, I like to be kind and everything,’ yeah, I do as well, but I just think that’s being a decent human being.”

“I was brought up an Irish Catholic at a time when the church and the state were so entwined in Ireland that you just didn’t get a choice. It was more a habit than a religion to the point where I realized I wasn’t practicing or anything anymore, it just meant so little that I didn’t even miss it. I’m an atheist.”

— McLynn, quoted in the Irish Mirror (March 22, 2020)

Sally Roesch Wagner

On this date in 1942, Sally Roesch Wagner — historian, author, educator and activist — was born in Aberdeen, S.D., the state’s third-largest city (pop. 25,000) — to conservative Republican parents who were Congregational Church members.

Wagner had a brother and a sister. The family was upper-middle class and socially prominent. Her father, a banker, had German-Russian roots, and her mother’s father served three terms as Aberdeen mayor. “My mom was a brilliant, creative woman who was locked into the impossibility of actualizing herself in the 1950s and suffered as women did during that time. Seeing her caged in that way and seeing the potential that she had when she could escape slightly from it, said to me I will never be that.”

Still, her mother was an engaged parent and headed a statewide Republican women’s group. “She raised me with an egalitarian sense of the worth of human beings without putting price tags on them, which was an incredible gift. I didn’t realize it at the time.” (Veteran Feminists of America interview for Pioneer Histories Project, December 2021)

“My father was the patriarch of the family, and that was the way it was supposed to be. My mother should have been out there doing all kinds of things in the world, and instead she was on Valium. How many women during the ’50s were on Valium?” (Undated interview, Binghamton University Libraries)

Wagner got pregnant at age 17 soon after high school in 1960. At that age in South Dakota and without parental support, abortion was not an option. She married and had another child before long. They had moved in with her husband’s parents in Sacramento, Calif., where she attended Cal State. “I didn’t know about socialism, took a class in economics and realized, oh, my God, I’m a socialist, and my husband was a raging capitalist, and the differences just became greater and greater. He died a couple of years ago, a total Trump supporter, an alcoholic and a non-viable parent, almost from the get go.” They had divorced in 1965. (Ibid., Veteran Feminists)

“Bob Dylan’s ‘Like a Rolling Stone’ got me out of my marriage. That was my support system. ‘Once upon a time, you dress so fine. Threw the bums a dime in your prime, did not you?’ That was my song. This is the song about a white, middle-class married woman leaving her life behind in a moment when getting a divorce was a travesty in my family and among everybody I knew.” (Ibid., Binghamton)

Wagner earned bachelor’s and master’s degrees from Cal State and in 1975 received a doctorate in women’s studies from UC-Santa Cruz. She actively protested against the Vietnam War and on behalf of women’s liberation and was arrested twice for civil disobedience in the early 1980s while dressed up as suffragist Matilda Joslyn Gage. On occasion she also performed as Elizabeth Cady Stanton.

She called the first arrest a “birthing gift” to her grandson Michael, holding his photo while demonstrating at the Seneca Army Depot in New York to protest sending armaments to Europe. The next arrest was on Native American land at a Nevada test site for nuclear weapons. Both charges were eventually dropped but she was strip-searched and handcuffed in detention.

She helped found the women studies’s program at her alma mater Cal State-Sacramento, where she taught for several years before teaching at Mankato State University in Minnesota from 1981-1985. Wagner began work as a visiting professor at Syracuse University in 1997, teaching classes on women’s suffrage and other activist history. She was named Humanist Heroine of the Year by the American Humanist Association in 1992.

She received a National Endowment for the Humanities Fellowship and grant to research Gage. She bought the home Gage lived in from 1854 until her death in 1898 in Fayetteville, N.Y., and in 2002, she turned it into the Matilda Joslyn Gage Museum and Center. “Gage… understood that traditional Christian beliefs have shaped every aspect of women’s lives from the time of Constantine to the present day, and she insisted that they must be challenged directly.” (Feminism and Religion, Nov. 29, 2021)

When asked about priests Daniel and Philip Berrigan, who were brothers and fierce critics of U.S. militarism, Wagner said, “I think [they are] the reason I do not hold the entire Catholic Church in contempt. Examples of how even in an obsolete and corrupt institution, there can be integrity and goodness.” (Ibid., Binghamton)

She died of undisclosed causes in New York at age 82. (D. 2025)

“I became a freethinker — like Matilda Joslyn Gage — at the age of 14, reading books that she had given to her son, knowing nothing about Matilda Joslyn Gage.”

— Interview, Syracuse Woman Magazine (Feb. 27, 2017)