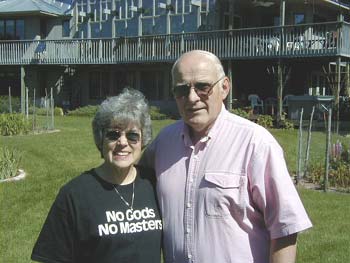

Meet Jane & Stefan Shoup

Jane and Stefan Shoup

|

Meet Jane and Stefan, members of the Freedom From Religion Foundation (Jane is a Life Member), who live in east central Wisconsin. Both retired from demanding careers, they reside in an unusual, custom-built, energy-efficient home in a rural location and lead busy lives together.

Stefan comes from a long line of freethinkers. His Scandinavian grandparents on the maternal side broke away from the narrow, circumscribed religious dogma of their relatives and friends in Henning, Minn., in the early 20th century. By WWI, such rejection of faith, as well as their support of persecuted German farmers in the area, made it unsafe to stay. Together with their three daughters, William and Annie Nelson moved to vibrant Minneapolis, which opened up a wealth of enlightenment opportunities. They quickly found the First Unitarian Society under the great secular humanist minister John Dietrich. All four of their children subsequently graduated from the University of Minnesota and remained religious liberals (all nontheists) throughout their lives. Stefan’s mother, Corelli Nelson Shoup, who will be 100 years old in August, remains an outspoken exponent of humanism and critic of dogmatic, god-centered religion.

Stefan says he was an atheist as far back as he can remember, growing up in the liberal, nontheistic Third Unitarian Church on the westside of Chicago, where “God” was never part of the belief system. In church school in the 1940s and ’50s, Stefan remembers the discussion of religious and political skeptics, dissenters, and apostates–an array of people who rejected the status quo and who spoke out for social equality and a religion responsive to the advance of science. It was a formative experience.

His mother taught in the church school, emphasizing the lives and expressions of great freethinkers and the recognition that–except for each other–we are alone and must confront and solve our own problems. A lifelong lover of poetry, she has only lately stopped giving dramatic poetry programs, including such liberal staples as Edwin Markham’s stirring paean to humanism:

“We men of earth have here the stuff

Of Paradise–we have enough!

We need no other stones to build

The stairs into the Unfulfilled.

No other ivory for the doors,

No other marble for the floors–

No other cedar for the beam

And dome of man’s immortal dream.

Here on the paths of every day

Here on the common human way

Is all the busy gods would take

To build a Heaven, to mold and make

New Edens. Ours the task sublime:

To build eternity in time!”

In his childhood and early teens, Stefan remembers celebrating Unitarian “saints” like Michael Servetus, Tom Paine, William Ellery Channing, Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Robert G. Ingersoll. It all seemed so reasonable and sane. As he puts it, “I never had to un-learn anything! That’s the beauty of not being burdened with dogma and revealed truth.”

Jane grew up in a more traditional, nominally Presbyterian home. Her mother was crippled by polio as a child and in frail health most of her short life; both parents retained their Christian beliefs. In high school, Jane began to question such beliefs, spurred on by a young atheist friend. At the University of Rochester, early in her first year, she decided to attend a Unitarian youth group meeting to find out what liberal religion was all about. It was there that she and Stefan first met. Jane was further influenced in her thinking by reading and her undergraduate major in the biological sciences. She soon came to believe that a natural explanation of life is all one needs. She continues to be inspired by Harvard biologist E.O. Wilson, speaking of his own emergence from a Southern Baptist upbringing to a greatly enlarged view of the earth:

“. . . I learned that scientific materialism explains vastly more of the tangible world, physical and biological, in precise and useful detail, than the Iron-Age theology and mysticism bequeathed us by the modern great religions ever dreamed. It offers an epic view of the origin and meaning of humanity far greater, and I believe more noble, than conceived by all the prophets of old combined. Its discoveries suggest that, like it or not, we are alone. We must measure and judge ourselves, and we will decide our own destiny.”

