It’s probably been almost 35 years since I’ve had a chance to speak to an audience like this. Then it was the congregation of my church. Today it’s a slightly different group–but I feel very much at home here.

Dan Barker asked me a year or so ago to sit down and write a piece about how I got here, from being a Catholic priest to a member of your group, the Freedom From Religion Foundation. How did I come out of such a religious family and the environment of the deep South to be a freethinker? I put it off because I wasn’t sure how I “got here,” so this opportunity to speak to you today came as a challenge.

Thinking about this talk, I called my daughter–who’s in law school–and asked her if she had ever known me as a believer. She said, “Dad, I suspect that you never were a believer.” I wondered if she was right, and I began to reflect on my Catholic childhood.

I was raised by a Roman Catholic mother who was Irish-French and by a Presbyterian father, in a small Southern town–Natchez, on the banks of the Mississippi River, 70 miles south of Vicksburg. All of our priests were Irishmen, very moralistic and authoritarian. Growing up Catholic in the ’40s and the ’50s meant never, ever having to confront the fact that you were a believer in a god. You were exposed to a society, a church in which you were baptized in infancy. You were confirmed when you could hardly walk, and there was never a discussion about god and spirits for individuals. We never had to make a statement as our Protestant friends did, where they would announce their trust in Jesus or be “born again.” Catholicism was a given. It was simply who I was, something almost like my ethnic origin. Did I really believe in God? Was I ever asked if I believed in God? No.

Early this morning I read a column in our Capital Times in which the author talked about taking the train to Dallas in November of 1963 and being at the scene where Lee Harvey Oswald assassinated John Kennedy. At four o’clock this morning I could remember with total recall where I was, what I was thinking, what everything was like on that day 38 years ago. I can remember those details more strongly than I remember last September 11th or anything about my mother’s death or numerous other important events in my life. This morning I kept wondering: Why do I remember Kennedy’s death so clearly and why did it mean so much to me? I realized that his death and how much it mattered to me is all tied up with my trip from being a priest to being an atheist.

I started school in a Catholic kindergarten when I was four years old. In November of 1963, when Kennedy was murdered, I was 25 and in my last year of Roman Catholic seminary, waiting to be ordained in nine months as a priest. I had spent the summer of 1963 doing extraordinary things, especially for me as a Southern white boy. On a very hot day in August of 1963, wearing my priest collar, I attended the March on Washington and heard Martin Luther King give his famous speech. I wasn’t supposed to be in Washington. My bishop had told seminarians not to go near Washington that weekend. My parents told me that I was not to go near Washington. But I felt enthralled by King.

I had been resentful of President Kennedy, who up until then had not been very supportive of what was going on in the civil rights movement. But not long after King’s speech my view of Kennedy began to change. The president gave some remarkable speeches that summer and became a man who was willing to stand up and be counted. Something happened to me. I began to see Kennedy as the person who could change society. I wanted to be part of the coming struggle in Mississippi, to be a leader in the battle to combat racism.

But my father was giving me holy hell about my involvement. He told me I should get out of the seminary and go into social work. He said, “That’s what you really want to do.” Well, I had been in seminary for nearly nine years, and I was determined to be ordained and make a difference. What I could still believe, in the early ’60s in the seminary, was that this God, this church, this thing was on the move. And just this morning I realized that the day Kennedy was killed was the day I began to lose my faith and become an atheist. I thought: If God will let Kennedy be murdered, whose side is he on? Or does he even care? Is he really listening? Is there even a God?

So Kennedy’s death was the beginning of the end for me, and the murder of my hero Martin Luther King five years later was the end of the end. It was a slow progression in my heart and soul, as I came to grips with the fact that I needed to move on and to get out of the Catholic Church. It was extremely hard, extremely scary. I’d been in the seminary for 14 years. I’d been a priest for five years, and I’d been considered Roman Catholic for all my life–31, 32 years. To get out of that, and to tell my family that I was leaving, was very hard. I was also very close to a group of young seminarians. Among them, perhaps the closest friend I had back then was a young priest named Bernie Law, who is today the Cardinal Archbishop of Boston. To tell these priest buddies of mine was also very hard.

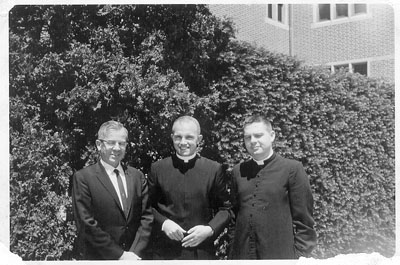

Tom (center) with his dad (left) and young Bernard Law (right), who is now “notorious” Cardinal Law of Boston

Incidentally, most of these buddies are no longer priests today. Some are dead; others quit the priesthood. Even Bernie Law sort of quit the priesthood too–to become an Ecclesiastic! [audience laughter] But most of them who survive are still religious and still go to church. They look at me today and say, “What went wrong? How could you give up on your culture, your background, your heritage?”

