By John Scalise

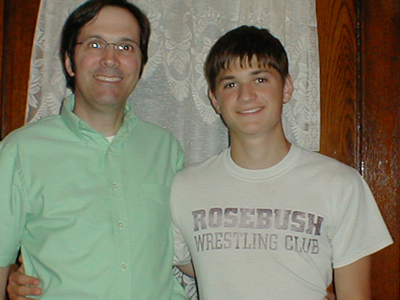

John Scalise and his son, Benjamin, were rejected by Boy Scouts of America because they are not religious.

|

It seemed self-evident to me that our public school would not want to sponsor an organization that discriminated against children based on their family’s religion, or lack thereof. I was wrong. When the U.S. Supreme Court refused to hear our appeal this past May, they effectively agreed that religious-based discrimination in public schools is perfectly fine, if the people being discriminated against are humanists and freethinkers.

Our story began in 1997, when my son, Ben, then a third grader, came home from school with a flyer he received from his teacher inviting him to join the Cub Scouts at an organizational meeting being held at the school that evening. I had been a Cub Scout myself when I was Ben’s age, and I had enjoyed the experience a great deal. I thought that being a Cub Scout would also be a great experience for him. The meeting was designed to demonstrate many of the cool things that one can do as a Cub Scout, and Ben was excited to join. When no one volunteered to be the leader of Ben’s third-grade den, the troop leader asked me if I would do it. I said yes. I then commenced filling out the pile of forms required of applicants for leadership positions in the Boy Scouts of America (BSA).

When we returned home, I re-read the forms I was given, and realized that one of them contained the BSA’s “Declaration of Religious Principles” (DRP). The DRP says, in part, “no member can grow into the best kind of citizen without recognizing an obligation to God.” I contacted the BSA regional office and asked that they exempt me from signing the DRP, as I could not do so in good conscience. I explained that I was still interested in being a den leader, and Ben still wanted to be a Cub Scout. Within a few short weeks, Ben and I were formally expelled from the Cub Scouts because of my refusal to sign the DRP and affirm a belief in God. Ben was very disappointed.

I wrote the school board about the situation and asked that they no longer let the BSA recruit boys through the elementary schools. The superintendent reviewed the situation and determined that, despite the religious discrimination, the BSA was a good program for boys and he was unwilling to discontinue their recruitment practices in the elementary schools. He did agree to my request for a disclaimer on BSA literature distributed by the schools that would indicate that the BSA discriminated on the basis of religion, and that it was not in any way affiliated with the school district. While not what I had hoped for, I accepted this resolution.

The next year and a half went by without any BSA recruitments being held at my son’s elementary school. Then, in May 1999, a BSA recruiter went into my son’s fourth grade class during instructional time, and invited “all” of the boys in the class to become Cub Scouts. He described all of the fun things Cub Scouts do, and encouraged them to join. When my son raised his hand and asked if the Scouts would now let him join even though his family did not believe in God, the recruiter humiliated him in front of his classmates.

Following the recruiter’s visit, Ben was harassed and assaulted by some of the other children at his school because of our family’s beliefs. Additionally, the flyers that were passed out to the students bore no disclaimer as the superintendent had promised. I contacted the superintendent again and demanded that the BSA no longer be allowed access to my son via his school, but my concerns were ignored. Later that year the BSA was back in my son’s school, this time with the portion of the DRP that says students who do not believe in God cannot be good citizens printed on the back of their flyers. This was supposed to be the disclaimer for which I had asked.

In June 2000, the Dale decision came down from the U.S. Supreme Court. This decision settled the question of whether the BSA was a public or private organization. The Supreme Court ruled that it is a private religious organization and that it can set its own criteria for membership. This decision led me to file a formal complaint with the school district alleging that the district was allowing a private religious organization to recruit children during school hours. The superintendent was the final arbiter of this complaint and he decided that while he would stop the recruiters from entering the classrooms during class time, he would not stop the district’s partnership with the BSA and would continue to allow them to recruit in the schools via other means. Dissatisfied with this outcome, I contacted a freethinking attorney friend, Timothy Taylor, and asked for his assistance. Tim reviewed the evidence and the applicable law and advised me that a letter from him to the superintendent outlining the law and district policy should convince him to change the practice of partnering with BSA. The superintendent ignored the letter.

Entering into a lawsuit was not an easy decision for my family and me. I knew there would be repercussions in the community, as I was an elected member of our city commission, and Ben had already been harassed and assaulted by peers. The only other issue was cost. Tim offered to do the legal work pro bono, but I would have to pay all of the other costs, which could amount to several thousand dollars if we had to appeal. After discussing the pros and cons with my children and my wife, Lynn, we decided to proceed.

The law in Michigan is very clear; religious discrimination of any kind is not allowed in public schools, and fraternities of the kind created by the BSA are not allowed to operate within the schools. Additionally, private organizations that are exempt from the public accommodations act lose their exemption if they operate in concert with another organization that is a public accommodation, like the schools.