Jane and Stefan remain Unitarians, albeit of the secular humanist variety, and feel that a liberal society, which can embrace atheists, agnostics, as well as those with some spiritual inclination, has a lot to offer as a community rallying center for the doubters, skeptics, and the otherwise disenchanted. They are active in the Stevens Point Unitarian-Universalist Fellowship.

Stefan received undergraduate degrees in chemical engineering and English at the University of Rochester, a Masters in English at the University of Chicago, and later a Masters in Industrial Management from Purdue-Calumet. Jane graduated with a BA in Biology from Rochester and completed a PhD in zoology at Chicago.

After a 3-year stint in the Navy for Stefan, he and Jane settled for the next 32 years in Hammond, Ind. Stefan worked in research and as a pollution control engineer for Inland Steel Company, and Jane became professor of biological sciences at Purdue University-Calumet. They have raised two accomplished daughters.

Rebecca J. (Shoup) Karpoff (b. 1965) is a professional singer (BA/BMus, Northwestern, M.Mus., DMA, Eastman School of Music) and Director of Music/Office Administrator at the First Unitarian-Universalist Society of Syracuse, N.Y. Her husband, Fred Karpoff, is professor of piano at Syracuse University. Fred, who chairs the Social Concerns Committee at First UU, recounts the experiences of their young daughters in their encounters with school friends. On hearing Luella (then five) sitting on the toilet singing “Jesus Loves Me,” he determined that some antidote might be indicated. On another occasion he noticed Elena (eight) in an attitude of prayer with a playmate. She explained that she was “trying out prayer to see if it worked.” This time Luella was quick to interject, “Prayer doesn’t work. I know; I prayed for a Barbie doll and I didn’t get it!” Fred, the social activist, might have interjected at this point Robert G. Ingersoll’s injunction: “The hands that help are better far than the lips that pray.”

Jane and Stefan’s younger daughter, Rachel Shoup (b. 1968) is a cognitive psychologist/cognitive scientist (BA, Carleton, PhD, Indiana University) and lecturer at UC Berkeley and Cal State Hayward. She and her husband, Joseph Rogers (director of operations for a small mortgage services company in the Bay Area) are also atheists, who report that they frequently cite Dan Barker’s Losing Faith in Faith in lively conversation with friends. Rachel and Joe, both with science degrees and a pragmatic, disciplined approach to the mysteries of life, came to their nontheism rather easily, Rachel in her teens, and Joe a little later in the process of rejecting his Catholic upbringing. Like many Californians, they love the out-of-doors and take frequent advantage of camping, hiking, and skiing opportunities. Both also have become very creative ceramists in their spare time. They have a pet iguana, Rio (she’s an agnostic!).

A few years after their daughters had left home, Stefan and Jane purchased their present home and property in Wisconsin from close family friends and mentors, Doris and Andy Hoigard, an extraordinary couple–also Unitarians and freethinkers. They remember with affection many visits with the Hoigards in the Sun House, where discussions were never irrelevant, and musicales included a lot of Pete Seeger and the Weavers–“folk music with a message,” as Andy liked to say. Stef and Jane bought the house over a three-year period and when the contract was up in May of 1998, the Hoigards, after careful thought and considerable planning, committed suicide together. In their mid-seventies and facing uncertain health problems, they chose death with dignity and on their own terms.

The original Sun House built by the Hoigards was a passive solar envelope structure with 108 windows facing south. Stefan and Jane have since doubled the size of the house to about 3800 square feet, added two masonry stoves and active solar water heating. The house is super-insulated and has several other energy-efficient features. It stands on 150 wooded acres with frontage on the Little Wolf River at the mouth of Spaulding Creek, a pristine trout stream. With a guest house and plenty of extra beds, they always have room for visitors–and especially welcome are freethinkers!

Jane still teaches two courses for Purdue-Calumet, one by “distance-learning” (that is, e-mail) for prospective high school biology teachers and the other, with a colleague, a one-week field biology course for non-science majors on the Shoup property in Wisconsin. This very intensive class is packed with field activities, guest speakers, and discussions of major concepts like glacial geological changes, ecosystem structure and function, ecological succession and evolution, population dynamics, and biological carrying capacity.