Once I did quit the priesthood, I found myself here in Madison, Wisconsin, studying social work, still trying to be Catholic and fascinated with this new town. I could walk around without a collar, by god! Nobody knew who I was. They still heard the Southern accent, but this was a big town and I felt invisible and I fell in love with it. I was only going to be here two years, and that was 32 years ago. I’m still here.

My story is still evolving. I hope it’s an incentive for others to ask a lot of questions! I’ve totally skipped one subject that’s central to Catholicism and the priesthood, and that’s celibacy [audience laughter]. How did I get to be celibate, how did that happen? Well, more interesting is how did I get out of being celibate? [audience laughter]

As you can imagine, at age 32 I was still a virgin physically. I got married and have stayed married to my wife Judy ever since, although I’ve given her holy hell. Early on, when we were struggling in our marriage, we went to a psychiatrist, and he asked us, “Have either of you been married before?” And I said, “No, but I used to be a priest.” He said, “You were married to Holy Mother and the Church.”

Question: How did your family and church authorities react to your leaving the priesthood?

Both of my parents were very religious, but both were very angry that I went to the seminary. Somewhat of a conundrum. I pleased them, I thought, by being very religious as they had taught me. But they sort of said, “We didn’t want you to be that religious.” [audience laughter] I think they were thinking grandchildren, and you know, going to church every now and then, and here I was going all the way.

When I left the priesthood, my mother had already died and my father was only slightly disappointed (though he had converted to Catholicism). But when he came to see me here in Madison and couldn’t find a crucifix or a bible in the house, he realized I didn’t go to church. That really disappointed him.

Did the church authorities try to talk me out of it? To the contrary, I was outspoken and pretty honest and they were probably relieved to see me go. I had come to realize, while still a priest, that I didn’t believe in God. I was using the bully pulpit I had as a priest to be a teacher, to push the organization to change. What broke my back morally was a document called Humanae Vitae, issued in 1968, one month after Martin Luther King was killed. It said the only form of birth control that could be used was the age-old rhythm method. For me, such a decision was stunning since for years a committee of clergy and laypeople was saying we’ve got to change our birth control policy. So, to have the Pope go the opposite way and turn against it, just snapped the last thread of my interest in hanging around the priesthood.

The news about Vatican II had been concealed from us in the seminary since we were not allowed to watch television or allowed to read about it. Vatican II sort of held us there because we thought a revolution was coming. We guessed wrong.

Question: Was there any other doctrinal issues besides birth control and atheism that you had major fights with and disagreements?

Let me tell you a little about life in the seminary. In the Josephinum (Pontifical College Josephinum in Worthington, Ohio), and in most seminaries in the ’50s and ’60s, we were taught by people who had grown up 40 years before us. Many lectures were in Latin. I could read Latin and can today, but I couldn’t understand a word of it.

We used to sit in class and read what were then radical German and French theologians with the textbook covers torn off. What I got out of the seminary, in 1964, was that I wasn’t a theologian. I was there to be an instrument of God, or an instrument of something, on the race issue. And that was the major thing that I wanted to do, that I tried to do, and I did it incessantly.

Once you question one thing, such as birth control, and begin to say “This could not be true,” it was like a whole house of cards falling down. I remember thinking, “That means papal infallibility is not true.” Papal infallibility was only declared in 1870. How did that happen? It was a grievous, arrogant mistake that the Catholics made. I remember getting up at a meeting of priests and saying, “This could not be true. We made a mistake.”

In the world I lived in, the priests were the foot soldiers, not the theologians.

Question: Did you work in a parish?

I was assigned to the white Catholic Church. I knew a lot about the Vatican Council but–and this is a touchy subject–the one area I knew very little about was sex. All I knew was out of a book. Sexuality as a child in my world had been awfully handled. As a priest I was open about talking to my young charges about masturbation, about sexual feelings, and I helped them come to grips with what it’s like to be a human being and accept these things in you. It got me into a lot of trouble. [audience laughter] I think people saw me as somewhat of a rebel. But I was very isolated.

Question: You mentioned your daughter and that she thinks perhaps you never had been a believer, and I’m wondering as she was growing up, what did you use for spiritual guidance? Was there any religion of any kind?

My wife is still a Christian, goes to church, and the two kids were baptized and completed confirmation classes at First Congregationalist Church here in town. But at least right now, I’ve sort of won them over. But I’m not sure. The question was what kind of spiritual thinking did I give my children? I personally probably did not give them “spiritual guidance” since I was very negative and resentful of all organized religion. They knew when they were children that their mother and I differed on this topic.

Question: When you left the priesthood, what did you do?

I intended to get a degree in psychology. I wanted to be a psychologist, because I was always told I was a good listener. But to be a psychologist would have taken four years of undergraduate work and then many more years to get a Ph.D. So I said, “Well, what else can I do?” They said, “Have you ever heard of social work?” I was handed a pamphlet from a university up north. And I fell in love with it, just with that pamphlet.

