By Catherine Fahringer

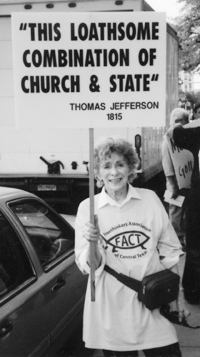

Catherine Fahringer picketing the National Day of Prayer event on the steps of City Hall in San Antonio with many other protesters

|

“And when thou prayest, thou shalt not be as the hypocrites are: for they love to pray standing in the synagogues and in the corners of the streets, that they may be seen of men. Verily I say unto you, they have their reward. But thou, when thou prayest, enter into thy closet, and when thou hast shut the door, pray to thy Father which is in secret; and thy Father which seeth in secret shall reward thee openly. But when ye pray, use not vain repetitions, as the heathen do; for they think they shall be heard for their much speaking.”

Do those words sound familiar? If you are a bible reader they should, for they are found in The Holy Bible, The New Testament, Matthew 6: 5-8, which comprise part of what is referred to as The Sermon on the Mount, in which Jesus is giving instructions to the multitudes as to how they should pray.

Who are these people who insist on praying, not just in the “corners of the streets,” but on the steps of City Hall, and other public areas (meaning tax-payer-supported properties)? They profess to be Christians, yet seem curiously uninformed when it comes to praying according to their Lord’s instructions. Could it be that they have not read the Sermon on the Mount, or can these passages have been otherwise interpreted by their pastors? I sought some professional opinions on this matter.

A former evangelical preacher, whose intense biblical studies led him to atheism, said that many Christians don’t consider themselves to be hypocrites, or ‘like’ hypocrites, but as sincere and earnest spreaders of the gospel and prayer. Therefore, the warning of praying silently is not applicable to them.

From a Presbyterian minister, I received this reply: “As C.S. Lewis said, ‘the purpose of prayer is not to change God, but to change us.’ Unfortunately, prayer can also be a way to escape reality. People hypnotize themselves into feeling better without addressing the real problems. Prayer can also be a way one group tries to get hold of the public sphere. So in Matthew 6: 5-8, Jesus puts a warning label on prayer, ‘keep it short, keep it authentic and don’t force it on people.’ “

“Congress mandated this ‘civil religion’ event in 1952, but it has become increasingly dominated by religious broadcaster, James Dobson, and other religious right leaders who have hijacked the NDP to promote their religious political agenda,” Americans United director Barry Lynn has said. “These groups are promoting bad history, bad law and bad interfaith relations. Task force materials tell local organizers that they need not allow religions outside of the ‘Judeo Christian’ tradition to participate. They recommend that only church leaders who believe in ‘salvation by grace alone and who have personal relationships with Christ’ get access to the microphone.”

Thomas Jefferson wrote the Reverend Samuel Miller in 1808: “Fasting and prayer are religious exercises; the enjoining of them an act of discipline. Every religious society has a right to determine for itself the times of these exercises, and objects proper for their own particular tenet, and the right can never be safer than in their own hands where the Constitution has placed them.”

The First Amendment of the Constitution states that, “Congress shall make no law respecting the establishment of religion or prohibiting the free exercise thereof.” This is an important but often disputed statement. An excellent book on the background of it, and its application by the courts over the years, is titled Religion and the State, Essays in Honor of Leo Pfeffer, edited by James E. Wood, Jr., Baylor University Press. In the essay on the original meaning of the Establishment Clause, the case of Everson v. Board of Education (1947) is quoted:

“The amendment purpose was not to strike merely at the establishment of a single sect, creed or religion, outlawing only a formal relation such as had prevailed in Europe, and some of the colonies. Necessarily, it was to uproot all such relationships, but the object was broader than separating church and state in the narrow sense. It was to create a permanent separation of the spheres of religious activity and civil authority by comprehensively forbidding every form of public aid or support for religion.”

It was on June 8, 1789 that James Madison introduced the proposed Bill of Rights into the House of Representatives. Congress passed the bill in September, and it was sent to the states for ratification, a process that was completed when Virginia ratified it in 1791, thus making the Bill of Rights a permanent part of the Constitution in 1791.

Leap across the years to the Texas Bill of Rights, Article Six, which states: “Freedom in Religious worship Guaranteed—All men have a natural and indefeasible right to worship Almighty God according to the dictates of their own consciences. No man shall be compelled to attend, erect or support any place of worship, or to maintain any ministry against his consent, and no preference shall ever be given by law to any religious society or mode of worship.”

Section 7 states: “No Appropriation for Sectarian Purposes. No money shall be appropriated or drawn from the Treasury for the benefit of any religious sect or religious society, theological or religious seminary, nor shall property belonging to the State be appropriated for any such purposes.”

So what about the steps of San Antonio City Hall, for the celebration of the National Day of Prayer?

I turned again to the clergy and consulted a Catholic monsignor for his opinion on the subject of the Matthew verses on prayer. His feeling about Jesus’ instructions were that Jesus indeed meant that prayer should be quiet and in private, and that assemblages of various religious groups would certainly require that prayers be silent. He was very aware of the religious right’s efforts to intrude into politics but was not acquainted with San Antonio’s particular celebration on the steps of City Hall on National Day of Prayer, the location of which surprised him.

“That all sounds very sweet,” he said, “but with what this country has become, which is very diverse in race and religion, and our reputation being what it is worldwide, this kind of event should be thought of globally. Every religion and religious sect should be invited and, if attending, that would most certainly rule out prayers recited over a microphone by only pastors of religions approved by James Dobson and other religious right leaders.”

We get another perspective on the proper location for these public prayers when we read Justice Hugo L. Black’s statement in 1947 (the majority opinion in Everson v. Board of Education):

“The establishment of religion clause of the First Amendment means at least this: Neither a state nor the Federal Government can set up a church. Neither can pass laws which aid one religion, aid all religions, or prefer one religion over another. Neither can force nor influence a person to go to or to remain away from church against their will or force him to profess a belief, or disbelief, in any religion.”

Madison’s attitude towards the mixing of church and government was: “Experience witnesseth that ecclesiastical establishments, instead of maintaining the purity and efficacy of religion, have had a contrary operation. During almost fifteen centuries has the legal establishment of Christianity been on trial. What has been its fruits? More or less, in all places, pride and indolence in the clergy; ignorance and servility in the laity, in both, superstition, bigotry and persecution.”

Catherine Fahringer is an officer of the Freedom From Religion Foundation. This article was originally written for the San Antonio Express-News.