This is the fourth year for this unusual and very popular course. Jane reports that each year it gets better. There is much challenging reading, including articles by Garrett Hardin, Aldo Leopold and Isaac Asimov. All this, along with tent-camping for a week, cooking their own meals on camp stoves, a highway trash pick-up, and hiking a five-mile stretch of the Ice Age Trail, is an eye-opening experience for industrial-area, urban students who seldom have considered such issues as threats to life-support systems, loss of biodiversity, and the colossal overall human impact on an increasingly beleaguered planet.

“We view traditional god-centered religions as largely responsible for most of the strife in the world, either directly through intolerance of others’ beliefs, or indirectly through encouraging population growth.”

The latter issue is a special cause of theirs. Jane points to our nation and the world as populated far beyond the earth’s carrying capacity, that is, its ability to sustain life indefinitely. Further growth seems assured into the future. At 6.3 billion people on the planet today, the UN demographers predict about 9.4 billion by the year 2050. The exponential J-curve of human population growth is staggering to contemplate.

“Can any rational person deny the gravity of this situation?” they ask. “Yet all we get from our politicians and particularly the current administration, in the face of the growing list of environmental, economic, and national security problems, is a myopic and self-serving adherence to growth–the great icon of Western capitalism.” Stefan likes to cite biologist Lamont Cole’s admonition, “Growth is the philosophy of the cancer cell and it soon consumes its host.”

Before three different UU congregations, Jane has given a talk entitled “Religious Roots of the Environmental Crisis,” which lays much of the blame right at the door of biblical teachings (go forth and multiply, have dominion over the land and other creatures, etc.) causing most of us to view humankind not as part of, but as apart from the intricate web of life. As further explained by historian Lynn White in an often-quoted essay published in Science in 1967:

“Our science and technology have grown out of Christian attitudes towards man’s relation to nature which are almost universally held, not only by Christians and neo-Christians, but also by those who regard themselves as post-Christians. Despite Copernicus, all the cosmos rotates around our little globe. Despite Darwin, we are not in our hearts part of the living process. We are superior to Nature, contemptuous of it, willing to use it for our slightest whim.”

Stefan has spoken to the same groups on “How the Gods Were Made,” a logical and evolutionary analysis of the god concept from animism to monotheism to cosmic monism–a story rooted in primitive ignorance and perpetuated through the ages via indoctrination by self-serving clergy. Richard Dawkins summed up this sorry history a few years ago in an article in Free Inquiry:

“Much of what people do is done in the name of God. Irishmen blow each other up in his name. Arabs blow themselves up in his name. Imams and ayatollahs oppress women in his name. Celibate popes and priests mess up people’s sex lives in his name. Jewish shohets cut live animals’ throats in his name. The achievements of religion in past history–bloody crusades, torturing inquisitions, mass-murdering conquistadors, culture-destroying missionaries, legally enforced resistance to each new piece of scientific truth until the last possible moment–are even more impressive. And what has it all been in aid of? I believe it is increasingly clear that the answer is absolutely nothing at all. There is no reason for believing that any sort of gods exist and quite good reason for believing that they do not exist and never have. It has all been a gigantic waste of time and a waste of life. It would be a joke of cosmic proportions if it weren’t so tragic.”

Devotees of the late, eminent ecologist Garrett Hardin, Jane and Stefan cite his unique and perceptive inquiries into the ecological basis of the human predicament. Hardin fearlessly challenged comfortable and cherished beliefs at every turn, they point out. His three “filters against [acts of] folly” include first that we must be literate–able to understand and express ourselves coherently in words. Second, we must be numerate–that is, especially in this technological/digital world, able to compile and analyze numbers through graphs, tables, and statistics so that we are not misled or beguiled by those merely verbally eloquent. Finally, we must be “ecolate” (Hardin’s term)–that is, we must have a thorough understanding of the fundamental structure and function of ecosystems–the intricate, delicate web of life on which we all depend.

