By Ken Lynn

Each day in America’s public and parochial schools, teachers and over 60 million students recite the Pledge of Allegiance along with thousands of citizens at meetings of the Boy Scouts, Girl Scouts, American Legion and many other fraternal and patriotic organizations. Most do so having no idea of the origin or meaning of the Pledge. The United States is one of the few nations in the world to have a pledge to its flag. How has this Pledge of Allegiance to our flag usurped the U.S. Constitution and Bill of Rights as the cornerstone of American patriotism?

The Pledge was first published in the September 8, 1892 issue of Youth’s Companion, a weekly family magazine published by the Perry Mason Company in Boston. With a circulation of over 500,000, the Companion had the largest national circulation of its day. Daniel Ford owned Youth’s Companion, and his nephew-by-marriage, James B. Upham, was a key staff member and a junior partner in the Perry Mason Company.

In 1891, Francis Bellamy, a Christian Socialist and Baptist minister, joined the staff of Youth’s Companion. Bellamy was first cousin of Edward Bellamy, author of the widely circulated socialist utopian novel Looking Backward 2000-1887. Written in 1888, this book, which sold over a million copies in its first few years, described a future America completely socialized with all economic activity carefully planned. As Vice-President of the Society of Christian Socialists, Francis Bellamy lectured and preached on the virtues of socialism, giving a speech entitled “Jesus the Socialist,” and a series of sermons on “The Socialism of the Primitive Church.” In 1891, he was forced to resign from his Boston church because of his socialist views and activities.

Seeking ideas to commemorate the 400th anniversary of the discovery of America on Columbus Day, 1892, President Benjamin Harrison had initiated a call for the development of a special patriotic school program to highlight the event. Bellamy and Upham were able to line up the National Education Association to support Youth’s Companion as a sponsor of the observance, and arranged for President Harrison and Congress to announce a national proclamation which centered around an American flag ceremony and (then unwritten) flag salute.

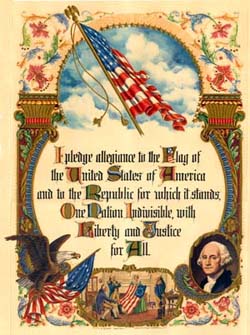

Bellamy, under the supervision of Upham, then authored the program for the celebration, including the flag salute or Pledge of Allegiance. His original version was, “I pledge allegiance to my flag and to the Republic for which it stands, one nation, indivisible, with liberty and justice for all.” Bellamy considered putting the words “fraternity” and “equality” into the Pledge, but decided against it as equality for blacks and women was a controversial rather than patriotic issue of the time. Originally intended for recitation on that single day, the Pledge was an instant success and was quickly adopted by the nation.

The Pledge remained in its original version until 1923 when the words “my flag” were changed to “the Flag of the United States” at the urging of the American Legion’s National Flag Conference. The following year the Pledge was altered again with the addition “of America” after “Flag of the United States.” This version of the Pledge was codified into Public Law in 1942.

The Pledge remained unchanged until the paranoia and hysteria stemming from Sen. Joseph R. McCarthy’s “red scare” hearings swept the nation in the 1950s. Fearing Communism might cross the Atlantic and engulf America, a feeling arose in Congress and throughout parts of the nation that by acknowledging “God” as our national symbol, America would be protected from the Communist menace. Scoring a religious Trifecta of sorts, the Pledge was amended in 1954 to include the words “under God;” legislation to add the motto “In God We Trust” to all coins and currency was passed in 1955; and the national motto “E Pluribus Unum” [out of many, one] was changed to “In God We Trust” in 1956. Collectively these measures form an interesting trilogy of laws for a country founded on a secular Constitution and a belief in the separation of church and state.

Since 1954, the now religious Pledge has read: “I pledge allegiance to the Flag of the United States of America, and to the Republic for which it stands, one Nation under God, indivisible, with liberty and justice for all.” In an attempt to mitigate the effects of this controversial change, some religionists claim that the words “under God” merely declare the right of the people to express their belief in a God, not that the nation itself was founded on a belief in a God. Unfortunately, a look at the historical record indicates the latter is exactly what Congress intended when it inserted “under God” into the Pledge.

The resolution to change the Pledge was introduced into the House by Rep. Louis C. Rabaut. He proposed to add the words “under God” as “one nation, under God.” Note the placement of the comma between “one nation” and “under God.” As part of its deliberations, the House Judiciary Committee solicited an opinion for comma placement from the Library of Congress. Three proposals were considered:

- one Nation, under God

- one Nation under God

- one Nation indivisible under God

The Library of Congress reported the following recommendation:

“. . . Under the generally accepted rules of grammar, a modifier should normally be placed as close as possible to the word it modifies. In the present instance, this would indicate that the phrase ‘under God,’ being intended as a fundamental and basic characterization of our Nation, might well be put immediately following the word ‘Nation.’ Further, since the basic idea is a Nation founded on a belief in God, there would seem to be no reason for a comma after Nation; ‘one Nation under God’ thus becomes a single phrase, emphasizing precisely the idea desired by the authors . . .”

The Judiciary Committee and the House concurred with the Library of Congress, adopting the single phrase. The Senate co-sponsor of the resolution was Sen. Homer Ferguson, who said of the joint resolution during Senate debate, “Our Nation was founded on a fundamental belief in God . . .” Evidently, it was so important for this Congress to officially acknowledge the United States as a nation founded on a belief in a God, that even comma placement was debated to ensure the proper meaning was conveyed! With insertion of the words “under God,” the Pledge has now become both a patriotic oath and a public prayer.

When we pledge allegiance, what are we doing? According to Black’s Law Dictionary, 6th edition, allegiance is defined as: “Obligation of fidelity and obedience to government in consideration for protection that government gives.” Although the flag represents the embodiment of our national conscience and is easily the most recognized symbol of our nation, one that I proudly support and defend daily as a member of our nation’s Armed Forces, I find it curious that a “religious” Pledge of Allegiance to our flag rather than a Pledge of Allegiance to our secular Constitution has become the institutionalized form of patriotism in our country.

Members of the military are required to swear or affirm their support and defense of the Constitution of the United States. I have gladly “pledged my allegiance” by making this affirmation, and I, like many other atheists in foxholes, would give my life if necessary to defend our Constitution and our great democratic way of life.

Ken Lynn is an active duty Air Force officer currently stationed in Alabama. He and his wife Monica are Foundation members.