Here’s the funny part. I got the pamphlet in a little clinic in a community in Mississippi called Mound Bayou, an all-black community. Tufts University had an outreach center there. I’m sure these pamphlets were sent down by Madison’s school and were coded, because when I walked in the door at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, they looked up and said, “Oh, you’re white!”

I persevered. I worked with Dane County Human Services for almost 30 years, and was a social work supervisor in child abuse and juvenile court work. I retired three years ago and am now looking for a new career.

Question: Some years ago I heard the expression from a priest and a friend of his, that they’d both taken the “Cardinal’s oath.” This meant that even in the face of saying something that they probably did not believe, as opposed to their own beliefs, they would go ahead and say what the Church wanted them to say. Have you ever heard the expression?

No, I haven’t heard the expression. But it rings true. I remember the night before I was ordained, the bishop was the Apostolic delegate from Washington and he said, “No matter what your bishop tells you to do, do it.” I remember just sitting there and thinking, “I’m not going to do that.”

Another funny story: a week earlier, before the ordination: we’d been on a week’s retreat in silence, right up the street from Ohio State University along the banks of the Allegheny. Being on a retreat back in those days was a week of silence, walking and meditation. The monsignor came to me the night before ordination and said, “I really had to fight to get you ordained because a priest started following you around during retreat, and he noticed that you were skipping rocks across the river, and looking up at the sky and at the trees and throwing berries and things.” [audience laughter] I was 26 years old. That was me. But the Cardinal’s oath, I would have laughed at that.

Catholicism has become a much more conservative organization than when I was in seminary. Of 15 priests in my class, 12 have left the priesthood. Pedophilia is a major problem that is sweeping the church. They’ve been trying to muzzle any information about its happening but it’s causing the priesthood to be destroyed.

A good friend of mine said, “Gee, I wish we had married priests so we could keep you in the priesthood.” And I said, “Well, the fact that I’m an atheist might get in the way, too.” But he said, “I hope we have a married priesthood.” I hope we never do, because the church is so rotten and so politically corrupt, that by allowing priests to marry you’ll only postpone the inevitable–[applause]–of laypeople, real people, taking over and slowly doing away with this Old Testament invention of the priesthood.

Question: How did your racial sensitivity develop?

I was raised in a totally segregated world and went into seminary in 1955. I was 17 years old. In 1957 I remember two things happened: Little Rock–those of you in my age bracket remember that federal courts ordered Central High School to be integrated and the federal government sent in troops. And second, there was a debate in my class, and I volunteered to take the side of Orville Faubus, the segregationist governor. I remember writing that races were not meant to mix. I had all sorts of stuff in my head.

About six months later, Xavier, the bishop of New Orleans, Joseph Rummel, issued a bishop’s letter saying racial segregation was immoral. Imagine if I came in here and told you there is no wall behind me, there is no one sitting on this platform, there are no lights over your head. That’s how it hit me. I was incredibly suppressed and biased. We’d never talked about this. I sat from age 4 to 17 in Catholic schools, and race relations were never discussed.

I remember it just opened me up. I didn’t walk away from it, because I was a loyal person at the time. If the bishop said it, then it must be true. And slowly, as I went into seminary in Ohio, I started going Zto school with African American seminarians and the blinders dropped from my eyes. In my short lifetime, I had gone from hearing my grandmother tell about her memories as a person only one generation removed from being a slave-owner to my becoming an advocate of civil rights for all. It was a strange journey. I should add that Bernie Law was a positive influence for me on this issue.

Question: What is your view of one of the most respected humans, the Pope?

I have to stop and think. Who is the Pope? I think he is a very conservative man. When he became pope he put the kibosh on everything. And he’s much more conservative than the previous pope. But I think he’s perhaps the first pope that I see through a freethinker’s eyes. To me, personally, he’s irrelevant.

Comment: I’m glad that the Ecumenical movement did not create a Protestant-Catholic church. It would have been more difficult for you to go away.

I totally agree with that, it’s a good thing it didn’t happen. The second comment was about race–he said look at the color of this room, of this convention. I grew up in the South where religion was very much a lifesaver to African Americans. Given all that, African Americans in the South tend to be very religious. When I’ve told my few black friends in Madison that I’m a nonbeliever, they’re just incredulous.

Question: Were you aware of the cover-up of pedophilia?

I was first aware of it in the seminary. One of the teaching priests had created a cult around himself that he was somehow God’s agent, and he was sexually abusing a number of boys. When he was dismissed from the seminary, his abuse was never reported to the police. This was around 1962 and he was sent back to Rockford, Illinois, his home diocese, while all of the boys, the victims of this crime, were dismissed from the seminary.

In my years as a priest, which were only five, I heard about pedophilia one time. But I’m not at all surprised at what’s happening today. I think it’s mostly caused by the quality of people that they had to start recruiting and the anti-sexual attitudes of the Church. There were so few young men coming into the priesthood that they had to lower the standards. The screening must have been awful. Now they’re reaping the results of their recruiting efforts and have already paid millions and millions of dollars in pedophilia cases. The money is what’s getting their attention, not the damage they did to the children.

Thank you very much.