“This third prescription is essential to our very survival. Recognizing that ‘we can never do merely one thing,’ we must, at the prospect of any economic, social, political, or environmental action, ask the central question, ‘. . . And then what?’ We deal in palliatives and poultices, not in the hard, rational decision-making which seeks to identify root causes.”

Hardin says, “Whatever else a religion may be, most long-surviving religions call for a commitment that discourages the asking of questions.” In this sense, traditional monotheistic religions have debilitated us and prevented us from confronting the monumental survival problems we now face. Hardin’s disciplined and relentless approach is the only way to avoid in the future making the myriad mistakes we have heretofore made in “managing” our existence.

Another seminal idea with which Hardin startles us, Jane adds, is the simple observation that in the face of shortages of, for example, highways, food, fresh water, fish, etc., which are continually decried in the media, the fact is that there is not a shortage of this or that, but a longage of demand (i.e., excess population). We have exceeded the limits.

Jane and Stefan feel that Hardin and others, including Lester Brown, Richard Dawkins, and Daniel Quinn, are “required reading.” Hardin’s essay “The Tragedy of the Commons” (1968) is a classic. His Living Within Limits (1993) is a fine summary of his life’s work and a real wake-up call, as are Lester Brown’s two recent books, Eco-Economy: Building an Economy for the Earth (2001), and Plan B–Rescuing a Planet Under Stress and a Civilization in Trouble (2003). Like Rachel Carson’s ground-breaking Silent Spring (1962), these books need the widest readership. Richard Dawkins, that most insightful freethinker and acclaimed biologist, has many thoughtful books, including The Blind Watchmaker (1986), The Selfish Gene (1989), and River Out of Eden (1995). Finally, Jane particularly recommends Daniel Quinn’s Ishmael (1992) and The Story of B (1996) as two provocative parables for our time.

Jane and Stefan’s other interests are varied. Jane is becoming a proficient weaver in retirement, selling her scarves, shawls, and placemats at local craft fairs and on commission. Together, the Shoups show their solar home twice each year for the Midwest Renewable Energy Association fairs.

They are avid gardeners, harvesting and putting up most of their year’s supply of vegetables and fruits. Recently they planted four acres in red pines and a one-acre plot in tall grass prairie on their property. Jane buys whole berries and grinds them into flour for bread, baking a delicious rye bread.

“We grow and put up almost all of our vegetables (spinach, carrots, beets, cabbage, tomatoes, summer and winter squash, potatoes, asparagus, turnips, parsnips, cauliflower, broccoli, Brussel sprouts), and a few fruits (apples, blueberries, raspberries, and rhubarb).We don’t hunt, but our neighbor hunts our land and we eat a lot of venison throughout the year.”

They are also active in efforts to preserve the Upper Little Wolf Watershed through membership in the Northeast Wisconsin Land Trust, and are part of a team of volunteers who are monitoring the Little Wolf River tributary streams for water quality.

The Shoups participate in the Learning Is For Ever (LIFE) program through the University of Wisconsin-Stevens Point. Jane has presented one short course on “Evolution and Ecology” and this fall, together, they will conduct a discussion on Garrett Hardin’s lengthy article, “An Ecolate View of the Human Predicament.”

With two high-efficiency masonry stoves and a conventional wood stove, Stefan is preoccupied with procuring fuel. Although the Shoups rely primarily on passive solar energy for heat, on cold, cloudy days they turn to wood-burning. Stefan says that splitting wood, while arduous, is a tonic. It gives one time to “mellow out” and to think. In its fundamental essence it can be a kind of experience that feeds the spirit. As Archibald MacLeish once observed, “When I die, I would like to go splitting wood!”

Stefan and Jane agree it isn’t hard to stay busy. There is much to do, and so much to read, including Freethought Today. They hope that we as a species can see our way, through sane, rational thought, to leave behind us, in the words of the late Nobel Laureate biologist George Wald, “a better world for fewer children.”