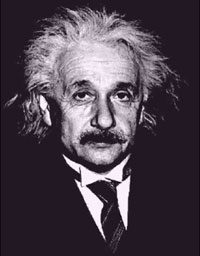

Navy ensign and Einstein

correspondent Guy H. Raner |

By Guy H. Raner

On account of his renown and the nature of his contributions, Albert Einstein was asked about his personal religious views on many occasions. Though he appears not to have been reticent about the question, his responses were usually couched in broad or metaphoric terms susceptible to ambiguous interpretation. 1 Moreover, he often framed aphorisms in religious language. 2 Finally, the popular press, notably the Hearst Sunday newspapers, often published distorted accounts attributing conventional pietism to Einstein. I present here abridged versions of two letters I wrote to Einstein in 1945 and 1949, together with Einstein’s brief, lucid responses. While completely consistent with Einstein’s more complex statements, the responses are, to the best of my knowledge, the most explicit that Einstein ever wrote on the subject.

I first wrote to Einstein on June 10, 1945, when I was a Navy ensign en route to the western Pacific to join my ship. I was on a merchant ship headed to Guam, where I was to board a Kaiser class carrier named the USS Bougainville as its Communications Officer. My letter said, in part:

I had quite a discussion last night with a Jesuit-educated Catholic officer . . . [in] which he made certain statements regarding you which I tend to doubt. To clear my mind on the subject I would appreciate it a great deal if you would comment on the following points:He said that you were once an atheist. Then, said he, you talked with a Jesuit priest who gave you three syllogisms which you were unable to disprove; as a result of that you became a believer in a supreme intellect which governs the universe. The syllogisms were: A design demands a designer; The universe is a design; therefore, there must have been a designer. On that point I questioned the universe being a design; [laws of nature account for observed natural phenomena and the vastness of the universe for its complexity]. Anyway, he said that was enough to convince you of the existence of a supreme governor of the universe. Point two was: “Laws” of nature . . . exist; if yo have a law you must have a law giver; the law-giver was God. Sounds like an exercise in semantics to me. . .

He could not remember the third syllogism; however if the story is accurate you probably do. . . . I would greatly appreciate a short letter clarifying the situation. . .

Albert Einstein

|

Einstein responded very promptly from a summer vacation place, Knollwood on Saranac Lake. His air-mailed response dated July 2nd, 1945, was typed by him, using a portable typewriter, on stationery embossed with a seal. As I had requested, he also sent a carbon copy to my interlocutor. The main test of Enstein’s letter follows:

Dear Mr. Raner:I received your letter of June 10th. I have never talked to a Jesuit priest in my life and I am astonished by the audacity to tell such lies about me.

From the viewpoint of a Jesuit priest I am, of course, and have always been an atheist. Your counter-arguments seem to me very correct and could hardly be better formulated. It is always misleading to use anthropomorphical3 concepts in dealing with things outside the human sphere–childish analogies. We have to admire in humility the beautiful harmony of the structure of the world–as far as we can grasp it. And that is all.

With best wishes,

yours sincerely,

/s/ A. Einstein.

Albert Einstein

Four years later, on September 25, 1949, I wrote again:

Dear Dr. Einstein:[The letter begins with a recapitulation of the prior correspondence.] I considered your letter . . . strictly personal . . . and have never permitted any of it to get into any publication, although I have showed it to a few personal friends. Last summer, [a classmate in a historiography seminar at the University of South California] remarked that such a letter is of historical value, and that I should get your permission to publish it at some future date . . . Have you any objection to its future publication, if an occasion should arise making publication possible.

[In your letter,] You say that “From the viewpoint of a Jesuit priest I am, and have always been, an atheist.” Some people might interpret that to mean that to a Jesuit priest, anyone not a Roman Catholic is an atheist, and that you are in fact an orthodox Jew, or a Deist, or something else. Did you mean to leave room for such an interpretation, or are you from the viewpoint of the dictionary an atheist; i.e., “one who disbelieves in the existence of a God, or Supreme Being”? . . . . . . polls taken in high schools have indicated that about 95% of the students held orthodox religious opinions, reflecting . . . general opinion, which indicated a long, uphill climb before the mists of superstition give way to a more humanistic outlook.

Einstein’s reponse, again typed by him, is dated September 28, 1949, so he must have responded almost immediately upon receiving my inquiry. It says:

Dear Mr. Raner:I see with pleasure from your letter of the 25th that your convictions are near to my own. Trusting your sound judgment I authorize you to use my letter of July 1945 in any way you see fit.

I have repeatedly said that in my opinion the idea of a personal God is a childlike one. You may call me an agnostic, but I do not share the crusading spirit of the professional atheist whose fervor is mostly due to a painful act of liberation from the fetters of religious indoctrination received in youth. 4 I prefer an attitude of humility corresponding to the weakness of our intellectual understanding of nature and of our own being.

Sincerely yours,

/s/ A. Einstein.

Albert Einstein.

For many years I made no attempt to publish these letters, possibly because I was a teacher in the Los Angeles public schools and saw no reason for directing public attention toward myself. Now that I have retired, I feel free to make them available. 5

Notes:

1 Best known is his cablegram to the New York Times: “I believe in Spinoza’s God who reveals Himself in the orderly harmony of what exists, not in a God who concerns himself with fates and actions of human beings.” 25 April 1919, p. 60, col. 4. Quoted in Albert Einstein, Philosopher-Scientist, Paul Arthur Schilpp, ed., Library of Living Philosophers, Evanston, IL, 1949, pp. 660-1.

2 The most widely quoted are “Der liebe Gott wrfelt nicht” (God doesn’t play dice”) and “Raffiniert is der Herrgott, aber boshaft ist er nicht” (“Subtle is the Lord God, but malicious he is not.”) See, inter alia, A. Pais, Subtle is the Lord . . ., Oxford University Press, New York, 1982.

3 Here Einstein covered the typographical error “antro” with x’es, and overtyped an “a” which he had mistyped for the third “o” in anthropomorphical.”

4 Einstein hand-wrote an “o” over the “p” he had mistyped in “yputh”.

5 Note by L.S.L.: Einstein’s remarks in these letters are entirely consistent with a 1980 conversation that my colleague Professor Arthur Wayman and I had on the subject of Einstein’s religious views with the late Professor Ernst Straus, a mathematician who had been Einstein’s assistant from 1944 to 1948.

Guy H. Raner is a Foundation member. He acknowledges the assistance of Foundation member Lawrence S. Lerner, Department of Physics & Astronomy, California State University, Long Beach.

He graduated from the University of Missouri in 1942, earned a secondary teaching credential in 1946 from the University of California at Los Angeles, and a Master’s in political science in 1956.

He was recalled to active duty in the Korean War, 1951-52.

He began teaching U.S. government and history in 1946, and became chair of the department of social studies.