Nationally, the BSA uses charter agreements to partner with local organizations that in turn sponsor the Cub Scout troops. Organizations that sponsor a troop must agree to uphold the tenets of scouting, including the “Declaration of Religious Principles.” Through the discovery process, we learned that the public schools in our district had been sponsoring troops for at least the past decade, and likely much longer, and that they intended to do so in the future. The district had officially listed Scouts in its policy manual as a “school-related activity,” and provided free use of the school facilities, whereas other groups needed to pay rent. The school principals sponsored some of the troops, while the schools’ Parent Teacher Associations sponsored others. Each school allowed the Scouts to recruit during the school day, and one school even had a permanent display case devoted to the Cub Scouts in its main hallway. The law and the evidence led Tim and me to believe that this was going to be an open-and-shut case, and that we would win quickly and decisively. The BSA and the schools chose to be represented by the same law firm. Their basic argument was that the BSA was simply using the schools facilities, like other similar groups, and that we were trying to quash their right to free speech and assembly.

The case was argued in early 2001. In December of that year the court decided that our evidence was not sufficient to prove that the schools were sponsoring the BSA, but the judge did acknowledge that Ben’s constitutional rights under the Michigan and U.S. Constitution were violated when the recruiter came into the classroom during class time. The judge, however, neglected to provide a remedy or relief to us. He did not enjoin the district from further recruitment, and he did not cite any statute that would allow us to pursue damages. We filed a motion to clarify the decision and asked for a specific remedy, but upon reconsideration nearly a year later, the judge dismissed the case entirely, leaving us right back where we started.

We decided to appeal the case to the Michigan Court of Appeals, believing that the evidence for school sponsorship was compelling, and that the lower court’s decisions were contradictory and nonsensical. As soon as we drew our appeals panel, we knew we were in trouble, as all three were conservative religious ideologues who trumpeted their beliefs to anyone who would listen. One was a Bush nominee to the federal bench, stuck in the Senate because of his extreme views. We were pleasantly surprised during the oral arguments, however, when they pressed the school district’s attorney to show how allowing the BSA into schools was any different than allowing the Ku Klux Klan into schools. We thought that maybe the justices would set aside their ideology and rule on the facts . . . not. Nearly a year later, the decision came down and we lost on every count. Not only did they rule that the schools were not sponsoring the BSA, they ignored all of the laws that applied. They went so far as to accuse me in the written opinion of being “hostile to even a scintilla of religion in the public schools.”

At this point I was mad, and appealing the case to the Michigan Supreme Court was a no-brainer. While Tim was preparing the brief, I researched the justices on the court and discovered that one was on the board of his regional Boy Scout Council. The Chief Justice additionally listed his work with the BSA as his only community service activity in his press releases and on his web page. It seemed to me that these two characters would be biased about the case and should recuse themselves. Tim agreed, and along with the appeal, we asked that the two not be a part of the decision to hear the case.

After several months of waiting, the court refused our appeal. Of the two justices that we asked to recuse themselves, one did, but the other, the Chief Justice, did not. This failure to not recuse and provide an explanation so angered one of the justices that she wrote a lengthy opinion as to why it was unconstitutional for the Chief Justice to behave in this way. She refused to participate in the case until the justices clarified this issue. The result was that there were then only two justices who voted to hear the case. Had both justices recused themselves, the appeal would likely have been accepted. We filed a motion to reconsider the decision based on the constitutional issues raised in the dissent, but again we were turned away.

Having exhausted all of our remedies in Michigan, this left but one other option, the U.S. Supreme Court. We knew that an appeal to the U.S. Supreme Court was a long shot at best, but it was a chance we felt we needed to take. Financially, I had exhausted my resources for the case, and could not come up with the funds to proceed. It was at this point that the Freedom From Religion Foundation stepped up to the plate and agreed to pay the filing fees and provide support to appeal to the Supreme Court.

In reply to our petition to the Supreme Court, the BSA and school district said that our case was frivolous, and that we had never argued federal questions before. We pointed out that they had raised the federal questions at every level, and that each court opinion relied on the federal constitutional rights of BSA. Despite all of our arguments, the Supreme Court denied our petition. The case was over.

From the beginning to the end, our fight to stop the BSA from discriminating in our public schools took nine years. While we lost the case, I do not regret having fought this fight. As a result of our lawsuit, my local school district no longer enters into charter-partnership agreements with the BSA, and nationally the BSA has been actively moving away from public school sponsorship of troops. As with most battles to end discrimination, I believe that time is on our side. Whether we win or lose in courts, with each lawsuit more people become aware that the BSA discriminates against little children simply because their parents are freethinkers. In time, this will be unacceptable to enough people that more sweeping changes will occur. In the meantime, it is essential that freethinkers come out of the closet. When our friends, families and neighbors know that we are freethinkers, it will be much harder to accept the kind of discrimination practiced by the Boy Scouts of America.

John Scalise is a Michigan member of the Freedom From Religion Foundation. He is a psychologist who works with a local community mental health center and is married to a psychologist. They have four teenagers. He is president and co-founder of the Great Lakes Humanist Society, a freethought group in central Michigan. He is also the president of the Central Michigan Branch of the ACLU of Michigan, and sits on the state board of directors as a vice president.